❧ Anton Koberger and

the Postillae Woodcuts

In addition to being the most prolific publisher of Latin bibles before 1530, Anton Koberger is also responsible for producing the first Latin Bible to include woodcut illustrations. In 1485, Koberger completed a large format (Royal Folio) four-volume edition of the Latin Bible that included the commentaries, or Postillae, of Nicholas of Lyra (no. 63). Unlike earlier four-volume printed editions of the Latin Bible with Lyra’s commentaries, such as those produced by Venetian printers Nicholas Jenson and Franscicus Renner in 1481 and 1482-83 respectively (nos. 49 and 52), Koberger’s 1485 edition included 38 separate woodcut illustrations (17 of which appeared in the first volume alone).

In addition to being the most prolific publisher of Latin bibles before 1530, Anton Koberger is also responsible for producing the first Latin Bible to include woodcut illustrations. In 1485, Koberger completed a large format (Royal Folio) four-volume edition of the Latin Bible that included the commentaries, or Postillae, of Nicholas of Lyra (no. 63). Unlike earlier four-volume printed editions of the Latin Bible with Lyra’s commentaries, such as those produced by Venetian printers Nicholas Jenson and Franscicus Renner in 1481 and 1482-83 respectively (nos. 49 and 52), Koberger’s 1485 edition included 38 separate woodcut illustrations (17 of which appeared in the first volume alone).

These woodcuts were not, however, originally prepared for this edition of the Bible. Four years earlier, in 1481, Koberger had published a separate two-volume illustrated edition of Lyra’s Postillae (without the biblical text) for which he had specifically commissioned these woodcuts (in this case there were 43 woodcuts, 8 of them full-page). Koberger well knew that, before the invention of printing, it was common for manuscript copies of Lyra’s Postillae to include illustrations and he was likely attempting to conform to that tradition. Even the Jenson and Renner editions, though they did not contain any woodcuts, did contain a number of blank spaces where illustrations could (and probably in some cases were) added by hand later. At the same time, Koberger had already proven over and over that Latin bibles did not need illustrations to be commercially successful when he published unillustrated single-volume Latin bibles in 1475 (no. 18), 1477 (no. 29), 1478 (nos. 32 and 35), 1479 (no. 39), and 1480 (no. 47).

It is interesting to note that soon after completing his first illustrated edition of Lyra’s Postillae, Koberger commissioned 109 new woodcuts for a lavishly illustrated German bible he published in 1483. The fact that Koberger never felt the need to commission woodcuts for any of his Latin bibles, or to publish even a single edition of the Bible in Latin using these new biblical woodcuts, suggests a conviction on his part that those who purchased single-volume Latin bibles were not interested in illustrations. Instead, and despite having these newer biblical woodcuts at his disposal, Koberger simply reused his 1481 Postillae woodcuts in three subsequent four-volume editions of the Latin Bible featuring Lyra’s commentaries in 1486-87 (no. 63), 1493 (no. 82), and 1497 (no. 90).

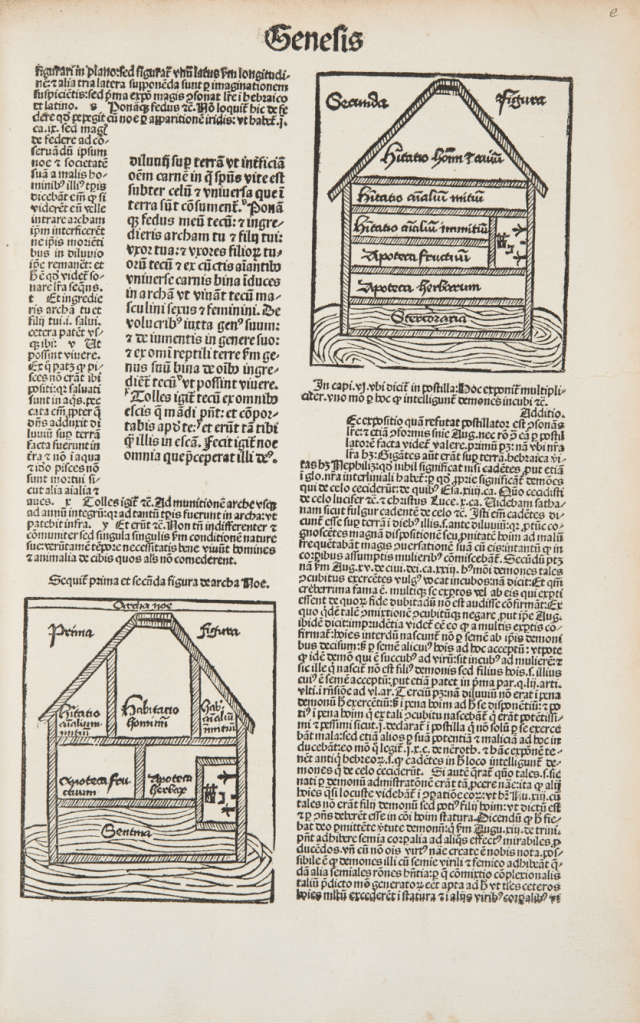

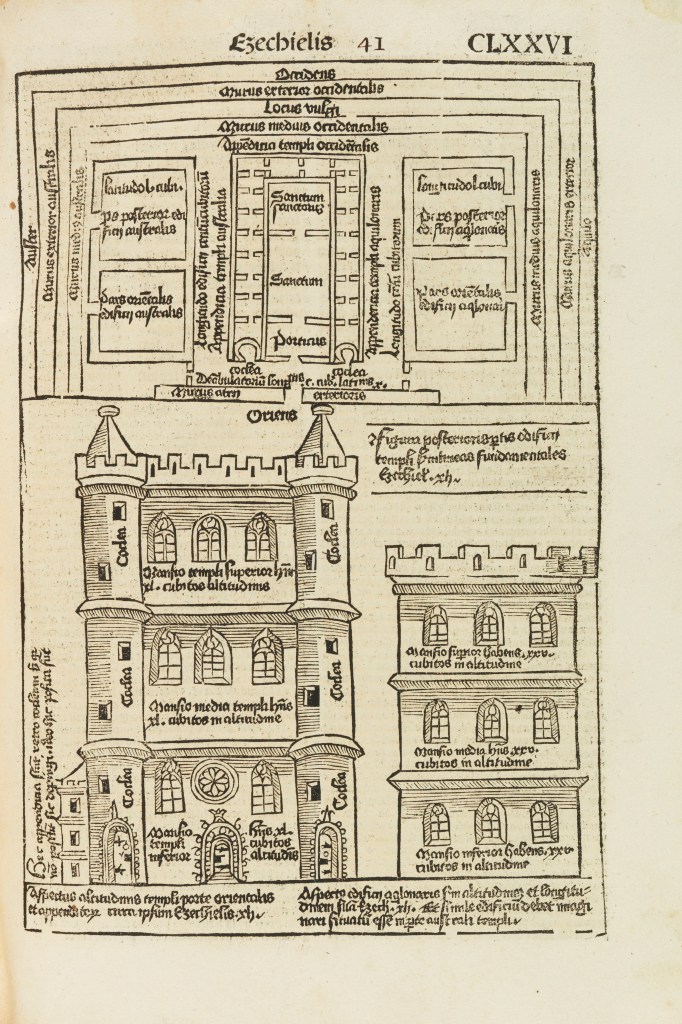

Left: Cut-away, Noah’s Ark, Biblia, Koberger, 1485. Right: Ezekiel’s Third Temple, Biblia, Koberger, 1487.

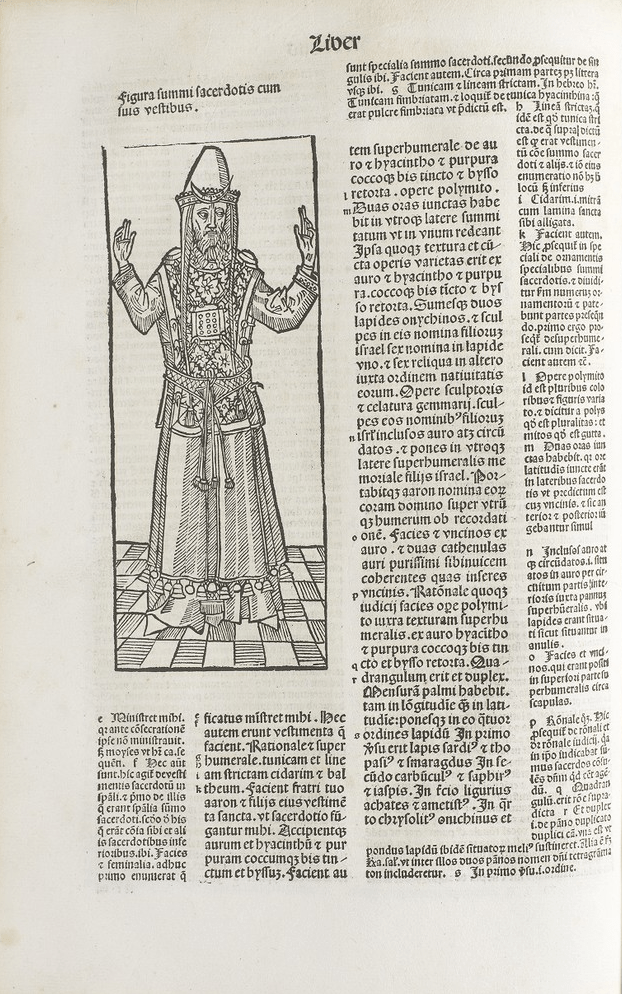

Although Koberger’s Postillae illustrations were groundbreaking when they first appeared in the early 1480s, the images themselves are largely diagrammatic in nature. They mostly depict topographies, buildings, mythological figures, and objects. One of the few human figures represented, Moses’s assistant Aaron, is clearly included for the sole purpose of depicting the complexities of his High Priestly vestments (below left). Thus these four Koberger bibles, particularly in view of the fact that the woodcuts they contain were intended to illustrate Lyra’s Postillae rather than the biblical text directly, might be said with some justification to constitute Latin bibles with illustrations rather than truly illustrated Latin bibles.

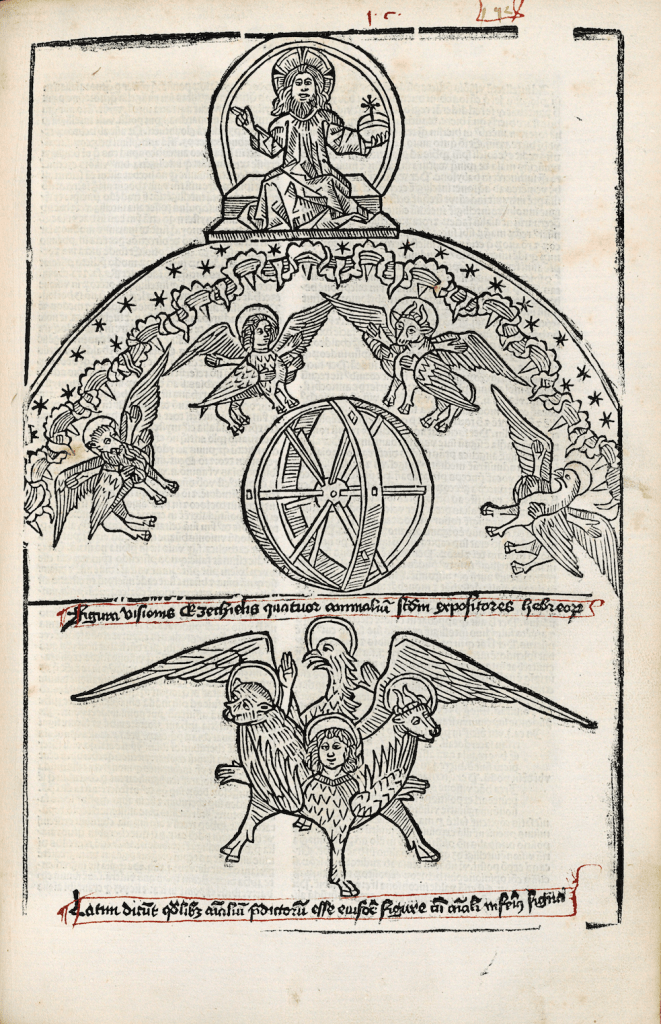

Left: Aaron the High Priest, Biblia, Koberger, 1493. Right: Ezekiel’s Vision, Biblia, Koberger, 1487.

❧ Simon Bevilaqua’s

Narrative Woodcuts

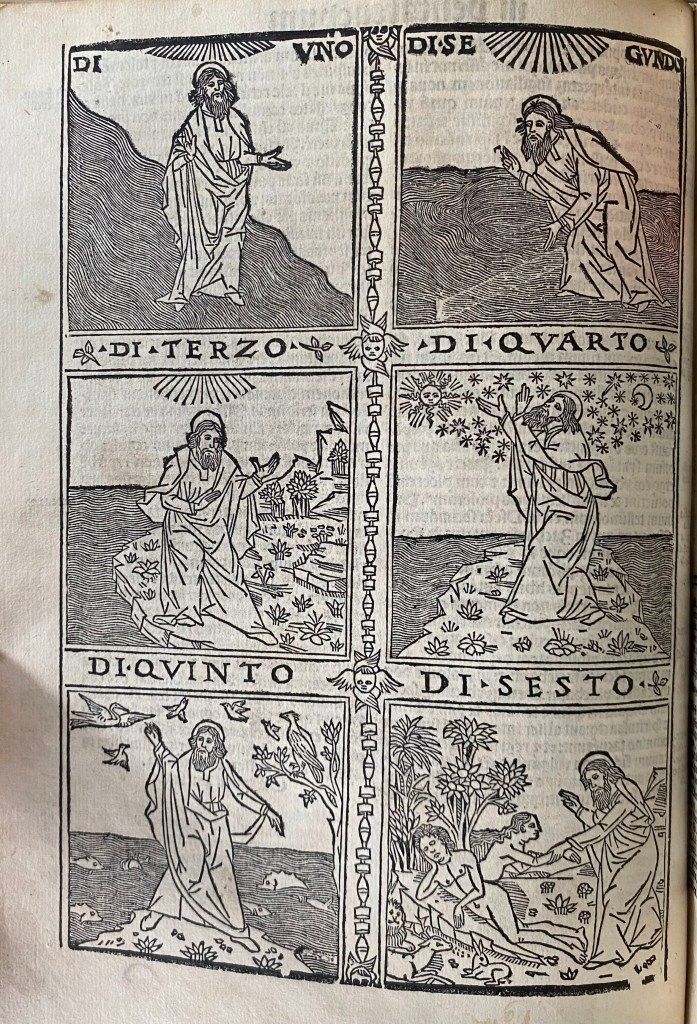

In the spring of 1498, Venetian printer Simon Bevilaqua published an extraordinary quarto Latin bible that included 71 integrated woodcut illustrations (no. 93). It also included a striking half-page woodcut depicting Solomon in three distinct attitudes (reclining, studying, and conversing) as well as a memorable full-page six-panel woodcut depicting God’s activities over the six days of creation (both below). Unlike the Koberger woodcuts, these woodcuts are not diagrammatic: instead they feature simple yet lively figures clearly intended to bring the biblical stories to life for readers of all walks of life.

Left: Six-panel Creation, Biblia, Bevilaqua, 1498. Right: Solomon, Biblia, Bevilaqua, 1498.

And yet, for all that, these charming woodcuts were not designed for Bevilaqua’s Latin Bible. The work of the Pico Master, they were instead commissioned by Bevilaqua’s fellow Venetian printer Lucantonio Giunta almost a decade earlier for his Italian bibles printed in 1490, 1492, and 1494. A close examination reveals, moreover, that Bevilaqua was more than merely inspired by Giunta’s woodcuts: he clearly used the very same woodblocks when he set to work on his own illustrated Latin bible in 1498 (below, left and right).

Left: Detail, Death of Jacob, Biblia, Giunta, 1490. Right: Death of Jacob, Biblia, Bevilaquia, 1498

It is not known how he arranged this with Giunta, but one can perhaps infer from the fact that he used only a fraction of the 386 woodcuts available to him (that being the number featured in Giunta’s earlier Italian bibles), that he rented individual woodblocks from Giunta at a rate that might have made a more profusely illustrated bible cost prohibitive. Add to that the fact that Bevilaqua was undoubtedly ahead of his time and the market for illustrated Latin bibles remained largely untested. It may be that bibles in Latin were considered too scholarly to benefit from illustrations (apart from the diagrammatic illustrations belonging to the Postilla). Or perhaps the additional cost illustrations entailed were thought to be unjustifiable. Whatever the reason, the woodcuts appearing in Bevilaqua’s 1498 Latin bible are confined largely to the beginning of the biblical books they illustrate — with the exception of Genesis. Remarkably, Bevilaqua included not a single woodcut in the entire book of Genesis, a book that in sixteenth-century Latin bibles would typically be among the most profusely illustrated. Despite its shortcomings and obvious economies, however, Bevilaqua’s edition marked a significant development in the evolution of illustrated Latin bibles. And, most importantly, it may have played a part in convincing Lucantonio Giunta to print his own illustrated Latin Bible a little more than a decade later.

❧ Lucantonio Giunta’s 1511

Illustrated Latin Bible

Lucantonio Giunta founded one of the most successful printing and publishing businesses of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Born in Florence in 1457, Giunta began publishing works in Venice in 1489, eventually entering the market as a printer as well in 1500. Relying on members of his large family, by the time of his death in 1538, he had established presses in Florence and Lyon, as well as successful bookshops in Spain, France, Portugal, Germany, and Belgium.

By the time Giunta began work on publishing his own illustrated Latin bible, the market for illustrated bibles in vernacular languages was comparatively well developed. Giunta’s own illustrated Italian bibles of the 1490s were undoubtedly successful. At the same time, Koberger and others had been printing illustrated German bibles since the 1480s. The only truly illustrated Latin bible from the incunable period, apart from the diagrammatic woodcuts created for Koberger’s 1485 edition of Lyra’s Postillae, was the lone Bible printed in Venice by Belivaqua in 1498. There is evidence to suggest that this Bible was printed in very large quantities. It certainly has an unusually high survival rate. The Universal Short Title Catalogue (USTC) records 157 copies held by institutional libraries around the world. That compares favourably with, for example, 100 surviving copies of the quarto Latin bible published in Venice by Georgius Arrivabenus in 1487 (no. 69). That high survival rate, together with the fact that another illustrated Latin bible did not appear for more than a decade, together suggest that Belivaqua’s sales may not have been particularly brisk.

By 1511, Giunta was willing to gamble that the market had changed. That year Giunta published a quarto illustrated Latin bible featuring the same woodcuts that both his 1490s Italian bibles and Belivaqua’s 1498 Latin bible contained (no. 113). But where Belivaqua had included only 73 woodcut illustrations, Giunta included 145 woodcuts — including both the half-page Solomon woodcut and the six-panel creation woodcut (in fact, the creation woodcut appears twice: facing both Jerome’s introductory commentary and the opening page of the book of Genesis). The larger number of woodcuts Giunta included resulted in a much more attractive bible — partly printed in red and black (below left). Giunta also included, and thereby revived, the Eusebian Gospel Canon Tables — an adjunct that had not appeared in a Latin bible since the 1480s (below right). For his text, Giunta relied on the Vulgate edited by Abertus Castellanus, first published by Thielman Kerver in 1504 (no. 100).

Left: Genesis Incipit, Biblia, Giunta, 1511. Right: Eusebian Canon Tables, Biblia, Giunta, 1511.

Perhaps in part because Giunta had already established (or was in the process of establishing) a presence across much of Europe, this 1511 Latin bible achieved an unprecedented, even breathtaking, degree of influence. Giunta’s woodcuts were widely copied by other printers, particularly those in Lyon, and in the process they became standard representations of the biblical text. Indeed, it was not until the first woodcuts designed by Hans Holbein, themselves partly influenced by Giunta’s illustrations, appeared in a 1538 Latin bible published in Lyon by Melchior and Gaspar Treschsel, that the appearance of illustrated Latin bibles began to evolve in any significant way. Though outside the scope of this bibliography, it would be difficult to overstate the role Holbein played from the late 1530s onward — not only in providing illustrations for bibles in all languages, but also in uniting German (Protestant) and Italian (Catholic) traditions that to this point had remained mostly distinct.

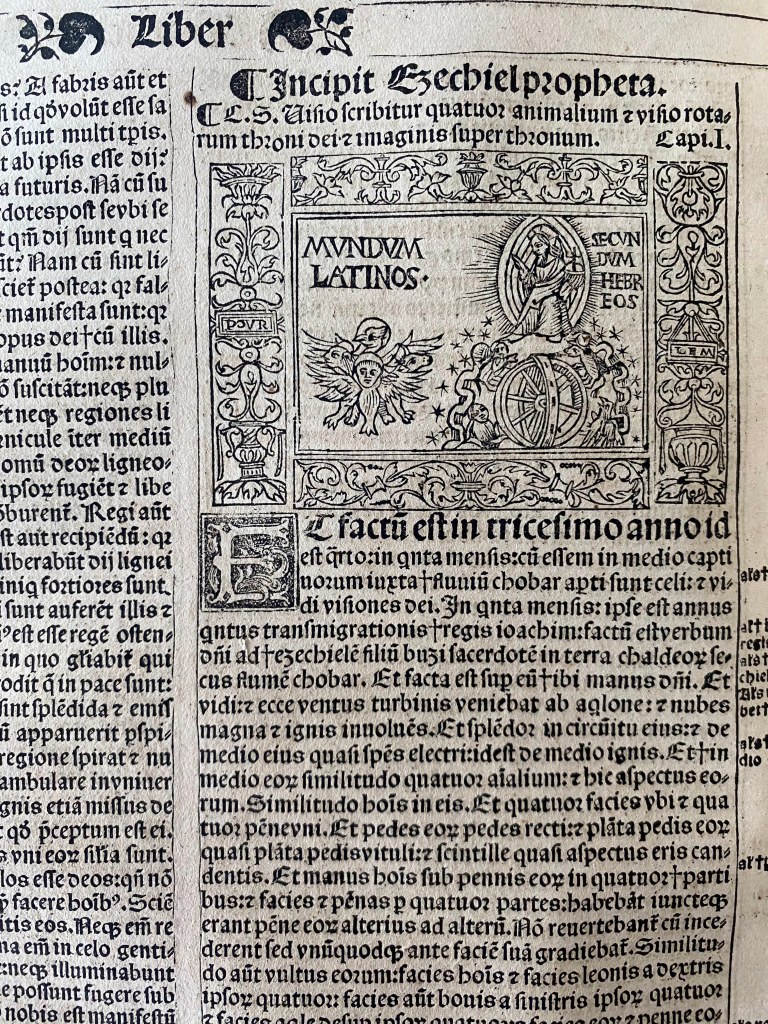

Any discussion of Giunta’s 1511 illustrated Latin Bible would be incomplete without also noting the fact that, by the time Giunta used these woodblocks to produce this groundbreaking edition of the bible, they were already more than twenty years old. And, at least in some cases, they were beginning to show significant signs of wear. One of the most striking consequences of that wear can be seen in the diagram of Ezekiel’s vision — an image that also figured prominently in the Postillae woodcuts featured in the multi-volume Koberger bibles of the 1480s and 1490s (see above). Here we have the visual juxtaposition of two images, one designed to read secundum Latinos and the other secundum Hebreos. Taken together these images are intended to foreground a discrepancy between the description of Ezekiel’s Vision in the Greek Septuagint and the Hebrew texts noted both by St. Jerome and Nicholas de Lyra. But half of the word secundum (preceding Latinos) is garbled in Giunta’s 1511 Latin Bible (below, upper left left). Remarkably, this marred text resulted in entirely new woodcuts being created that were, from their very first use, largely unintelligible. In subsequent illustrated Latin bibles, for example those published by Etienne Gueynard and Jean Crespin in 1522 and 1527 (nos. 137 and 159), one can see that the word secundum has become mundum — thus obscuring the original meaning of both Koberger’s and Giunta’s original woodcuts made during the incunable period (below, lower left and right).

Top-Left: Ezekiel’s Vision, Biblia, Giunta, 1511. Top-Right: Death of Jacob, Biblia, Giunta, 1511.

Bottom-Left: Ezekiel’s Vision, Biblia, Gueynard, 1522. Bottom-Right: Ezekiel’s Vision, Biblia, Crespin, 1527.

❧ Illustrated Latin Bibles

Printed in Lyon

As the sixteenth century progressed, Jacques Sacon became almost as famous for producing Latin bibles as Anton Koberger. In fact, the two often worked together — Sacon providing the labour and Koberger the money. Active in Lyon since 1498, Sacon published his first Latin Bible in 1506 (no. 102). It was a handsome bible and one that Sacon was determined would be successful. Although it contained no illustrations, the title page bore a bright red printer’s device so much like the device used by Lucantonio Giunta that it may well have been a deliberate effort to fool potential buyers into thinking they were purchasing one of Giunta’s own bibles (below left). However that may be, after printing two similar editions, another folio in 1509, and an octavo in 1511 (nos. 107, 112), neither with any woodcuts (apart from those on the title pages), Sacon suddenly adopted an entirely new strategy.

Left: Title page, Biblia, Sacon, 1506. Right: Title page, Biblia, Sacon, 1512.

Almost from the very first moment Sacon laid eyes on a copy of Lucantonio Giunta’s beautifully illustrated Latin Bible published in 1511, he seems to have determined to publish one of his own. But, unlike Simon Bevilaqua, he had no intention of renting Giunta’s woodblocks. Instead, after securing financial backing from Anton Koberger, Sacon arranged to have 145 new woodcuts designed that, though more elaborate, were clearly modelled on those that appeared in Giunta’s 1511 Latin Bible. A mere fourteen months after the appearance of Giunta’s illustrated quarto Latin Bible, Sacon’s impressive new illustrated Latin Bible went on sale (above right) — not in quarto format but as a Royal Folio (no. 115). The financial gamble paid off handsomely. A second edition featuring the same woodcuts was rushed into print by Sacon (again, at the expense of Koberger) that same year. Additonal illustrated folios using the same woodblocks followed in 1513, 1515, 1516, and 1518 (nos. 118, 122, 124, and 127). In 1519, Sacon printed a new edition featuring more detailed woodcuts, though still based on these earlier designs (no. 128). Although the collaboration between Sacon and Koberger (his heirs by this time — Koberger died in 1513) was remarkably durable, there is a hint of some tension between the two houses in the early 1520s. At that time, Koberger’s heirs also partnered with Jean Marion in 1520 and Friedrich Peypus in 1522 and 1523 for the production of several further editions (nos. 132, 139, 142).

Top-Left: Creation, Biblia, Giunta, 1511. Top-Right: Creation, Biblia, Sacon/Koberger, 1516

Bottom-Left: Creation, Biblia, Crespin, 1527. Bottom-Right: Creation, Biblia, Mareschal, 1519.

Despite their remarkable success in the market, rival printers and publishers were not content to leave the field entirely to Sacon and Koberger. Some, like Jean Crespin, appear to have made arrangements with Sacon to rent or use his woodblocks for the production of his own illustrated Latin bibles. Others, such as Etienne Gueynard and Jacques Mareschal, commissioned entirely new woodcuts — but woodcuts that were nevertheless closely modelled on the Giunta originals. This line of influence, running from Giunta through Sacon to other Lyonese printers, can be seen perhaps nowhere more clearly than in the six-panel creation woodcuts above. These large woodcuts were featured prominently at the beginning of all these bibles facing the opening page of Genesis (oddly, Gueynard included this woodcut in his 1512 and 1516 Latin bibles but not the editions he printed in 1520, 1522, and 1526 — perhaps the woodblock was lost, damaged, or destroyed sometimes between 1516 and 1520).

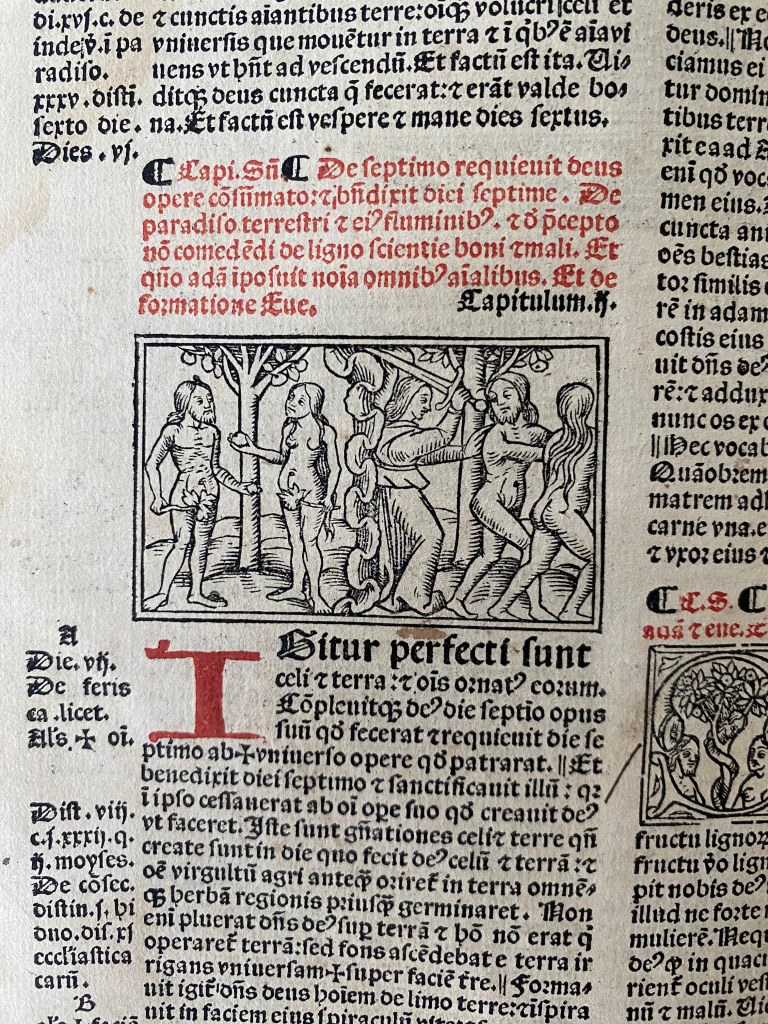

Giunta’s original Creation woodcut, first used in his 1490 Italian Bible, but here pictured as it appeared in the 1511 Latin Bible, was the model for Sacon’s woodcut (above, upper right). That seems to be the very same woodcut used by Crespin in 1527 (above, lower left). Mareschel, by contrast, commissioned a new woodcut for his octavo bibles but clearly stipulated that they should reflect the same layout and appearance as the earlier Giunta and Sacon exemplars (above, lower right). One can see similar lines of sharp influence running through woodcuts appearing within these bibles as well. In the gallery below, for example, we find three depictions of the Fall juxtaposed in a single woodcut with the Expulsion from Eden. Although there are minor differences, it can hardly be doubted that the Giunta woodcut, perhaps by way of Sacon, served as the model for the new woodcuts used by Etienne Gueynard in his 1516, 1520, 1522, and 1526 Latin bibles (Gueynard’s 1512 Latin bible contains far fewer illustrations), and Jean Crespin’s 1527 and 1529 Latin bibles. Incidentally, these five Gueynard bibles are the only Latin bibles published in this period that were printed in red and black throughout (that is, on every page). Although that effectively doubled the presswork required to produce them, they are for that reason among the most beautiful bibles produced in the sixteenth century.

Left: The Fall, Biblia, Giunta, 1511. Middle: The Fall, Biblia, Gueynard, 1522. Right: The Fall, Biblia, Crespin, 1527.

Concluding Thoughts

It seems clear from this evidence that, beginning in the sixteenth century, something significant was happening in the ways Europeans engaged with the Bible — and the Latin bible in particular. While illustrated bibles in the vernacular had been available since the 1480s and 1490s, the subsequent vibrancy of the market for illustrated Latin bibles suggests there were significant numbers of lay readers who seemed to prefer to read the Bible in Latin. It will be remembered that before 1500, Koberger seemed decidedly reluctant to produce an illustrated Latin bible and did so only when he could marry the biblical text to illustrations prepared for Nicholas of Lyra’s Postillae — a multi-volume scholarly edition that could be acquired only at considerable expense. Later, when Simon Bevilaqua published his own quarto illustrated Latin Bible using some of the woodcuts Lucantonio Giunta had originally commissioned for his 1490 Italian Bible, he seems to have met with only moderate success in the market. But everything suddenly changed the moment Giunta published his own illustrated quarto Latin Bible in 1511. That Bible was a spark that lit a fire — particularly in Lyon. Suddenly the market for illustrated Latin bibles could hardly be satisfied even by three or four printers as they issued a cataract of new folios, quartos, and octavos — all illustrated with woodcuts modelled directly on Giunta’s originals.

Reading itself leaves few artefacts. One can thus only speculate about why so many readers seemed to prefer these illustrated Lain bibles over bibles printed in the vernacular. Though the Roman Catholic Church would make no official pronouncements about the Biblia Vulgata until 1546 at the Council of Trent, perhaps the antiquity, the familiarity, and even the elegance of the Latin bible combined to make it particularly attractive to readers — readers who, it must be remembered, were already accustomed to hearing the Latin Mass and using their Latin prayerbooks on a daily basis. This would suggest that, though it is certainly true that not everyone could read, recent historians may have significantly overstated the degree to which Latin was an inaccessible language to lay readers.

❧ Further Reading

- James Strachan, Early Bible Illustrations: A Short Study, Cambridge University Press, 1957.

- David H. Price, In the Beginning was the Image: Art and the Reformation Bible, Oxford University Press, 2021.