It is the summer of 1510, and the presses of Lyon are groaning.

In the Rue Mercière, printers and booksellers crowd the narrow streets. Beneath the clatter of type and the rhythm of the screw press, a quieter transformation is underway. Jacques Mareschal, a printer of measured ambition and steady hand, has just completed the final sheets of a book that will mark his entrance into one of the most saturated and competitive corners of the early modern book trade: the Latin Bible.

His Biblia cum pleno apparatu summariorum concordantiarum, issued in octavo, was not the first of its kind, nor would it be the last. But it was something notable—a compact, portable edition, printed for the bookseller Simon Vincent, and designed not only for liturgical or academic use, but for possession. It is dense with text, carefully typeset in a clear Rotunda type (a style of Gothic or Blackletter identified later by bibliographers as Rot37), and outfitted with marginal apparatus, chapter rubrics, and Jerome’s Index to Hebrew Names. In its final leaves, readers found a curious innovation: a mnemonic poem, composed in rhymed Latin quatrains, offering a summary of every biblical chapter — the Compendiolum Totius Sacrae Scripturae. The poem, attributed to a Franciscan friar named Franciscus Gotthi (or François Le Goust), was and remains a quiet marvel of compression and pedagogical flair. It was not Mareschal’s invention, but it is he who first gave it typographical form.

This Bible was no one-off venture. Over the next sixteen years, Mareschal returned again and again to the Latin Scriptures, issuing further octavo editions in 1514, 1517, 1519, and finally 1526—each slightly more ornate than the last. But the Bible was just one thread in a larger fabric. From at least 1509 to the late 1520s, Mareschal printed dozens of titles in a range of formats, working not only with Vincent but with other major Lyonnais booksellers including François Fradin, Antoine Du Ry, and the Compagnie des Cinq Plaies. Legal texts, theological treatises, classical commentaries, and medical compendia flowed from his shop, in quarto, folio, and octavo alike. He was not a specialist, but a generalist of high competence—a shop printer at the heart of Lyon’s collaborative book economy.

The city itself was fertile ground. Its biannual fairs drew buyers from across Europe, and its printers—working with shared types, common woodblocks, and overlapping client lists—operated as a networked guild of tradesmen. Within this matrix, Mareschal became known as a reliable craftsman. He favoured clarity over ornament, but his work showed care and typographic discipline. His Bible editions fit seamlessly into this world: functional, accurate, and commercially viable.

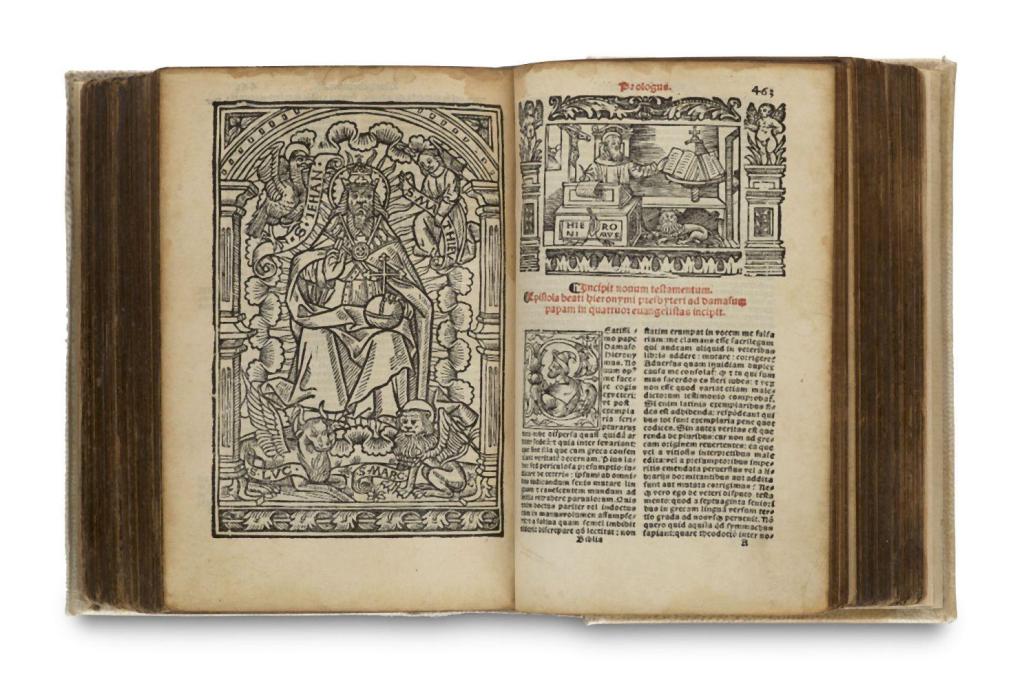

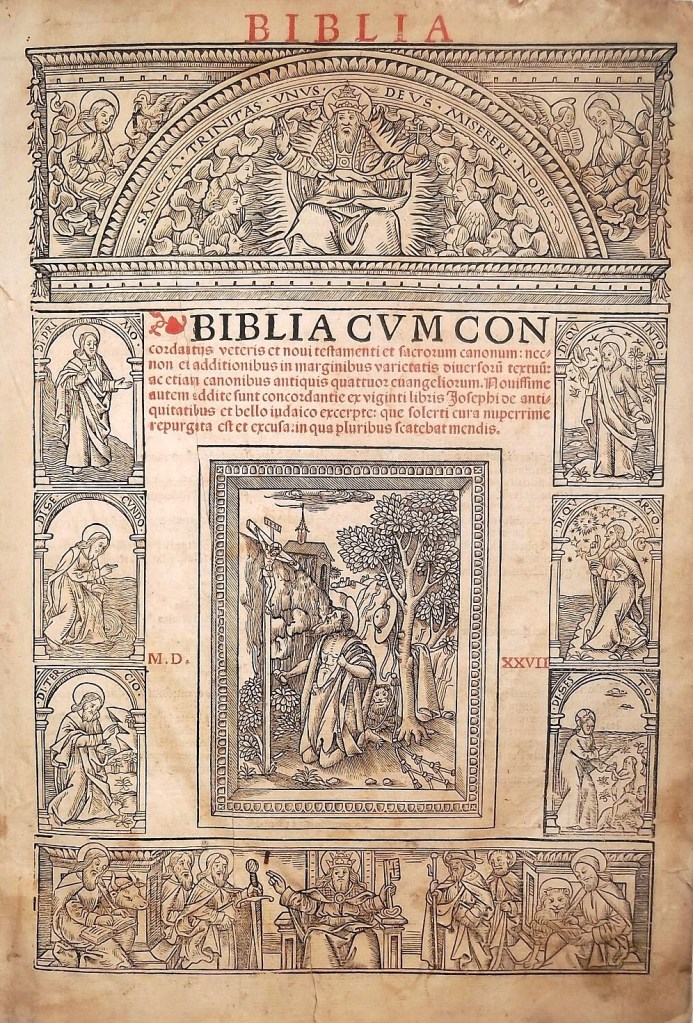

As a printer with a widely varied printing program, it should come as no surprise that he did not confine his Bible output to octavos alone. The same year he printed his first octavo Bible, 1510, Mareschal completed a monumental multi-volume folio Bible—this one accompanied by the Glossa ordinaria and the Postillae of Nicholas of Lyra. The tradition was venerable, reaching back to the great Latin Bibles of Anton Koberger and others—Mareschal’s edition, however, was largely derivative and seems to have been a commercial failure. A second edition never appeared (it survives today in only seven institutional copies or partial copies). But that didn’t mean he gave up on folios. In the wake of the enormous success of the Sacon/Koberger illustrated Latin Bibles, Mareschal set his sights on producing his own series of illustrated folio Latin Bibles. Beginning in 1523, these stately volumes, borrowing directly from the Sacond/Koberger illustrative program, began to appear on the market. Sometimes marketed under the title Biblia Magna, these Bibles undoubtedly met with eager buyers. Subsequent editions followed in 1525, 1526, and 1527. Today, these Mareschal folios remain some of the most beautiful Bibles to survive in relatively significant numbers from the period.

By the close of the 1520s, Mareschal’s name begins to fade from colophons. Whether through death, retirement, or shifting fortunes, one cannot say. Lyon continues on without him: the presses keep turning, and the Bible remained in demand. But for a time, in the first quarter of the sixteenth century, Jacques Mareschal stood among the great Bible printers of Lyon. Neither the first nor the most celebrated, he was a steady and prolific craftsman, deeply enmeshed in a trade that required not only skill and capital, but trust, adaptability, and a quiet ability to meet the needs of both collaborators and readers.