In the final quarter of the fifteenth century, the book world had a capital, and it was Nuremberg. From a tall house just beneath the castle walls, its windows framed by stone and its presses straining from dawn until dusk, Anton Koberger directed the most formidable printing enterprise in Europe. By the time of his death in 1513, his name would appear in the colophons of over two hundred works, ranging from theological summae to vernacular chronicles, from canon law to saints’ lives. Yet no part of his output was more sustained—or more significant—than his long and varied engagement with the Latin Bible. Between 1475 and 1522, Koberger either published or co-published at least twenty-five distinct editions, more than any other printer of his time. His imprint—alone or in partnership—can be found on nearly fifteen percent of all Latin Bibles printed in Europe before 1530. That his press continued to issue Bibles for nearly a decade after his death speaks to the institutional reach of his business and the enduring centrality of Scripture to his publishing vision. More than any of his contemporaries, Koberger helped define what a printed Bible could be.

The story of his Bibles begins, fittingly, with a series of majestic folios—large-format editions designed not only for liturgical use but also to astonish. The first appeared in 1475 (no. 18) and was followed by a rapid succession of reissues in 1477, 1478, 1479, and beyond (nos. 29, 32, 35, 39). Far from being austere or utilitarian, these Bibles were masterpieces of early printing: crisp in impression, spacious in layout, and frequently enhanced with lavish rubrication and hand illumination. Indeed, apart from the Gutenberg Bible (no. 1) and the 1462 Fust and Schoeffer edition (no. 4), there are no Latin Bibles from this period more imposing or beautiful. In fact, Koberger used the 1462 edition as a typographic model for his earliest efforts, subtly adapting layout to create something at once familiar and refined. Many surviving copies bear the marks of contemporary artists at work—opening initials adorned in burnished gold and lapis blue, ornamental flourishes in crimson and green, with bezants glinting in the margins. These were Bibles meant to be read, yes—but also to be revered. That Koberger could produce such volumes with such regularity speaks not merely to his technical command, but to his aesthetic ambition and instinct for grandeur.

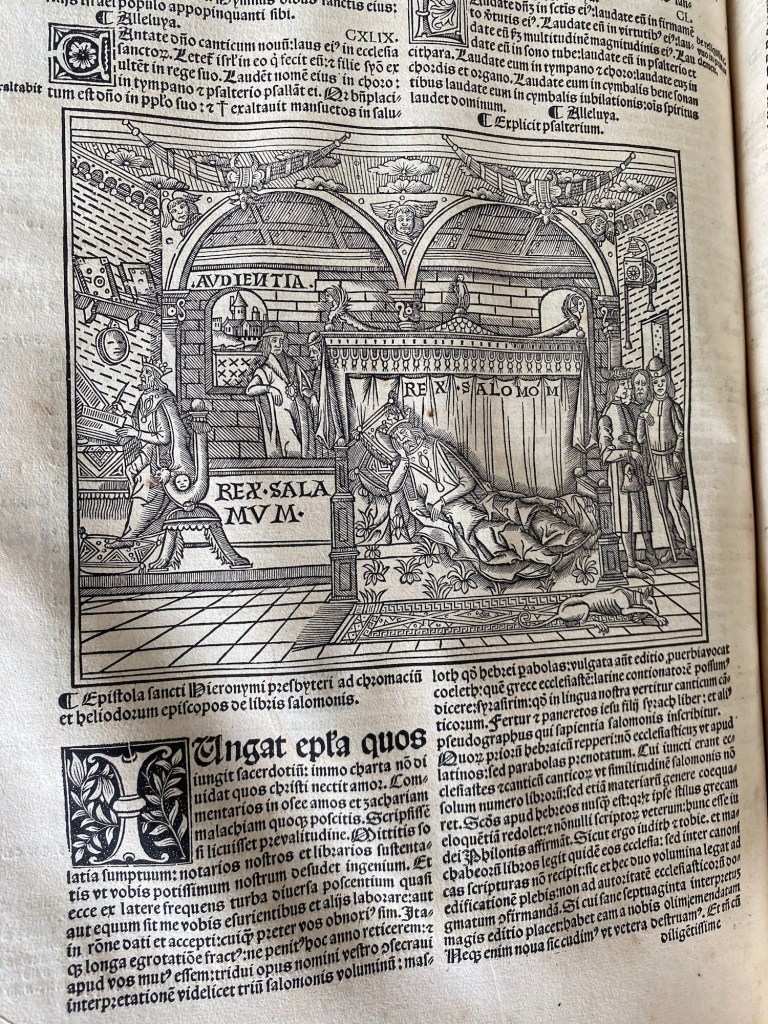

But Koberger was no purveyor of Bibles-as-usual. In 1485, he issued a monumental four-volume edition of the Latin Bible incorporating Lyra’s Postillae, along with thirty-eight woodcut illustrations—drawn from a separate suite of images Koberger had previously commissioned (no. 61). This 1485 Bible holds the distinction of being the first Latin Bible ever printed with woodcuts. Yet the images themselves are revealing. Rather than narrative scenes drawn from Scripture, they are largely diagrammatic: schematic renderings of tabernacles and temples, Aaron’s vestments, the vision of Ezekiel’s temple. They serve not to decorate but to explicate—to visualise the interpretive frameworks of Lyra’s commentary and provide the reader with tools for structured understanding rather than devotional contemplation.

That distinction is key. Although Koberger would go on to publish a stunningly illustrated German Bible in 1483—lavishly outfitted with 109 new woodcuts—he never repurposed those images for his Latin editions. The Latin Bible, in his conception, served a different audience with different expectations. It was not meant to charm the eye but to train the mind. His illustrated de Lyra Bibles (in 1485, 1486–87, 1493, and 1497) are thus best seen not as “illustrated Bibles” but as Bibles with illustrations—and those mainly in service to commentary and clarity.

And yet Koberger did eventually embrace the visual more fully. In the last years of his life, he entered into remarkable partnership with the Lyon-based printer Jacques Sacon, and together they produced a celebrated sequence of eight folio Latin Bibles between 1512 and 1522. The 1512 edition introduced woodcut illustrations clearly indebted to Giunta’s 1511 quarto (nos. 115, 113). Subsequent reissues in 1513 and 1515 followed the same format (nos. 118, 122), but from 1516 onward, Koberger’s heirs and Sacon began to experiment. They introduced references to Josephus, expanded the scholarly apparatus, and, in 1519, unveiled an entirely new cycle of woodcuts—some plausibly linked to the Dürer school (nos. 124, 128). These editions responded to a market that had grown both visually and intellectually ambitious, and they set a standard that reverberated through the pressrooms of France and the Empire.

Through it all, Koberger remained not just a printer, but a strategic publisher: managing partnerships, commissioning artists, overseeing distribution networks that stretched from Paris to Venice. His reputation was such that later chroniclers claimed he operated twenty-four presses and employed more than a hundred workmen—figures probably exaggerated, but not wildly so. His house was a place where books were born in industrial quantities, but also with a kind of gravitas. He understood that the Latin Bible was not just a religious text but a pillar of European learning, and he printed it accordingly.

Even after his death in 1513, the work continued. His name appears in colophons as late as 1522, and the editions he helped shape remained in circulation for years. Anton Koberger may be remembered best for the Nuremberg Chronicle, but his true legacy lies in the pages of the Latin Bible—printed with care, ambition, and a clarity of purpose that helped shape the very idea of what the printed Scriptures could be.