The complicated story of the Latin Bible in the West before the appearance of Gutenberg’s printing press in the mid-fifteenth century would take many volumes to recount. This page provides just a brief sketch of this long history by focusing on the foundational work of St Jerome, the remarkable Codex Amiatinus (and the early pandects it represents), Carolingian efforts to correct the Vulgate, the and the rise of the Paris Bible in response to the intellectual and pastoral needs of the High Middle Ages. Together, these developments shaped both the form and content of the Latin Bible — all while laying the groundwork for the changes that Gutenberg’s revolutionary printed Bible would eventually inaugurate.

❧ St. Jerome and the Vetus Latina Bible

In the late fourth century, St Jerome undertook a monumental task at the behest of Pope Damasus I: revising the old Latin translations of the Bible, collectively known as the Vetus Latina, to produce a more coherent and accurate text. The result was a mostly new translation that would dominate Western Christendom for over a millennium. Jerome approached the task with philological precision, revising the Gospels based on the best Greek manuscripts available and translating the Hebrew Scriptures afresh, thereby bypassing the Greek Septuagint used by earlier translators.

Jerome’s meticulous scholarship was not without controversy. His prologues explicitly demoted certain books, like Tobit and Judith, to an apocryphal status because they did not appear in the Hebrew canon. Despite this, these texts, along with others such as Wisdom and Ecclesiasticus, found their way into the Vulgate. Jerome also employed exegetical materials from Greek scholars and relied on Origen’s Hexapla — a massive critical edition of the Hebrew Bible offering six parallel versions in Hebrew and Greek — to inform his work. While the Vulgate’s composite nature — incorporating Vetus Latina remnants as well as translations by Jerome’s contemporaries — blurred its singular authorship, it nevertheless managed to achieve what Pope Damasus envisioned: a definitive Latin Bible.

The influence of Jerome’s translation was profound. By the thirteenth century, it had become known as the versio vulgata — or the “commonly used translation” — of the Church. But it would be a mistake to think that its importance was solely or even chiefly theological in nature. Jerome’s work signified a critical watershed in the intellectual history of the West, marrying rigorous scholarship and ecclesiastical purpose with a deep sense of Christian identity. As a common translation, the Vulgate was critical in reinforcing the notion that Christians across Europe belonged to a single Church founded upon a coherent doctrine. While the Vulgate undoubtedly provided an indispensable foundation upon which scholars could construct their theological inquiries, for the laity its words combined to become the single and ubiquitous voice of Scripture through which Christ spoke to them directly in the liturgy.

An important early witness to the adoption of Jerome’s Vulgate is the Codex Floriacensis (also known as the Fleury Palimpsest), housed today in the Bibliothèque Nationale. The manuscript takes its name from the Abbey of Fleury, also known as Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire, in central France, where it was preserved for centuries. The clarity and regularity of the script indicate that the codex was likely produced in a scriptorium of some prestige, suggesting origins in an ecclesiastical or monastic setting. Dating to around 450–550, the manuscript contains portions of the New Testament, including Acts, the Catholic Epistles, and Revelation. As one of the earliest extant examples of Jerome’s work, it also reveals the transitional nature of biblical texts in this period. While largely reflecting Jerome’s revisions, the codex retains traces of the Vetus Latina, illustrating how the Vulgate only gradually supplanted earlier translations.

❧ Early Pandects and the Codex Amiatinus

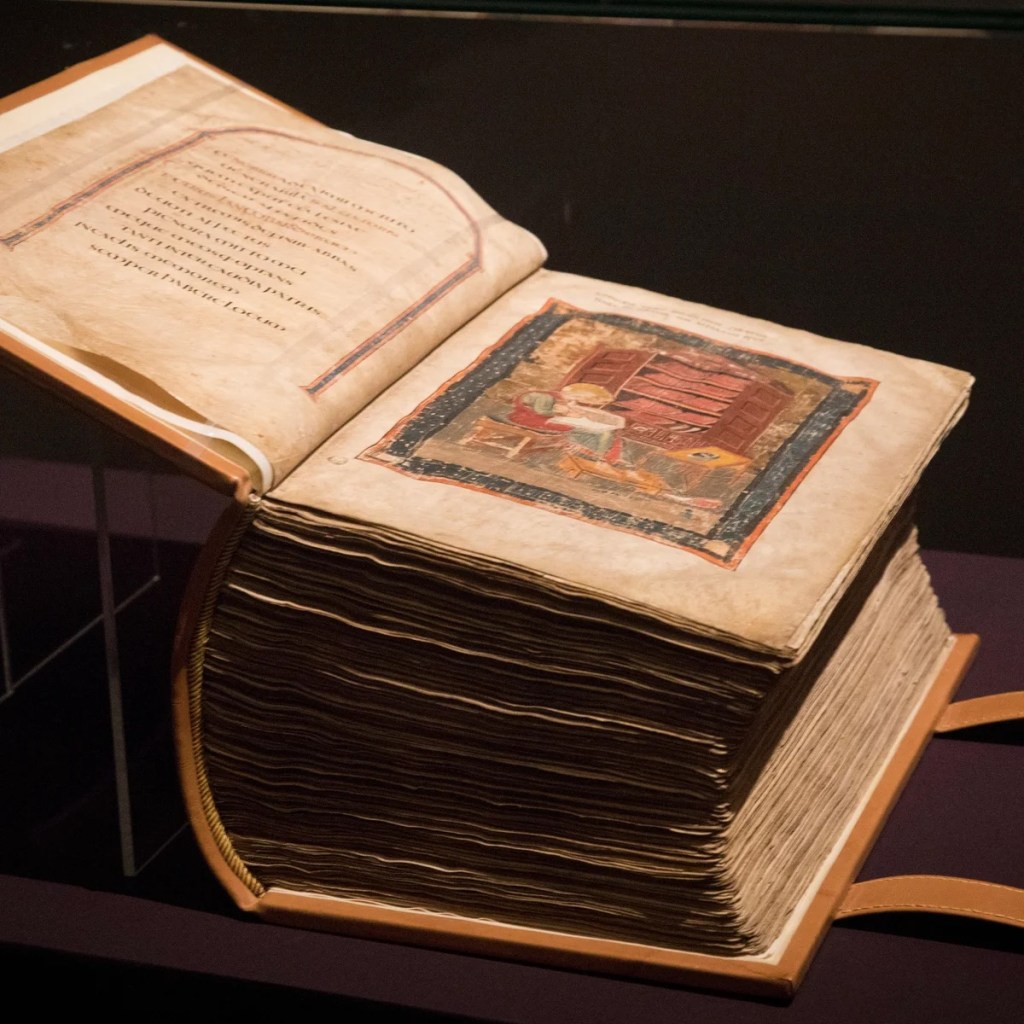

This transitional phase in biblical texts, epitomised by the Fleury Palimpsest, laid the groundwork for later efforts to consolidate and standardise the Scriptures. Among these, the Codex Amiatinus stands as a towering achievement in the history of biblical manuscripts. Created at the twin monasteries of Wearmouth and Jarrow in the early eighth century under the direction of Abbot Ceolfrid, this massive pandect — a single book containing the entire Bible — was intended as a gift for Pope Gregory II. Although Ceolfrid passed away en route to Rome in 716, the codex eventually reached its destination, solidifying its role as a bridge between Anglo-Saxon England and the heart of Christendom. Today, it resides in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence, where it continues to serve as a powerful reminder of the scribal and artistic achievements of early medieval England.

The physical dimensions of the Codex Amiatinus are staggering: standing nearly 20 inches tall, it contains 1,030 vellum leaves, each crafted from the hide of a calf. The immense tome weighs over 75 pounds, an extraordinary feat of material and labour that speaks to the resources and dedication of the Wearmouth-Jarrow scriptorium. The text, written in a clear and elegant uncial script, reflects the finest traditions of classical calligraphy, with a layout referred to as stichometric: a form of writing where sentences are divided into semantic units or phrases called cola (for longer phrases) and commata (for shorter phrases) to enhance readability, convey meaning, and even embody the rhythm and structure of spoken language. While this layout undoubtedly fails to make the most efficient use of parchment — each phrase (whether cola or commata) its rendered on own line — it has the effect of making prose read almost as though it were poetry. This arrangement was likely chosen in part to emulate Cassiodorus’s Codex Grandior, the now-lost model upon which the Codex Amiatinus was based. Taken together, all these features combine to help make this manuscript both a functional Bible and a visual embodiment of divine order, underscoring its dual purpose as a liturgical text and a devotional object.

The Codex Amiatinus is one of our best sources for St. Jerome’s Vulgate while also bearing witness to the broader cultural and textual currents of its time. The inclusion of Jerome’s prologues, prefaces, and capitula (chapter summaries) situates it within the exegetical tradition of late antiquity, while its alignment with Italian textual traditions reveals a deep connection between Anglo-Saxon England and Rome. The manuscript’s illuminations, notably the portrait of Ezra and the schematic plan of the Tabernacle, reflect Byzantine artistic influences, further emphasising the cosmopolitan nature of this Northumbrian masterpiece.

Significantly, the Codex Amiatinus represents not an isolated endeavour but the apex of a robust monastic scriptorium. Wearmouth-Jarrow produced three such pandects under Ceolfrid’s leadership, showcasing the intellectual and material resources of the community. This monumental Bible embodies the spirit of early medieval monasticism, where the labour of creating books was an act of worship, and the written word served as a bridge between the earthly and the divine. Its journey from Northumbria to Rome and, ultimately, to Florence underscores its legacy as one of the most noteworthy survivals of the medieval world.

❧ Charlemagne and the Quest for a Purer Bible

Not all bibles of the period were as remarkable as the Codex Amiatinus for textual accuracy. In the late eighth and early ninth centuries, the Carolingian Empire, under Charlemagne’s rule, faced a proliferation of divergent and often flawed manuscripts of the Vulgate Bible. Over the centuries errors had crept into many copies, ranging from simple transcription mistakes to more significant alterations in punctuation, word order, and even doctrinal phrasing. Recognising the necessity of a standardised and accurate biblical text to underpin both liturgical practices and theological education, Charlemagne initiated a comprehensive effort to restore the integrity of Jerome’s Vulgate. This endeavour was a cornerstone of the Carolingian Renaissance—a cultural revival aimed at unifying and strengthening the Christian identity of the empire through learning, order, and piety. The correction of biblical texts was explicitly mandated in Charlemagne’s Admonitio Generalis of 789, which declared that “faulty books” undermined proper worship and urged the clergy to “correct carefully” the sacred Scriptures.

Central to this mission was Alcuin of York, a scholar whose encyclopaedic knowledge of classical texts, mastery of Latin rhetoric, and theological insight set him apart as one of the leading intellectuals of his age. Recognising his rare ability to synthesise classical learning with Christian doctrine, Charlemagne invited Alcuin to lead the Palace School at Aachen, where he became a pivotal figure in advancing religious and cultural reforms. Around 796, Alcuin was appointed abbot of the prestigious Abbey of Saint Martin in Tours, where he oversaw one of the most influential scriptoria of the medieval world. From this scriptorium, Alcuin directed the production of his revised Vulgate Bible, which he presented to Charlemagne in 800 — the very same year he was crowned Holy Roman Emperor. The massive Moutier-Grandval Bible, now housed in the British Library, is a truly remarkable survival of Alcuin’s scriptorium. This Bible, likely an export to the monastery of Moutier-Grandval in the diocese of Basel, exemplifies the elegance and clarity of the Tours scriptoria under Alcuin’s leadership. Its inclusion of four full-page narrative miniatures, some of the earliest examples of such art in the Middle Ages, highlights the blending of textual reform and artistic innovation during this period.

The Moutier-Grandval Bible reflects Alcuin’s commitment to textual clarity and liturgical utility. The manuscript’s clear and legible Caroline minuscule script, a hallmark of the Tours scriptorium, made the text more accessible and reliable for readers. Its artistic programme, though modest by later medieval standards, emphasises the didactic and devotional purposes of the manuscript, illustrating key biblical narratives to complement the textual revisions. This combination of textual precision and visual sophistication underscores Alcuin’s holistic approach to biblical reform: uniting theological scholarship, textual integrity, and artistic expression to elevate the role of Scripture in the life of the Church.

While Alcuin’s revision focused on producing a clear and consistent text for widespread use, another prominent figure of the Carolingian Renaissance, Theodulf of Orléans, embarked on a more critical and scholarly approach to biblical correction. Theodulf, a bishop and intellectual closely associated with Charlemagne’s court, sought not only to eliminate textual corruption but to engage in a rigorous process of comparison and annotation. Drawing on various Latin exemplars and consulting Hebrew sources where possible, Theodulf produced what are now known as the Theodulf Bibles. These manuscripts, six of which survive today, are distinguished by their detailed marginal annotations, which document corrections and alternate readings. Unlike the liturgical focus of Alcuin’s revision, Theodulf’s Bibles were designed for close scholarly reading and textual study. Their use of a diminutive Caroline minuscule script allowed for a compact format, and their modest decoration underscored their function as practical tools for scholarship rather than ceremonial objects.

The combined efforts of Alcuin and Theodulf represent complementary facets of the Carolingian quest to standardise the biblical text. Alcuin’s work, rooted in the scriptorium of Tours, ensured a consistent and reliable version of the Vulgate for liturgical and educational purposes while Theodulf’s critical editions inaugurated a tradition of textual scholarship that anticipated the critical revisions scholars undertook in the Renaissance. Together, these efforts addressed the empire’s need for a coherent theological foundation, reinforcing its cultural and spiritual unity. By restoring the Bible’s textual integrity and enhancing its material presentation, Charlemagne’s court set out to safeguard the Scriptural heritage of Western Christendom while also reinforcing the Bible’s role as the bedrock of intellectual and spiritual life.

❧ Paris Bibles and the Rise of the Portable Pandect

By the thirteenth century, the Bible had undergone yet another transformation, this time shaped by the intellectual dynamism of the High Middle Ages. The rise of universities, particularly in Paris, created a demand for standardised, portable bibles suited to the needs of scholars, clergy, and mendicant preachers. Enter the Paris Bible, a compact, single-volume codex that revolutionised the relationship between the book and its user. For the first time, the Bible became a book that could be owned by an individual — a significant departure from the massive pandects of earlier centuries.

Paris Bibles introduced several innovations that are now taken for granted. They standardised the biblical text, placed biblical books in a consistent and regular order, and divided each book into chapters — a method for presenting the text that persists to this day. In addition, these bibles often included prologues and glosses to aid interpretation, reflecting the scholastic environment in which they were produced.

The production of Paris Bibles was driven by commercial scriptoria rather than monastic ones, marking a shift in manuscript culture. Such bibles were produced for a market rather than for a specific individual. This was possible in large part because of rising literacy rates among the urban laity as well as the pastoral missions of the Franciscans and Dominicans. While many Paris Bibles were functional, others were luxuriously illuminated, suggesting a diverse audience that ranged from itinerant friars to wealthy nobles.

The sheer number of surviving Paris Bibles — over six hundred were catalogued by Josephine Case Schnurman in 1960 — speaks to their ubiquity. Typically less than eight inches in height, these compact volumes were made possible by extraordinary advances in parchment production, with pages shaved thin or split to achieve an almost translucent quality. This, together with the use of compressed Gothic script and condensed page layouts, allowed for the entire biblical text to be contained in a single convenient volume.

The Paris Bible’s influence was felt far beyond its city of origin. A sample of thirteenth-century bibles from collections across Europe shows how widespread the Paris format became, with many adopting its textual order, prologues, and chapter divisions. While not every Bible was a strict copy of the Paris exemplar, a remarkable degree of uniformity emerged. This uniformity reflects the flourishing book trade of the period and the increased demand for consistent, reliable texts — particularly among the mendicant orders, who prized these bibles as perfect companions for their itinerant preaching.

The Paris Bible was not an official or singular standard, but its features — modern chapters, textual consistency, and portability — resonated deeply with the needs of the time. In Paris and beyond, it came to define the way Scripture was studied, taught, and lived. From the bustling scriptoria of Paris to the hands of wandering friars and noble patrons, the Paris Bible encapsulated the intellectual and spiritual currents of its age, embodying the ingenuity and ambition of a civilisation intent on making the Word of God both accessible and indispensable.

❧ Legacy

The history of the Latin Bible before Gutenberg was one of adaptation and innovation. From Jerome’s meticulous translations to the monumental Codex Amiatinus and the widespread use of Paris Bibles, each stage reflects the changing needs and aspirations of Western Christendom. By the mid-fifteenth century, the stage was set for a sweeping technological and cultural revolution. But Gutenberg’s press did more than usher in a radically new method for producing the Bible — it also set in motion a series of events that would change the face of Christianity forever. And yet, despite the undeniable importance of that moment in Mainz, it would be wrong to forget the countless (and mostly anonymous) scholars, monks, and scribes who ensured the survival and transformation of the Latin Bible throughout the previous centuries. Their work remains the bedrock upon which the modern Bible rests.

❧ Further Reading

- Charles, Sara J. The Medieval Scriptorium: Making Books in the Middle Ages. Reaktion Books, 2024.

- de Hamel, Christopher. “The Codex Amiatinus.” Meeting with Remarkable Manuscripts: Twelve Journeys into the Medieval World, Penguin, 2017, pp. 54–95.

- Light, Laura. “The Bible and the Individual: The Thirteenth-Century Paris Bible.” The Practice of the Bible in the Middle Ages: Production, Reception, and Performance in Western Christianity, edited by Susan Boynton and Diane J. Reilly, Columbia University Press, 2011, pp. 228–246.

- Williams, Megan Hale. The Monk and the Book: Jerome and the Making of Christian Scholarship. University of Chicago Press, 2006.