Why did some early printed bibles survive in relatively large numbers, while others are known to us in just a handful of copies? The answer lies in a complex web of factors, including the circumstances of their production, the quality of materials used, the social and religious context of their distribution, and the historical events that followed. Bibles printed in large quantities, particularly those from well-established presses, were more likely to be widely distributed and thus had a better chance of survival. The geographic location of the printing press also played a significant role—bibles produced in major centres of trade and intellectual activity had broader dissemination networks. Additionally, the period during which a Bible was printed could influence its fate; texts produced during times of political stability or religious fervour were often more highly valued and carefully preserved. Conversely, bibles printed in regions affected by wars, religious upheavals, or economic downturns might have faced destruction or neglect. Ultimately, the survival rates of these early printed works reflect not just the technical capabilities of their producers but also the broader cultural, social, and historical forces at play during their creation and beyond.

❧ Case Study: The 1460s

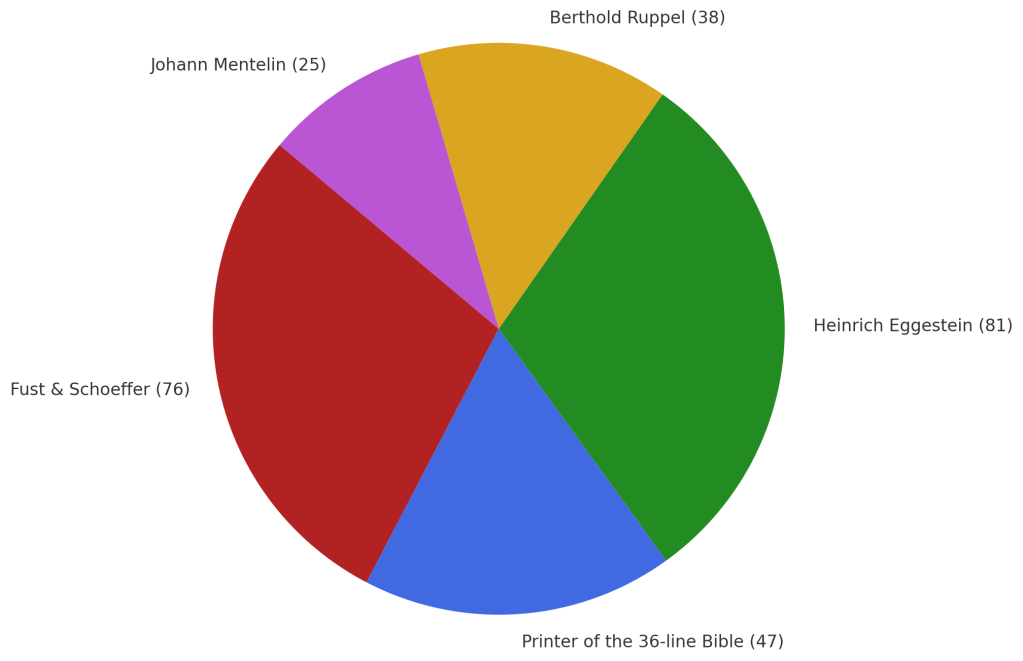

Throughout the 1460s, the craft of printing remained in its infancy, confined largely to a handful of cities within the Holy Roman Empire. The process of casting movable type was labour-intensive and costly, and the number of editions produced—especially of large-format works like the Bible—remained modest. Over the course of the decade, only six distinct editions of the Latin Bible were printed, a figure that reflects both the technical limitations of early presses and the deliberate, conservative spread of the new technology.

The principal printing centres of the period—Mainz, Strasbourg, Bamberg, and Basel—were all situated along key trade routes or within intellectual heartlands. These cities offered early printers ready access to literate markets already shaped by centuries of manuscript culture. Much of Europe, however, remained untouched by the press, and manuscript books continued to dominate both ecclesiastical and private collections.

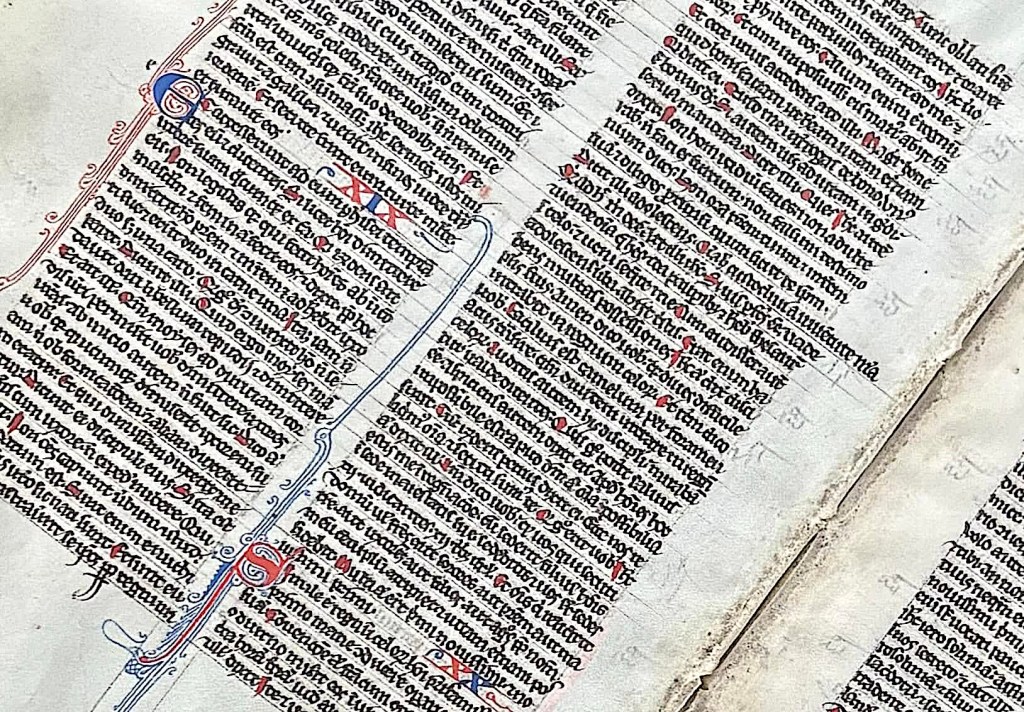

Among the earliest printers—many of whom had direct ties to Gutenberg—were Johann Mentelin in Strasbourg, and Johann Fust and Peter Schoeffer in Mainz. Printing was a craft that could only be acquired from those already skilled in it, and the transmission of this knowledge remained closely guarded in the early years. The bibles produced by these men and their contemporaries were deliberately modelled on prestigious manuscript codices: imposing folios, rubricated by hand, and often sold unbound to allow for bespoke binding and illumination. Despite their mechanical origins, these books were expensive to produce and far from cheap to purchase. The capital required to fund a Bible project was substantial, and print runs were limited—typically ranging from a few dozen to several hundred copies.

Given this modest scale of production, coupled with the hazards of time, war, and reform, it is not surprising that only a fraction of these early bibles survive. Of the six separate editions printed in the 1460s, just 267 copies (both fragmentary and complete) are known today.

❧ The Dawn of Print: Balancing Risk and Reward

Johann Fust and Peter Schoeffer, Gutenberg’s former collaborators who took over his workshop after launching legal action against the inventor, occupied a place at the very forefront of the printing revolution. Yet their 1460 edition of the Latin Bible, a monumental undertaking comparable to Gutenberg’s own in its technical complexity, likely had a very limited print run. This is hardly surprising. These men had a front row seat to Gutenberg’s own financial struggles and eventual bankruptcy despite his extraordinary invention. And unlike scribal work, early printshops had to produce not one but dozens or even hundreds of copies of a book before receiving any return on their initial investment in labour and materials. Johann Fust was a keen businessman with the sense needed to avoid’s Gutenberg’s financial mistakes. Carefully measuring risk against reward, it is probable that Fust and Schoeffer printed no more than a hundred copies — fewer copies than Gutenberg himself printed — of this 1460 edition of the Latin Bible.

By the time Fust and Schoffer set about printing a second Bible together in 1462, they no doubt had learned a great deal — both about the logistics of production and the best methods for marketing their wares. This allowed them to make a larger capital investment in paper, typesetting, and presswork without worrying about realising an immediate return on their investment. The result was an edition of perhaps as many as three hundred copies — together with the associated profits that this much larger edition promised. These new printed bibles, though undoubtedly expensive, were nevertheless not as costly as their manuscript counterparts, helping Fust and Schoeffer stimulate new demand from religious institutions and wealthy patrons not only in Germany, but across Europe. The wider geographical distribution of this edition increased the likelihood that a significant number of these bibles would survive. In fact, there remain to us today more copies — more than 75 — of the Fust and Schoeffer 1462 Bible than of any other Bible printed before 1475.

❧ Geography and the Spread of the Printed Word

The geographical location of printing centres significantly influenced the distribution and survival of early Bibles. Mainz, situated along the Rhine River, benefitted from its position at a crossroads of trade and intellectual exchange. The 1462 Fust and Schoeffer Bible, for instance, was likely transported along these trade routes, reaching cities and religious institutions across Europe. This widespread distribution contributed to its unusually high survival rate.

In contrast, Johann Pfister’s 1466 Bible, printed in Bamberg, faced geographical challenges. Bamberg’s distance from major trade networks limited the reach of this edition, confining it to a more regional audience. This restricted circulation reduced the chances of long-term preservation, leading to fewer surviving copies.

Meanwhile, Sweynheym and Pannartz’s 1469 Bible, printed in Rome, benefitted from the city’s status as a cultural and religious centre. As the seat of the Papacy, Rome offered a fertile market for religious texts. However, many early Italian editions were produced for scholarly audiences, concentrating their distribution in monastic and university libraries. Although these settings often ensured careful preservation, they were also vulnerable to later conflicts and shifts in religious doctrine.

❧ Wars, Disasters, and Religious Upheavals

The survival of early printed books was shaped both by conflict and craftsmanship. The 1462 Bible of Johann Fust and Peter Schoeffer—commonly known as the Biblia pulchra for its extraordinary beauty—was printed on the eve of the Mainz Diocesan Feud (1461–1463), a civil war that might easily have led to its complete destruction. Remarkably, however, this edition boasts the highest known survival rate of any Latin Bible printed in the 1460s. Its remarkable preservation owes much to both the strength of the printers’ early distribution networks (that removed many copies from the site of the conflict) and the reverence with which this superbly executed volume was received across Europe.

Yet throughout Europe, wars, religious reforms, and natural disasters posed constant threats to early printed books. The Protestant Reformation, for instance, saw the destruction of many Catholic texts. The dissolution of the monasteries in England during the 1530s led to the dispersal and destruction of numerous monastic libraries, resulting in the loss of countless religious manuscripts and early printed books. Similarly, the Wars of Religion in France (1562–1598) devastated religious institutions, often targeting Catholic libraries for destruction. The very earliest printed bibles, however, particularly those printed before the 1490s, remained in a class of their own: because such bibles were typically produced without extra-biblical notes, references, or commentaries (apart from the ubiquitous prefaces written by Jerome), they would have remained largely acceptable to Christian readers who perceived themselves to be outside the embrace of the Roman Catholic Church.

Of course, none of this prevented the loss of copies through natural disasters: fires, floods, and other calamities frequently ravaged libraries and monasteries. Bibles subjected to frequent handling were also prone to deterioration, while those kept sequestered and in controlled environments had a better chance of survival.

❧ Status, Expense, and Rarity of Early Printed Bibles

The 1460s witnessed not only technological improvements but also shifting attitudes toward print. Printers continually experimented with ink formulations, type design, and press mechanics, all of which contributed to more durable and aesthetically pleasing books. These refinements helped bridge the gap between manuscript and print, making the new medium more acceptable to conservative audiences.

Despite these advances, the transition from manuscript to print was not immediate. Some monastic communities embraced printed bibles as efficient and reliable tools, while others resisted, viewing them as inferior to hand-copied texts. This hesitation limited the initial reach of printed works, even as their intrinsic value began to be recognised.

Nevertheless, owning a Bible of any kind in the fifteenth century was a mark of prestige. The high cost of production, coupled with the quality of materials, made these books luxury items. Because wealthy patrons and religious institutions were the primary owners, many of these bibles were relatively well insulated from the vagaries of accidental destruction.

❧ Case Study: The 1490s

This period marks a significant departure from the 1460s, reflecting advancements in printing technology, distribution, and the socio-political climate of the time. Understanding why certain editions from the 1490s have survived in greater numbers involves exploring the impact of format, place of printing, the presence of commentaries and illustrations, as well as the historical context that influenced the production and preservation of these works.

❧ The Evolution of Print Culture in the 1490s

By the 1490s, the printing industry had matured considerably compared to its nascent stages in the 1460s. This decade saw an increase in the number of editions being produced, as well as a diversification in the types of bibles printed. One of the most striking differences between the 1460s and the 1490s is the survival rate of these texts. While bibles from the 1460s often survive in only a handful of copies, many editions from the 1490s are known in tens or even hundreds of copies.

Several factors contribute to this discrepancy. First, the technology of printing had improved significantly by the 1490s. Printers had mastered the art of producing books more efficiently and in larger quantities, which naturally led to higher survival rates. The introduction of the octavo format, first seen in Johann Froben’s 1491 edition, made bibles more affordable and accessible to a broader audience. This smaller, more portable format was likely produced in larger numbers and distributed more widely, leading to a higher number of surviving copies.

❧ Geographic Distribution and Major Printing Centres

The place of printing played a crucial role in the survival rates of these bibles. By the 1490s, several cities had established themselves as major centres of printing. Venice, Basel, Nuremberg, and Strasbourg were among the most important, with printers like Hieronymus de Paganinis, Johann Froben, and Anton Koberger leading the way. These cities were not only hubs of intellectual activity but also strategically located along major trade routes, facilitating the wide distribution of their printed works.

For instance, Anton Koberger’s 1493 Bible, printed in Nuremberg, survives in some 214 known copies. Koberger was one of the most successful printers of his time, with a vast network of distribution that spanned Europe. His bibles, often lavishly illustrated and accompanied by extensive commentaries, were highly valued and thus more likely to be preserved.

In contrast, bibles printed in smaller or less central locations, such as the 1490 edition by Jacobus Maillet in Lyon, survives in far fewer copies, with only 19 known examples. While Lyon was becoming a significant centre for printing, it did not yet exercise the same reach or influence as Venice or Nuremberg. This discrepancy highlights the importance of location in determining the survival rates of early printed works.

❧ The Impact of Format and Content

The format of the Bibles also had a significant impact on their survival. Octavo and quarto formats, like those used by Froben and Paganinis, were more economical to produce and easier to transport. This accessibility likely led to larger print runs and broader distribution, potentially contributing to number of surviving copies. Froben’s 1495 octavo Bible, for example, is known to us in 225 institutional copies, indicating its widespread popularity and preservation. At the same time, the transition from large folio editions to smaller octavos or quartos also coincided with broader shifts in how bibles were read and used. For many owners, these portable bibles were not treasures to be kept in pristine condition, but practical tools for the development of one’s spiritual life, read and re-read until they fell apart. The increasing availability of printed texts may also have diminished the perceived need for preservation, as new copies could be acquired more readily.

The content of these bibles also played a crucial role in their survival. Many folio editions from the 1490s included extensive commentaries, glosses, and other scholarly apparatus. The four-volume folio Bible printed by Paganinus de Paganinis in 1495, for example, included both the commentaries of Nicholas de Lyra and the Glossa Ordinaria. The inclusion of these authoritative commentaries clearly made this edition a particularly valuable resource for scholars and clergy working in institutional settings–evidenced by the fact that more than 200 copies of this particular edition survive today.

Illustrations, too, were an important factor. Bibles that included woodcut illustrations, like Simon Bevilaqua’s 1498 edition, which featured 73 narrative woodcuts, were likely considered more precious and were therefore more carefully preserved. Bevilaqua’s Bible survives in 157 copies, reflecting the added value that these illustrations provided.

❧ Historical Context and Preservation

The broader historical context of the 1490s also contributed to the higher survival rates of these bibles. By this time, Europe was experiencing a period of relative political stability, particularly compared to the earlier decades of the century. The Wars of the Roses in England had ended, the Hundred Years’ War was long over, and the major powers of Europe were entering a period of consolidation and exploration. This stability allowed for the growth of the book trade and the establishment of libraries and private collections, where these bibles could be preserved.

Additionally, the 1490s were a time of increasing religious and intellectual activity, spurred in part by the humanist movement. The demand for religious texts, especially those that included scholarly commentaries, was high. Printers responded to this demand by producing bibles that were not only religious texts but also scholarly tools, filled with glosses, commentaries, and concordances. These features made the bibles more valuable to their owners and more likely to be preserved over the centuries.

❧ Comparing the 1460s and the 1490s

When comparing the survival rates of bibles from the 1460s and the 1490s, the differences are stark. The higher survival rates of the 1490s can be attributed to several factors: improvements in printing technology, the establishment of major printing centres, the use of more portable and accessible formats, and the inclusion of valuable content like commentaries and illustrations. Furthermore, the relative political and social stability of the 1490s, combined with the increasing demand for religious and scholarly texts, created an environment conducive to the preservation of these works.

In contrast, the 1460s were a time of experimentation and instability. The printing press was still a new technology, and printers were finding their way in an uncertain market. There were far fewer editions printed and those that were printed originated in a much more confined geographical area. In addition, the aftermath of the Hundred Years’ War and ongoing conflicts like the Wars of the Roses, made the preservation of books more challenging overall. As a result, survivals from the 1460s today are far less common.

❧ Case Study: The 1510s

The survival rate of bibles printed in the early sixteenth century is dramatically lower than that of bibles printed during the incunable period. Several factors contributed to this, including the religious upheavals of the Protestant Reformation, a gradual decline in production quality, a higher proportion of smaller format editions, and an overall shift in the way people understood the Bible’s role in society. Additionally, the ways in which these Bibles were collected and preserved—or neglected—by both private individuals and institutions in subsequent centuries have had lasting impacts on the survival and condition of individual copies to the present day.

❧ The Impact of the Reformation and Religious Turmoil

The onset of the Protestant Reformation in 1517 significantly affected the preservation of Latin bibles, particularly those associated with Roman Catholicism. As Protestantism spread across Europe, Latin bibles were often viewed with suspicion or hostility, leading to their neglect or destruction, especially in regions like France and the Holy Roman Empire, where religious conflict and iconoclasm became particularly intense. For example, the Sacon/Koberger bibles, despite their high production quality and rich illustrations, survive in relatively few copies. That low survival rate can in large part be traced back to their place of manufacture: Lyon.

Lyon’s religious environment during this and the following decades was marked by significant turmoil. The city, a major centre of printing and commerce, became a focal point of religious conflict in the wake of the Reformation. Initially, Lyon remained a stronghold of Catholicism, but by the 1520s, Protestant ideas began to take root, particularly among the city’s merchants and printers. The spread of Lutheran and later Calvinist doctrines led to rising tensions between Catholics and Protestants, culminating in several violent outbreaks. In 1562, the city witnessed the Massacre of Vassy, where Protestant worshippers were attacked by Catholics, an event that sparked the French Wars of Religion. Lyon was frequently contested during these wars, changing hands between Catholic and Protestant forces, which led to widespread destruction, including the loss of many books and other cultural treasures. Local copies of bibles printed by Sacon for Anton Koberger may have been associated by some with Roman Catholicism and were thus somewhat more likely to be lost during periods of religious violence.

In contrast, illustrated Latin bibles printed in Italy, such as those by Lucantonio Giunta in Venice, fared better in large part because Catholicism continued to dominate on the Italian peninsula. Venice was a particularly strong hub of Catholic intellectual and artistic life and maintained strong ties to the Vatican. As a result, Venice’s relative political and religious stability, combined with its flourishing arts and printing industries, contributed to the higher survival rates of bibles produced there. Giunta’s 1519 octavo Bible, adorned with nearly 200 woodcuts, is a prime example of a work that can still be found in good condition and with some degree of frequency. The emphasis Giunta placed on especially lavish illustrations and Catholic iconography meant that this particular Bible was highly valued by collectors as well as institutions, despite its small size and relatively late appearance.

❧ The Evolving Role of Bibles in Society

The role of the Bible in society was also evolving during the 1510s. The rise of humanism and the increasing demand for scholarly texts led to the production of more and more bibles that contained tools to aid study, facilitate memorisation, and even provoke theological debate. At the same time, the printing industry itself had become progressively more commercialised as pressure mounted to produce larger quantities of books at a lower cost. This shift often resulted in the use of lower-quality paper, inks, and bindings, which made these bibles more susceptible to damage over time. The wear and tear associated with the more intensive use these bibles received, combined with an overall decline in material quality, yielded conditions were fewer examples were likely to survive in the longer term.

Additionally, the increased demand for affordable books led to the production of more and more editions of smaller and more portable formats. While bibles printed in octavo and smaller formats were cheaper and more affordable, that meant that they were often used in everyday life and in conditions that could readily lead to material deterioration. The contrast between the heavily worn copies from the 1510s and the relatively well-preserved folios and quartos from the incunable period highlights the impact of this shift in both methods of production and daily use. The very small pocket Bible printed by Wolfgang Hopyl in 1510, for example, can today be found in only five institutional libraries worldwide.

❧ Collecting Early Sixteenth-Century Bibles

The survival rate of bibles printed in the early sixteenth century was further diminished by the neglect of these editions in subsequent centuries. Unlike incunabula, which were highly prized for their grandeur and historical significance, bibles from this later period were often overlooked by both private and institutional collectors. And as the systematic practice of rare book collecting began to take firmer shape in the eighteenth century among private collectors, the focus was predominantly on incunabula. In the same way, libraries and other large public institutions often prioritised manuscripts and incunabula as the most ancient and significant texts, reinforcing the idea that works from the early sixteenth century were of little importance. This focus was further entrenched by the creation of bibliographies and catalogues that also privileged incunabula. This emphasis, combined with the material vulnerabilities of sixteenth-century books, led to decidedly poorer survival outcomes as they were far less likely to be rebound in fine bindings or especially prised by their owners.

❧ Rediscovery and Modern Collecting

It was not until the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries that bibles printed during the sixteenth century began to receive renewed attention . The rise of bibliographic studies and the growing interest in the history of the book led to a reevaluation of these texts, which were increasingly recognised for their historical significance and the insights they offered into these early years of print culture. Sadly, by this time, many bibles from the period had already suffered significant damage or had been lost entirely. The condition of those that did survive often reflected the neglect and rough handling they had endured, with missing leaves, waterstains, and damaged bindings.

Modern collectors and institutions have since worked to preserve and restore these bibles, recognising their value as historical and artistic artefacts. Efforts to stabilise and conserve surviving copies have helped to prevent further deterioration, and advances in technology have allowed for the digitisation of many of these works, ensuring their accessibility to those who appreciate the insights they provide on a pivotal period in the history of printing and religious change.

❧ The Legacy of Survival

Neglected by early collectors, vulnerable to physical deterioration, and at risk from religious and political upheavals, every individual copy that remains to us today serves as a reminder of the complex history it has endured—a history shaped by the shifting tides of religious belief, the evolving practices of book collecting, and the remorseless passage of time. Indeed, it is precisely this fragility that makes the legacy of these bibles so powerful. They are remarkable witnesses to the violence of history itself as well as to our own changing values as human beings–values that ultimately determine what is preserved and what is lost to future generations.