❧ Introduction

Lucantonio Giunta (1457–1538) occupies a singular place in the history of Venetian Renaissance printing. Born into a Florentine family that traced its roots to the thirteenth century, Giunta was one of seven children of Giunta di Biagio. While most of his family members remained in Florence, Lucantonio relocated to Venice in 1477, joining his brother Bernardo in the paper trade. Within a decade he had moved decisively into the world of publishing. By 1500 he had opened his own printing house, which over the next four decades produced more than four hundred of titles. When Giunta died in April 1538, he was recognised as having built not only one of the largest publishing houses in Renaissance Europe but also one of the most far-reaching, with a family network stretching from Florence and Lyon to Spain, Portugal, and Germany.

Giunta styled himself consistently as “Luc’Antonio Giunta fiorentino,” signalling both his loyalty to his city of birth and his awareness that Florence’s reputation for artistic and mercantile sophistication lent weight to his brand. His marriage in 1491 to Francesca di Soldano, a member of an old Florentine family, further reinforced this identity. Yet it was in Venice, the beating heart of European printing in the early sixteenth century, that he made his fortune. He began with devotional works such as the Imitatio Christi and a vernacular life of St Jerome, but his ambitions soon extended into the most demanding areas of liturgical, theological, legal, and classical publishing.

Unlike some of his contemporaries—Aldus Manutius being the most famous—Giunta did not present himself as a philologist-printer. He was not known for introducing Greek typefaces, nor did he pursue the dream of scholarly editions of the classics with the same humanist passion. Instead, his genius lay in scale, distribution, and illustration. He was an industrialist before the word had currency, grasping the power of networks, the value of visual appeal, and the profits to be had from the large clerical market. Missals, breviaries, graduals, and books of hours poured from his press, often in great folio formats, printed in red and black, and sometimes interlaced with musical notation. These demanded enormous capital outlays but promised steady sales, particularly as the Catholic liturgy underwent reform and standardisation. Giunta proved himself master of this field, and his publications were admired for their quality and sumptuous illustration.

❧ Giunta’s Latin Bibles

Within this larger output, however, two publications stand apart: his Latin bibles of 1511 and 1519. These are the only Latin bibles, containing both the Old and the New Testaments, that he ever published. Together they represent the culmination of decades of experimentation with illustrated texts. That they are a quarto and an octavo—and that he never printed a folio Bible—is a puzzle that requires explanation. But before turning to that question, it is necessary to appreciate the remarkable story of how these two editions came to be.

The story begins with the Italian Bible translated by Niccolò Malermi, first printed in Venice in 1471. This was the first Bible printed in Italian, and though the translation was stiff and at times inelegant, it proved extraordinarily popular. By the 1490s Giunta had become the leading publisher of the Malermi Bible. His editions of 1490, 1492, and 1494 were celebrated not only for their vernacular text but also for their woodcut programme, numbering more than three hundred images. These were not diagrammatic illustrations in the style of the German tradition (such as Koberger’s woodcuts for Lyra’s Postilla), but lively narrative cuts, attributed to the so-called Pico Master, that sought to make the stories of Scripture vivid to a wide audience.

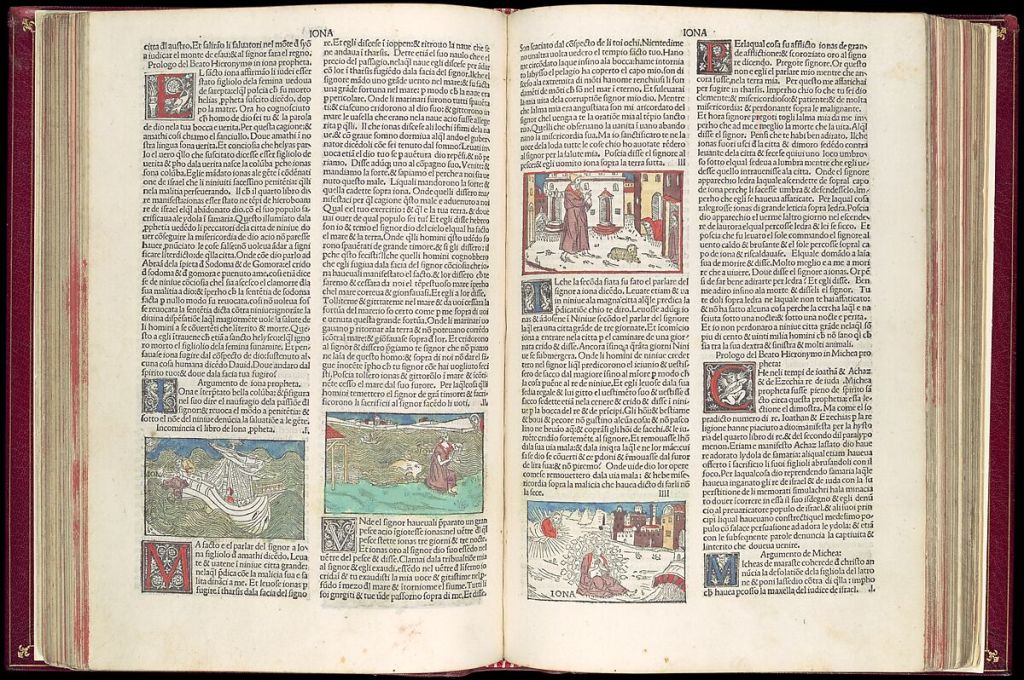

Giunta’s Malermi Bible (Metropolitan Museum of Art) with hand-coloured woodcuts.

In 1498, Giunta lent these very blocks—or a selection of them—to the printer Simon Bevilaqua, who used them in an ambitious quarto Latin Bible. Bevilaqua’s edition is a landmark: it was the first Latin Bible with narrative woodcuts, seventy-one in all, plus a few larger special images, including a memorable full-page creation scene. But Bevilaqua economised drastically. He used only a fraction of the hundreds of blocks at his disposal, and, curiously, he omitted illustrations from Genesis altogether. Whether he rented the blocks piecemeal from Giunta, or whether he judged the market too limited to justify the expense of fuller illustration, remains uncertain. In any case, Bevilaqua’s edition, though influential, appears to have sold sluggishly.

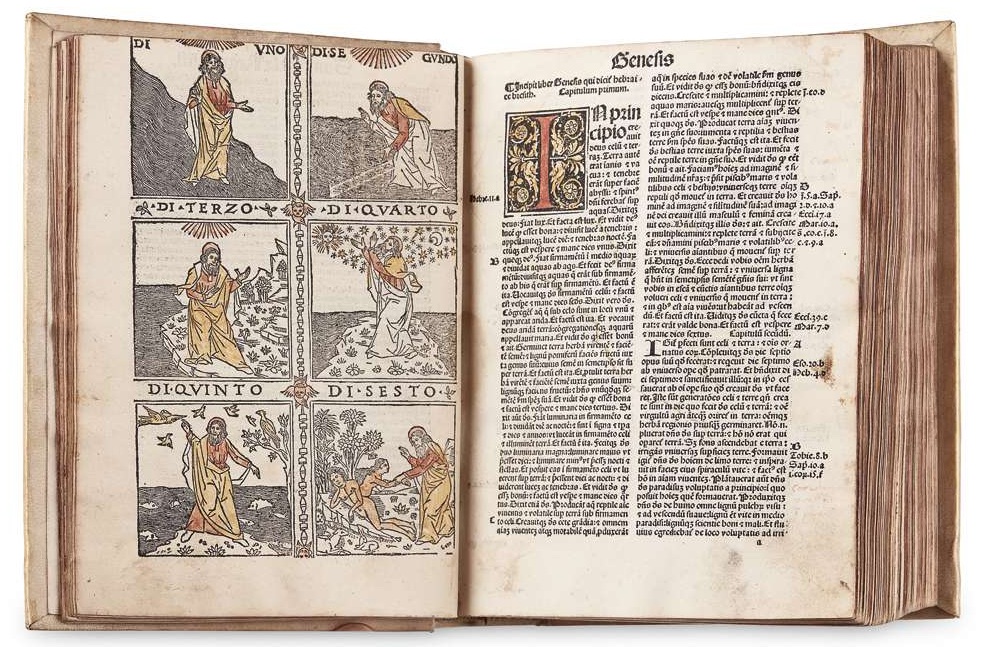

Bevilaqua’s 1498 illustrated Latin Bible open at the beginning of Genesis

❧ The 1511 Quarto

Giunta was watching closely. More than a decade later, in 1511, he judged the time ripe to risk his own illustrated Latin Bible. The result was extraordinary. His quarto Bible of that year contained 145 woodcuts, twice Bevilaqua’s number, and returned Genesis to pride of place. It also included the Eusebian Gospel Canons—an apparatus that had not appeared in a Latin Bible since the 1480s. The text was the Vulgate in the edition of Alberto Castellano, first published in 1504. Parts of the text were printed in red and black, further enhancing its visual splendour.

Giunta’s 1511 Latin Bible open at the beginning of Genesis

The timing was perfect. By 1511 Giunta had consolidated his distribution networks across Europe. His family members and associates traded his books in Spain, France, Portugal, and the Low Countries, and he was preparing to open his celebrated Lyon branch. The 1511 Bible, therefore, spread widely, and its illustrations were copied tirelessly, especially in Lyon, where they became the standard iconographic repertoire for generations of bibles. Not until the Treschsel brothers commissioned Hans Holbein for their great 1538 Latin Bible did the iconography of the illustrated Bible advance significantly beyond Giunta’s model.

Yet for all its brilliance, the 1511 Bible was not flawless. The woodblocks, already more than twenty years old, showed signs of wear. In the diagram illustrating Ezekiel’s vision—an image of particular exegetical subtlety—half the word secundum (in the phrase secundum Latinos) had become garbled. Later printers, inheriting this damaged block, misread the word altogether, so that in some Lyon editions secundum appears as mundum, rendering the image nearly unintelligible. Such accidents reveal both the durability and the fragility of Renaissance woodcut illustration: a single worn line could distort theological meaning for decades to come.

❧ The 1519 Octavo

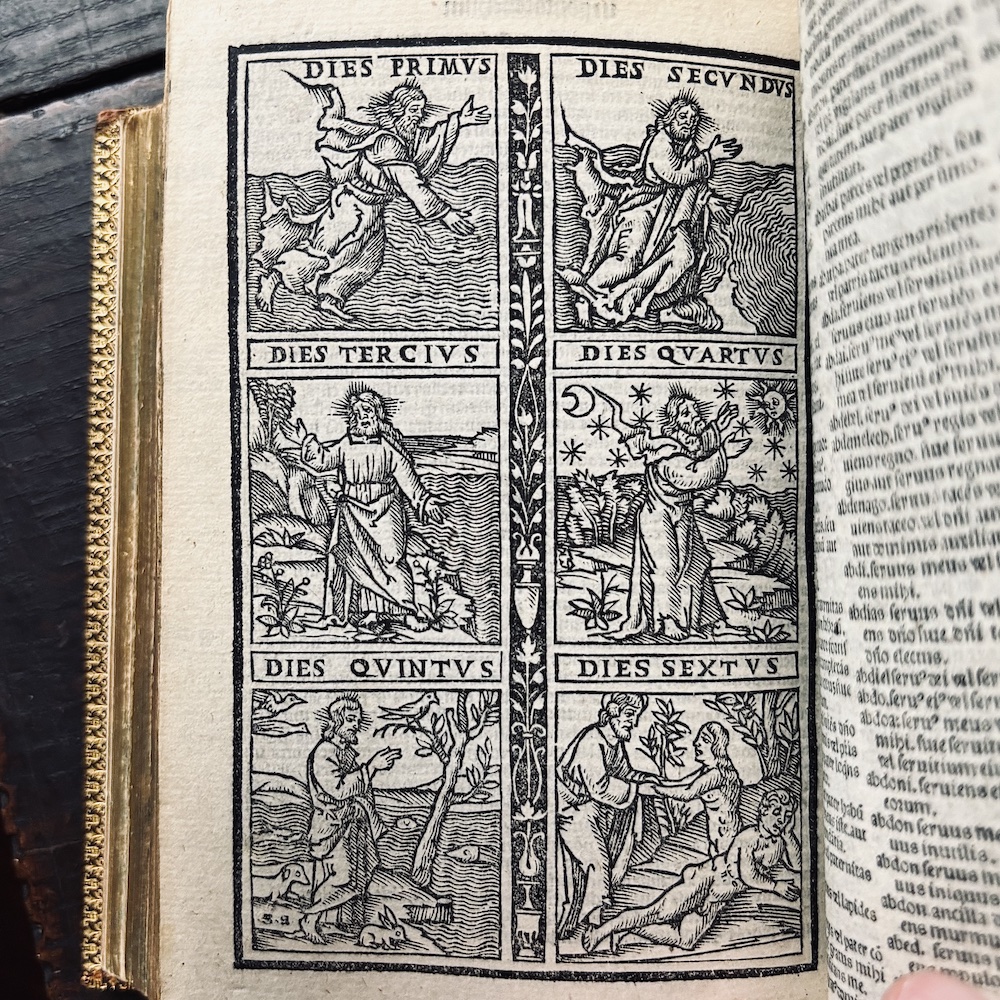

If the 1511 quarto was groundbreaking, Giunta’s 1519 octavo was dazzling. This was his second and last Latin Bible, and it coincided with an explosion of interest in portable “pocket” editions of the Scriptures. The year 1519 alone saw octavo bibles published by Jacques Mareschal, Jacques Sacon (both in Lyon), and by Jean Prevel and Jean Clereret in Paris. But Giunta’s octavo outshone them all. Where others offered sparse or modest illustration, Giunta’s octavo boasted more than 200 woodcuts—indeed 212 in total, along with historiated initials and decorative borders. Many of these images were reduced or adapted from the 1511 quarto, but their profusion in a compact format was unprecedented.

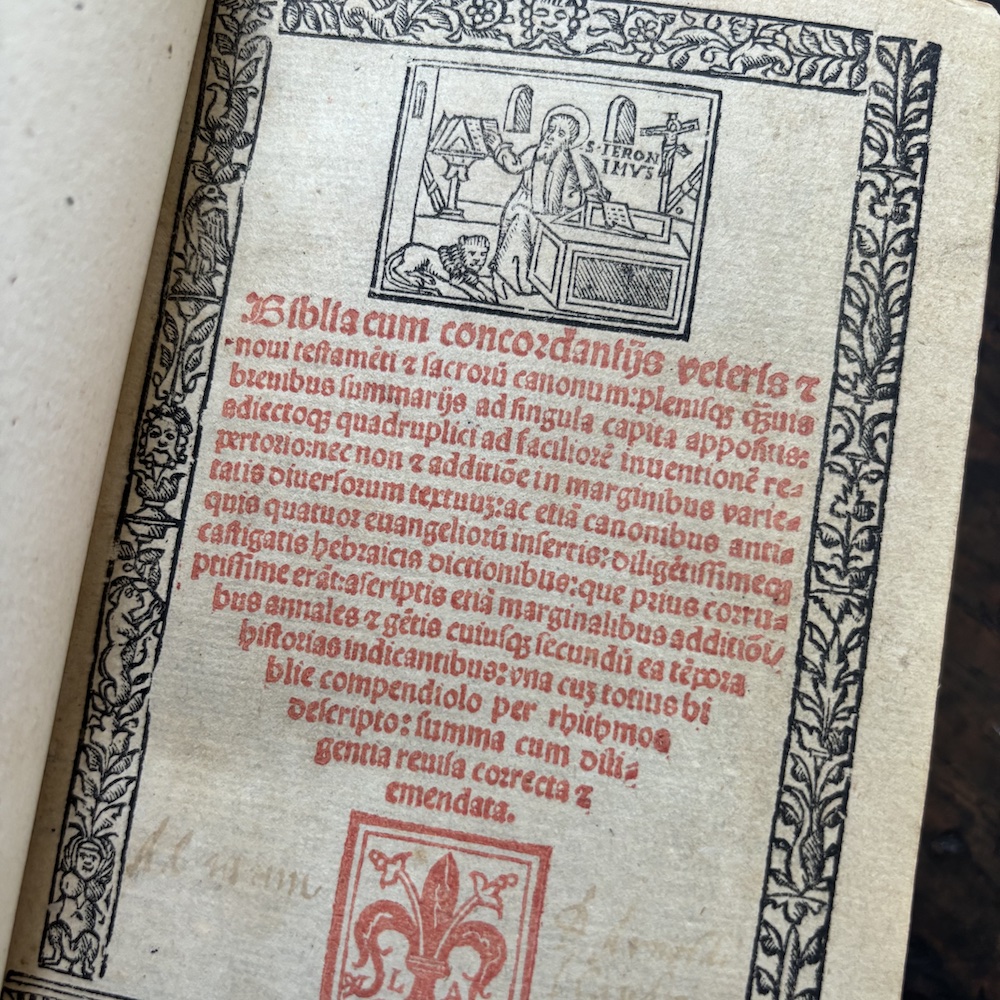

Giunta’s 1519 Latin Bible, title page (left) and Creation woodcut (right).

The 1519 octavo included two full-page cuts: the six days of Creation (repeated twice) and the Nativity, the former initialed Z.A. and attributed to Zoan Andrea Vavassore, a Venetian artist trained in the school of Andrea Mantegna. The title page, printed in red and black, framed both Jerome and Giunta’s familiar Florentine lily within a bold woodcut border. The text again followed Castellano’s Vulgate and the edition concluded with a remarkable poem (by 1519, a standard feature in octavo Latin bibles) by Franciscus Gotthi, a friar of the Franciscan order, who rendered the entire Bible into rhyming quatrains. Comprising over five hundred leaves, the volume was a tour de force of design, economy, and beauty. Among octavo Latin bibles of the early sixteenth century, it remains unrivalled.

❧ No Further Editions: Why?

What then are we to make of the fact that Giunta printed only these two Latin bibles—one quarto in 1511 and one octavo in 1519—and never a folio? The puzzle is striking, for his contemporaries in Lyon, Paris, and Basel issued folio bibles regularly. Folios commanded prestige, and their large pages offered room for elaborate paratexts, glosses, and illustrations. Giunta, after all, was not averse to folio publishing. His liturgical volumes were often monumental folios, sumptuously illustrated and handsomely printed. Why not a folio Bible?

One possibility is economic. Folio bibles were costly to produce and uncertain in market appeal. The clerical market demanded a seemingly endless supply of liturgical books, which Giunta could sell steadily. Latin bibles in folio, however, were luxury items with narrower demand. Perhaps he believed that the quarto offered a compromise: large enough to display illustration effectively, but economical enough to sell broadly. The 1511 quarto evidently proved successful, judging from the rapid diffusion of its iconography.

A second possibility is strategic. Giunta may have calculated that illustrated Latin bibles would succeed only if positioned as affordable and accessible. Folios would have signalled an elite scholarly or ecclesiastical audience. By issuing a quarto and later an octavo, Giunta may have sought to expand the Bible’s reach into the hands of merchants, parish priests, and educated lay readers who could afford a handsome but not exorbitant volume. In this sense, Giunta’s editions stand midway between the grand German tradition of Koberger and the compact “pocket” bibles that proliferated in the 1520s.

A third possibility is pragmatic. Giunta already had his hands full with folio liturgical books. Adding a folio Bible might have diverted capital and resources from his most profitable sector. Better to cede the folio Bible market to others while establishing his own dominance elsewhere.

The fact that he printed each only once raises similar questions. Was the 1511 quarto more influential than it proved to be commercially successful? Did the 1519 octavo face too much competition from rival presses, despite its obvious superiority, for a repeat venture to be profitable? Or was Giunta himself more interested in the novelty of entering the field than in sustaining it? We cannot know for certain. What is clear is that his two Latin bibles exerted an outsized influence, shaping expectations of readers for a generation.