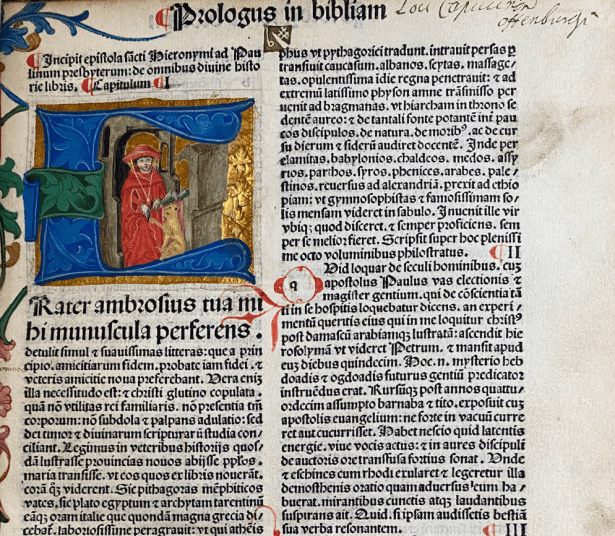

The Latin Bible is more than just another translation of the Christian Scriptures. As the standard text in use among Western Christians for more than a millennium, it came to permeate every aspect of Europe’s philosophies and theologies, literary and artistic cultures, music, warfare, and even architecture and statecraft. Such sweeping influence would have been hard to imagine in the fourth century when Jerome of Stridon, later St. Jerome, first sat down to work on a new Latin translation of the Bible using Hebrew and Greek manuscripts. Although his work had its early detractors, Jerome’s translation was soon adopted across Europe and eventually came to be known simply as the Biblia Vulgata or common Bible. As an accomplished scholar proficient in the all three biblical languages — Latin, Greek, and Hebrew — Jerome’s reputation enjoyed a powerful resurgence during the Renaissance. And yet humanist scholars, however much they admired Jerome’s erudition, believed that the Vulgate itself had become corrupted over centuries of copying and recopying. In an attempt to correct it and recover the original text, they like Jerome referred back to Greek and Hebrew exemplars. Unlike Jerome, however, the manuscripts that they had at their disposal were of a much later date with textual corruptions of their own. It is for this reason that the Latin Bible, as an ancient translation of the Bible based on the original languages, continues to be carefully consulted by biblical scholars and translators working even today.

The Latin Bible is more than just another translation of the Christian Scriptures. As the standard text in use among Western Christians for more than a millennium, it came to permeate every aspect of Europe’s philosophies and theologies, literary and artistic cultures, music, warfare, and even architecture and statecraft. Such sweeping influence would have been hard to imagine in the fourth century when Jerome of Stridon, later St. Jerome, first sat down to work on a new Latin translation of the Bible using Hebrew and Greek manuscripts. Although his work had its early detractors, Jerome’s translation was soon adopted across Europe and eventually came to be known simply as the Biblia Vulgata or common Bible. As an accomplished scholar proficient in the all three biblical languages — Latin, Greek, and Hebrew — Jerome’s reputation enjoyed a powerful resurgence during the Renaissance. And yet humanist scholars, however much they admired Jerome’s erudition, believed that the Vulgate itself had become corrupted over centuries of copying and recopying. In an attempt to correct it and recover the original text, they like Jerome referred back to Greek and Hebrew exemplars. Unlike Jerome, however, the manuscripts that they had at their disposal were of a much later date with textual corruptions of their own. It is for this reason that the Latin Bible, as an ancient translation of the Bible based on the original languages, continues to be carefully consulted by biblical scholars and translators working even today.

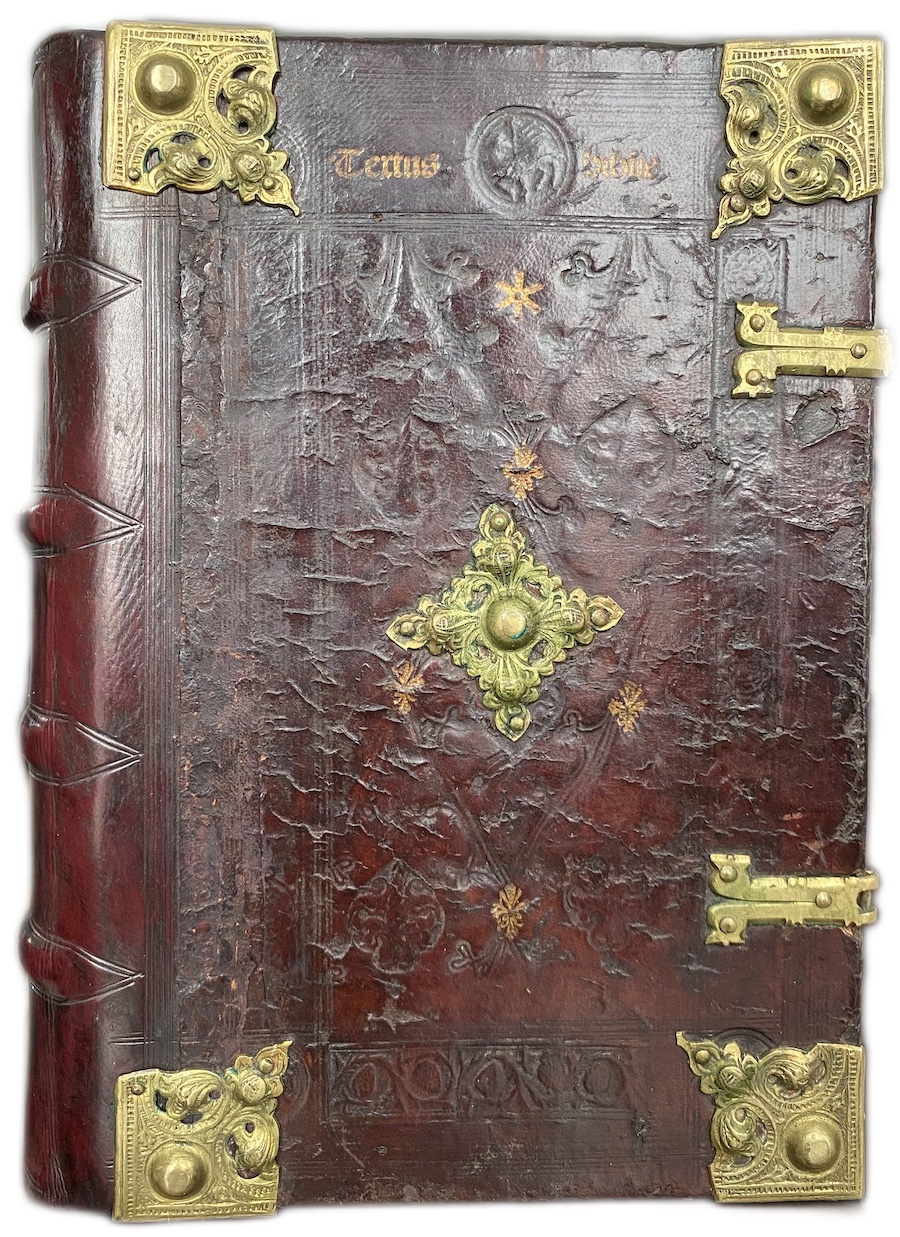

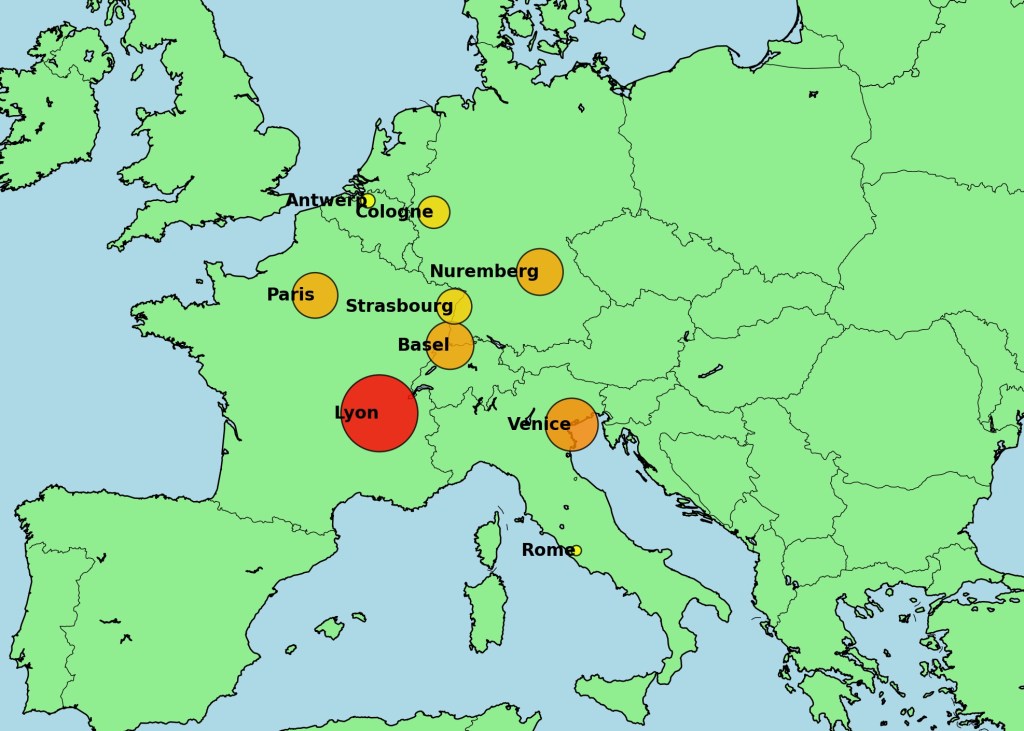

Between the first appearance of Johann Gutenberg’s Biblia Latina and the dawn of the Reformation more than half a century later, Europe witnessed technological, religious, and cultural changes that would have been inconceivable just a century earlier. As Europe transitioned from the world-altering fall of Constantinople to the defiant stance of Luther at the Diet of Worms, the continent seemed to resonate with wars and rumours of wars. The tug of powers over the Italian states, the echoing end of the Reconquista, the ominous shadow of the Inquisition, and the revelation of new and unimaginably vast territories an ocean away — all seemed like harbingers of even greater upheavals to come. During these tumultuous years, between 1455 and 1529, 171 separate editions, printed and sold by some 75 different printers, publishers, and bookellers, of the complete Latin Bible (that is, bibles that include both the Old and New Testaments) appeared in Europe. Among these the majority were large folios — an impressive format befitting Christendom’s only sacred book. As the decades passed, however, smaller and less expensive bibles — first quartos, then octavos, and even sextodecimos — began to appear with growing frequency. This was accompanied by a significant increase in the number of bibles printed with extensive woodcut illustrations as well as biblical commentaries. Not surprisingly, most of the earliest bibles were printed in Mainz, Basel, Strasbourg, and Venice. As the sixteenth century progressed, however, Lyon became the undisputed centre for the production of Latin bibles: second only to Paris as a key commercial hub in France, Lyon was home to some of the era’s most prolific printers and publishers including Jacques Sacon (a close associate of Anton Koberger), Jacques Mareschal, and Etienne Gueynard.

Despite their undisputed importance, there is no single authoritative bibliography of these early Latin bibles. This site is an attempt to fill that gap.

This bibliography includes only complete bibles printed in Latin. It does not include separately printed New Testaments (not even Erasmus), psalters, summaries, abridged bibles, parts of bibles, paupers’ bibles (biblia pauperem), or other similar works. Please note that Bod-Inc refers to the holdings in the Bodleian Library at Oxford University. D&M refers to the Historical Catalogue of the Printed Editions of Holy Scripture in the Library of the British and Foreign Bible Society compiled by T.H. Darlow and H.F. Moule (volume II/2: Polyglots and Languages other than English: Grebo to Opa).

❧ Further Reading

- The Oxford Handbook of the Latin Bible, edited by H. A. G. Houghton, Oxford: Oxford UP, 2023.

- The Vulgate Bible, edited by Swift Edgar and Angela Kinney, Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library, Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2010-2013. 6 vols.

- Paul Needham, “Fifteenth-century Latin Bible printing and distribution,” Lyell Lectures, Bodleian Libraries, Oxford University, 2021.

- Frans van Liere, “The Latin Bible c.900 to the Council of Trent, 1546” in Richard Marsden and E. Anne Matter (eds.), The New Cambridge History of the Bible, vol. 2: 600–1450 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2012): 93-109.

- Bruce Gordon and Euan Cameron, “Latin Bibles in the Early Modern Period”, in Euan Cameron (ed.), The New Cambridge History of the Bible, vol. 3: From 1450 to 1750 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016): 187-216.

- Donatien de Bruyne, Pierre-Maurice Bogaert, and Thomas O’Loughlin. Prefaces to the Latin Bible. Turnhout: Brepols, 2015.