❧ Anton Koberger and the Logic of Networks

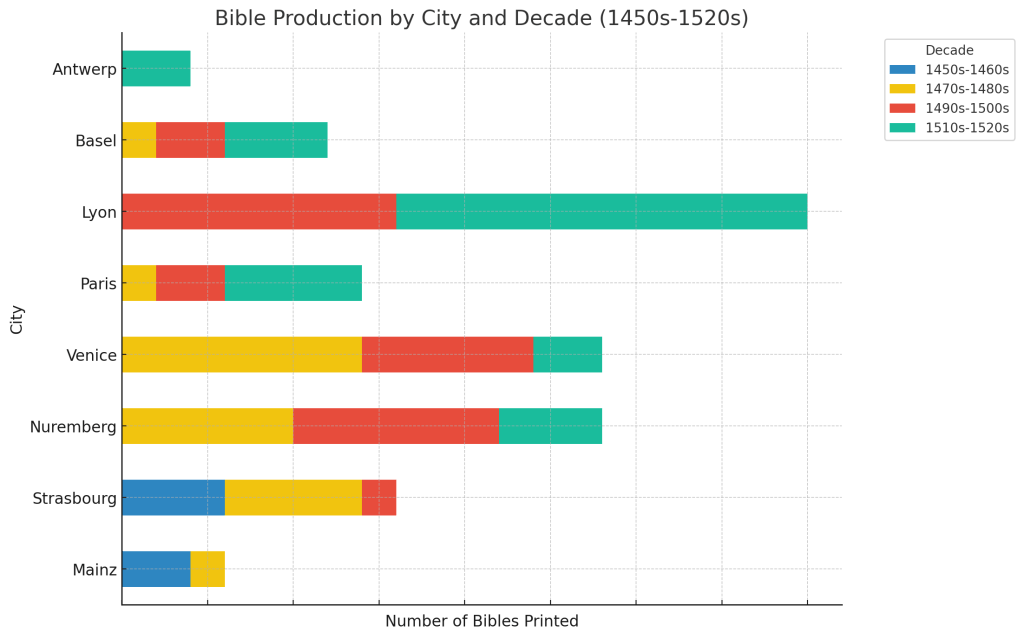

Mention early printed Bibles and the conversation almost invariably turns to Gutenberg. Yet if one surveys the nearly two hundred complete Latin Bible editions printed between 1455 and 1529, another name emerges as structurally more dominant across time: Anton Koberger of Nuremberg. Whether acting alone or in partnership, Koberger and his successors were responsible for nearly fifteen percent of all Latin Bibles printed in Europe before 1529. No other printer’s name appears in Bible colophons over such a sustained span. His first Latin Bible was issued in 1475, scarcely twenty years after the 42-line Bible; the last bearing his name appeared in 1522, almost a decade after his death.

This longevity was not accidental. Koberger’s workshop functioned both as a press and as a publishing enterprise whose reach extended beyond Nuremberg itself. He collaborated repeatedly with major figures across Europe — most notably Jacques Sacon in Lyon — and his capital and imprint travelled with those partnerships. Editions printed “expensis Anton Koberger” in French cities testify to a business model that transcended local production. What began as a Nuremberg operation became a trans-regional network, sustained by family succession, strategic alliances, and a recognisable brand.

Koberger’s career therefore provides a lens through which to view the broader Latin Bible market of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Production was not evenly distributed among dozens of isolated printers. Rather, it clustered around powerful houses that combined technical capacity, commercial acumen, and long-term collaboration. Jacques Mareschal’s prolific decade in Lyon between 1510 and 1519 — during which he issued eleven Latin Bible editions, often in partnership with Simon Vincent — illustrates a similar logic of concentrated output. Yet even here the contrast is instructive: whereas Koberger’s dominance rested largely on imposing folio editions designed for institutional buyers, many of Mareschal’s were compact octavos, almost certainly printed in larger runs to reach a different segment of the market.

The history of the Latin Bible before 1529 is thus not simply a story of printing spreading from city to city. It is a story of networks — of workshops that trained successors, of capital that crossed borders, of partnerships that consolidated markets, and of formats that evolved in response to competition. In this landscape, Anton Koberger stands as the clearest early example of how sustained collaboration and strategic publishing shaped the European Bible trade.

❧ Mainz as Catalyst: The Technical Diaspora

Mainz is where it all began. The 42-line Bible produced in the workshop of Johann Gutenberg, in partnership with Johann Fust and later Peter Schoeffer, did more than introduce moveable type to Europe. It established a model — technical, aesthetic, and economic — that others would carry outward. The large folio format, double-column layout, dense textura type, and rubricated finish together created a prestige template for what a printed Bible should be.

Yet Mainz did not remain the permanent centre of production. The political unrest of the early 1460s, including the sack of the city in 1462, likely accelerated the dispersal of trained printers. Whether as direct apprentices, collaborators, or simply craftsmen who had absorbed the new techniques, figures associated with the Rhineland rapidly began to establish presses elsewhere. Johann Mentelin in Strasbourg produced a Latin Bible not long after 1460, one of the earliest to follow the Mainz model. Heinrich Eggestein, also in Strasbourg, issued multiple folio Bibles during the 1460s and early 1470s, reinforcing the city’s role as a secondary centre of Bible production.

Bamberg’s 36-line Bible, printed by the so-called “Printer of the 36-line Bible,” reflects a similar transmission of technique, closely echoing Mainz typographical forms. In Cologne, printers such as Conrad Winters and Nicolaus Götz sustained folio Bible production in the 1470s. Basel, too, entered the field early, with Berthold Ruppel — himself often associated with Gutenberg’s circle — producing a Latin Bible by about 1468, followed by another Latin Bible in 1474 with the cooperation with Bernhard Richel. Late that same decade, Johann Amerbach published his own folio Latin Bible in Basel.

What is striking about this first generation of printers is their relative uniformity of ambition. Nearly all of these editions were substantial folios, designed for ecclesiastical or institutional buyers. The technical craft — from casting type and setting type to imposing formes — travelled with the printers, and with it travelled an understanding of the Bible as a monumental object. Although Mainz never became a major centre of Bible production by volume, it profoundly shaped how the Bible was understood as a material book. Its workshops functioned as training grounds, and the diaspora of its craftsmen established the first interconnected network of Bible presses across the German-speaking lands and beyond.

❧ Venice: Scale, Beauty, and Competitive Plurality

Venice presents us with a different model altogether: scale without singular dominance. From the mid-1470s onward, the lagoon city became one of Europe’s most prolific centres of book production–including production of the Latin Bible. Yet unlike Nuremberg under Koberger, Venice did not consolidate that production under one enduring house. Instead, it fostered a competitive plurality in which numerous printers entered the field, often issuing one or two editions before turning to other ventures.

Franciscus Renner and Nicolaus de Frankfordia were among the earliest Venetian producers of folio Latin Bibles in the 1470s, followed closely by Nicolaus Jenson, whose elegant roman types set new aesthetic standards. Leonardus Achates de Basilea and Johannes Herbort likewise contributed imposing folios during these years. By the close of the incunable period, Venice had come to excel not only in quantity but in visual refinement. The city’s presses produced some of the period’s most handsome Latin Bibles, including richly rubricated folios and, from 1480 onward, a steady if selective series of quartos, among them editions from the presses of Renner, Octavianus Scotus, Simon Bevilaqua, Johannes Herbort, and Georgius Arrivabenus. Although Venice did not invent the quarto format — the first quarto Latin Bible was printed at Piacenza in 1475 — Venetian printers adopted it energetically within Europe’s most export-oriented book market, presenting a portable and commercially viable alternative to the monumental folio. In 1492 Hieronymus de Paganinis went further still, issuing an octavo Latin Bible — only the second octavo Bible in the history of printing — and the first Bible to feature a woodcut on its title page.

Despite this obvious vitality, no single Venetian printer sustained long-term control of the Latin Bible market. Paganinus reissued his 1492 octavo in 1497, and Lucantonio Giunta entered the field in 1511 with a groundbreaking and influential illustrated quarto. Giunta printed the complete Latin Bible only once more — in 1519 — when he produced what was, up to that time, the most lavishly illustrated octavo yet issued. But at least in this one respect, both Paganinus and Giunta were entirely typical: most Venetian printers who undertook to print the Latin Bible did so only once or twice before turning to other projects. None achieved the multi-decade imprint continuity visible in Nuremberg under Koberger or later in Lyon. Venetian Bible production was therefore expansive rather than consolidated — commercially energetic, aesthetically ambitious, and responsive to format innovation, yet structurally plural.

❧ Basel: Editorial Experiment and Humanist Inflection

Innovation in the early Latin Bible trade was widely dispersed. Basel became a centre for Bible production in the 1460s, when Berthold Ruppel and Bernhard Richel issued substantial folios that followed the Mainz prestige model. Johann Amerbach’s 1479 Latin Bible was the first of the famous “fontibus ex Graecis,” editions, signalling a growing attentiveness to importance of returning to the original source languages. Though modest by later humanist standards, Amerbach’s Bible pointed toward a philological horizon that would become increasingly central throughout the sixteenth century.

In 1487 Nicolaus Kesler’s folio became the first Latin Bible to include the short preface Modi intelligendi sacram scripturam, an interpretive guide introducing readers to the four senses of Scripture relied upon by readers and exegetes throughout the Middle Ages. A few years later, in 1491, Johann Froben issued the first Latin Bible in octavo format. This compact edition not only altered scale; it incorporated references to parallel passages throughout and addressed lay readers directly in the new preface Ad divinarum litterarum amatores exhortatio. Thus the overall editorial program Basel was one clearly centred on treating the Bible as more than an object of reverence: it was also a tool for study and personal devotion. As a university city later associated with Erasmus and northern humanist scholarship, this orientation is hardly surprising.

By the early sixteenth century Basel had become one of the principal centres of learned printing in Europe, a city in which philological precision, textual comparison, and engagement with Greek and Hebrew sources were increasingly valued. Printers like Amerbach and Froben operated within a milieu attentive to correction and linguistic refinement. Their editions did not dominate the market numerically, but they responded to — and helped shape — a culture in which Scripture was to be examined and understood with scholarly discipline. In this sense Basel functioned less as a volume leader than as an intellectual laboratory: a place where the printed Latin Bible was quietly reframed for an age of humanist study.

❧ Lyon: Consolidation, Diversification, and Market Control

From roughly 1505 onward, the density of Latin Bible editions issuing from presses in Lyon is unmistakable. What had earlier been a significant but secondary centre became, within two decades, the dominant force in the Latin Bible trade. The pattern visible in the editions themselves — repeated names, recurring partnerships, and sustained output across multiple formats — reveals not sporadic participation but deliberate market control.

Jacques Sacon stands at the centre of this development. Beginning with substantial folio editions in 1506 and 1509, he established a serious presence in the market. After that he entered into a remarkably durable partnership with Anton Koberger (and his heirs) to produce a stunning series of illustrated folio Bibles with financial backing from Nuremberg. In addition, he also issued a number of smaller illustrated octavo bibles using his own resources. Few European printers matched such sustained activity in the same genre.

Alongside Sacon, Jacques Mareschal emerged as a complementary force. From 1510 onward he issued both imposing folios and, increasingly, compact octavos. Between 1510 and 1519 alone, Mareschal produced a remarkable cluster of editions, often in partnership with Simon Vincent. The octavo format proliferates here: 1510, 1514, 1517, 1519, and beyond. These smaller Bibles, dense with introductory materials, references, and marginal apparatus, were almost certainly printed in larger runs to ensure commercial viability given the lower unit price required to sustain octavo production.. The shift was not aesthetic but strategic. Lyonese printers were segmenting the market, offering monumental folios for institutional buyers while simultaneously supplying portable editions for students, clergy, and educated lay readers.

The network widened further through figures such as Étienne Gueynard, Jean de Moylin, Jean Marion, Jean Crespin, and later the Giunta partnerships in the 1520s. Editions printed or sold jointly across Lyon, Paris, and even Nuremberg underscore the increasingly interconnected nature of the trade. Titles grow longer and apparatus heavier — concordances, marginal variants, repertories, even excerpts from Josephus — signalling that competition was now occurring not only in format but in editorial enhancement.

By the early 1520s, Lyon’s presses were issuing folios, quartos, and octavos in rapid succession. The city no longer merely participated in the Latin Bible market; it defined it. Where Venice had been energetic but plural, and Basel intellectually distinctive but comparatively restrained in volume, Lyon combined sustained output, diversified formats, and strategic partnerships. In the final decade before 1529, it functioned as the principal powerhouse of Latin Bible production in Europe — a position achieved not by accident, but through calculated consolidation and commercial agility.

❧ The Maturation of the Printed Latin Bible

Across the entire corpus of complete Latin Bibles between 1455 and 1529, several structural patterns become clear. The earliest decades are dominated by monumental folios issuing from the Rhineland and Upper German cities, closely modelled on the Mainz prototype. The Bible first enters print as an object of institutional scale and visual authority. Yet from the 1470s onward, geographic centres multiply and formats diversify. Quarto experiments appear in Italy; glossed and illustrated editions expand the apparatus; Venetian presses explore portability; Basel introduces the octavo; Lyon later multiplies it.

At the same time, the paratext thickens. What begins as text with modest additions develops into lengthy introductions and prefaces, marginal and interlinear commentaries, references to historical and legal works, cross references, narrative and diagrammatic woodcuts, marginal variants, and increasingly explicit claims of correction against Greek and Hebrew sources. Titles lengthen as printers advertise their editorial labour. By the 1520s, the rhetoric of emendation, correction, and even retranslation signals that the Latin Bible has become not only a sacred book and commercial commodity, but also a contested text.

Production clusters around powerful houses and enduring partnerships rather than dispersing evenly. Workshops train successors; capital travels across borders; imprints outlive their founders. From Mainz’s technical diaspora to Koberger’s branded network, from Venice’s competitive plurality to Basel’s editorial inflection and Lyon’s consolidation, the history of the Latin Bible before 1529 reveals a market that matured rapidly in both scale and sophistication.

On the eve of the Reformation, the Latin Bible was no longer a single typographical marvel. It was a fully developed European industry — geographically dispersed, commercially competitive, textually self-aware, and increasingly attentive to its readers. The transformations that would soon follow did not emerge in a vacuum. They arose within a book trade already shaped by networks, experimentation, and strategic adaptation.

❧ Index of Printers and Publishers

of Latin bibles, 1455-1529

Anton Koberger (Nuremberg): 25 editions

Jacques Sacon (Lyon): 14 editions

Jacques Mareschal (Lyon): 11 editions

Johann Froben (Basel): 7 editions

Etienne Gueynard (Lyon): 6 editions

Johann Amerbach (Basel): 6 editions

Franciscus Renner (Venice): 5 editions

Bernhard Richel (Basel): 4 editions

Nicolaus Götz (Cologne): 4 editions

Jean Prevel (Paris): 4 editions

Theilman Kerver (Paris): 4 editions

Jacques Giunta (Lyon): 3 editions

Heinrich Eggestein (Strasbourg): 3 editions

Jean Marion (Lyon): 3 editions

Conrad Winters (Cologne): 3 editions

Nicolaus Jensen (Venice): 3 editions

Jean Crespin (Lyon): 3 editions

Nicolaus de Frankfordia (Venice): 3 editions

Simon Vincent (Lyon): 3 editions

Jean de Moylin (Lyon): 3 editions

Johann Fust (Mainz): 2 editions

Peter Schoeffer (Mainz): 2 editions

Berthold Ruppel (Basel): 2 editions

Johann Mentelin (Strasbourg): 2 editions

Leonardus Wild (Venice): 2 editions

Octavianus Scotus (Venice): 2 editions

Peter Drach (Speyer): 2 editions

Lucantonio Giunta (Venice): 2 editions

Johann Petreius (Nuremberg): 2 editions

Peter Quentel (Cologne): 2 editions

Antoine de Ry (Lyon): 2 editions

Robert Estienne (Paris): 2 editions

Nicolaus Kesler (Basel): 2 editions

Johannes Herbort (Venice): 2 editions

Johann Prüss (Strasbourg): 2 editions

Simon Bevilaqua (Venice): 2 editions

François Regnault (Paris): 2 editions

Pierre Regnault (Caen): 2 editions

Johann Koberger (Nuremberg): 2 editions

Hieronymus de Paganinis (Venice): 2 editions

Leonardus Achates (Basel): 1 edition

Michel Angier (Caen): 1 edition

Georgius Arrivabenus (Venice): 1 edition

Nicolas de Benedictis (Lyon): 1 edition

Angelus Britannicus and Jacobus Britannicus (Brescia): 1 edition

Dominici Berticinium (Lyon): 1 edition

Jean Clereret (Paris): 1 edition

Martin Crantz, Michael Friburger, and Ulrich Gering (Paris): 1 edition

Johannes Petrus de Ferratis (Piacenza): 1 edition

Vincent de Portonariis (Lyon): 1 edition

Johann Gutenberg (Mainz): 1 edition

Johann Grüninger (Strasbourg): 1 edition

Perrinus Lathomi (Lyon): 1 edition

Jean Macé (Rennes): 1 edition

Jacobus Maillet (Lyon): 1 edition

Mathias Moravus and Biagio Romero (Naples): 1 edition

Pierre Olivier (Rouen): 1 edition

Paganinus de Paganinis (Venice): 1 edition

Friedrich Peypus (Nuremberg): 1 edition

Philippe Pigouchet (Paris): 1 edition

Nicolaus Philippi and Marcus Reinhart (Lyon): 1 edition

The ‘R-printer’ (Strasbourg): 1 edition

Reynaldus de Novimagio and Theodorus de Reynsburch (Venice): 1 edition

Biagio Romero and Mathias Moravus (Naples): 1 edition

Adolf Rusch (Strasbourg): 1 edition

Johann Siber (Lyon): 1 edition

Printer of the 36-line Bible (Bamberg): 1 edition

Type of the 36-line Bible (Mainz): 1 edition

François Turchi (Lyon): 1 edition

Printer of Guido (Lyon): 1 edition

Simon Vostre (Paris): 1 edition

Michael Wenssler (Basel): 1 edition

Thomas Wolff (Basel): 1 edition

Heinrich Quentell (Cologne): 1 edition

Johann Zainer (Ulm): 1 edition