Biblical commentaries—whether glosses (from the Greek glōssa, meaning “tongue”) or postils (from the Latin post illa verba textus, “after these words of the text”)—were sometimes incorporated into Latin Bibles printed before 1530. When they were, it was never a neutral decision. Commentaries added significantly to the complexity of typesetting and increased the overall size, and cost, of the finished book. It has often been noted that Europe’s earliest printers, for all their technical daring, were cautious market actors. They tended to rely on well-established texts from the ancient and medieval worlds, betting that familiarity would translate into sales. The same conservatism shaped the choice of biblical commentaries. Printers who included them generally favoured works written centuries earlier rather than more recent or experimental exegesis. These commentaries took many forms, ranging from verse-by-verse explanation and thematic treatises to homilies and glosses, the latter often appearing as compact notes squeezed into margins or threaded between the lines of Scripture itself.

A close reading of this bibliography shows that a small group of commentators proved especially enduring. Works attributed to Walafrid Strabo, Anselm of Laon, Nicholas of Lyra, Paul of Burgos, Guillelmus Brito, and Matthias Döring recur with striking frequency. In many cases, a Bible that included one of these authorities included several more, creating dense layers of interpretation around the biblical text. What follows is a brief introduction to each of these figures, outlining their historical context and their contribution to the long tradition of biblical exegesis.

Walafrid Strabo (c. 808–849) was an influential figure of the Carolingian Renaissance, remembered as a poet, hagiographer, and theologian, and long associated with the tradition of biblical glossing. For centuries, he was commonly linked with the Glossa Ordinaria, a vast and influential body of marginal and interlinear commentary on Scripture. This association, however, reflects medieval habits of attribution rather than modern ideas of authorship. Strabo was not the compiler of the Glossa Ordinaria in any strict sense. Rather, the work emerged gradually in the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries, principally at the cathedral school of Laon, through the teaching activity of Anselm of Laon and his circle (see below). Drawing heavily on patristic authorities and earlier exegetical traditions, the Glossa developed as a pedagogical tool, designed to guide readers through the biblical text by surrounding it with layers of interpretation. In manuscript culture, the Glossa Ordinaria was not a fixed or uniform work. It existed as a flexible and evolving framework, with glosses added, adapted, or omitted according to local practice and teaching needs. Its authority lay not in single authorship but in long use. Over time, Scripture and gloss became so closely intertwined that, in academic contexts especially, the Bible without its commentary could appear incomplete. The transition to print transformed this living tradition. When early printers undertook the formidable task of producing the Glossa Ordinaria, they did more than reproduce a familiar aid to study: they stabilised and standardised a commentary that had previously been fluid. Despite the immense typographical complexity and expense involved, the Glossa Ordinaria appeared in roughly half a dozen Latin Bibles printed before 1530. The first of these was produced around 1480 in Strasbourg by Adolf Rusch for Anton Koberger (no. 47), a striking example of how even the most commercially cautious printers were willing, at times, to take extraordinary technical risks in service of a proven intellectual authority.

Anselm of Laon (d. 1117) was one of the most influential teachers of the early twelfth century and a central figure in the rise of the cathedral schools that transformed medieval biblical study. As master of the school at Laon, he helped pioneer a new, classroom-centred approach to Scripture, one that treated the biblical text as something to be analysed closely, line by line, rather than simply proclaimed or paraphrased. He is closely associated with the development of the Glossa Interlinearis, a form of commentary in which brief explanatory notes were written directly between the lines of the biblical text itself. These interlinear glosses were designed to clarify grammar, resolve apparent contradictions, and guide readers through difficult passages with minimal interruption to the flow of reading. The Glossa Interlinearis was not intended to stand alone. Almost from the beginning, it circulated alongside the Glossa Ordinaria, the two together forming a dense interpretive apparatus that framed Scripture on all sides. If the Ordinaria provided authoritative voices drawn from the Church Fathers and earlier exegetes, the Interlinearis supplied immediate, practical guidance for understanding the text at hand. Their combined use reflects the pedagogical culture of the schools, where Scripture was read slowly, analytically, and in constant dialogue with inherited interpretation. This pairing was carried into print with remarkable fidelity. Adolf Rusch’s Strasbourg Bible of around 1480—the first printed Bible to include the Glossa Ordinaria—was also the first to incorporate the Glossa Interlinearis (no. 47), effectively preserving in typographic form a mode of biblical study that had shaped theological education for nearly four centuries.

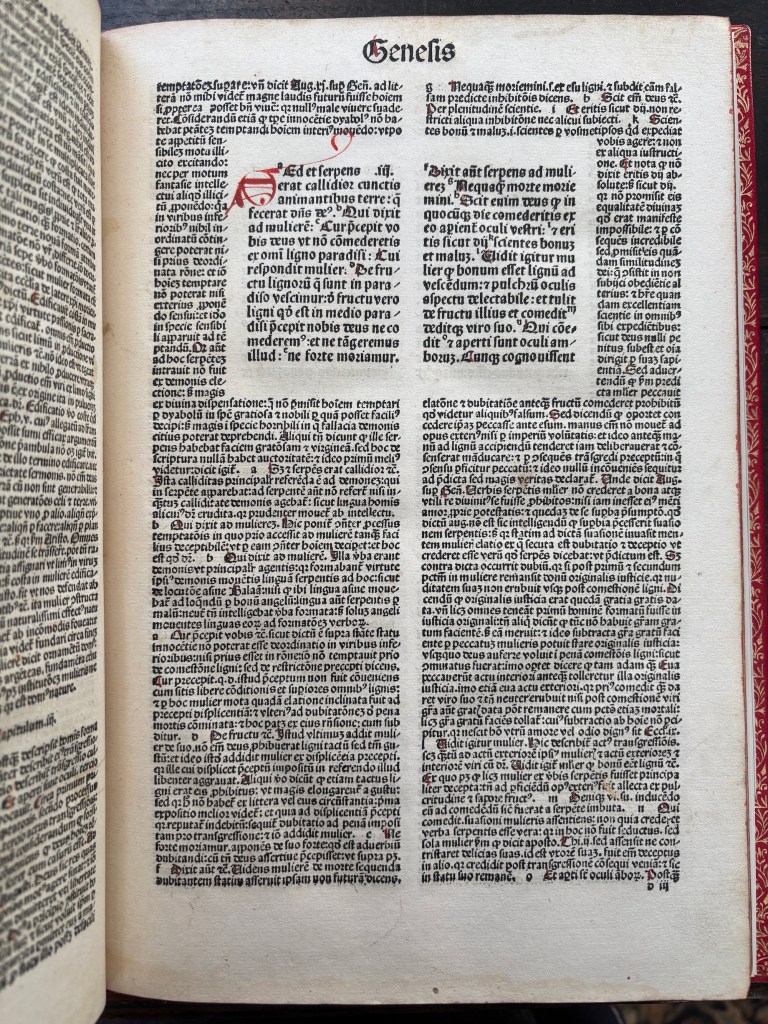

The Postillia of Nicholas of Lyra surrounding the Biblical text in Anton Koberger’s 1487 edition of the Latin Bible (Genesis 3:1-7).

Nicholas of Lyra (c. 1270–1349), a Franciscan friar born in Normandy, was among the most influential biblical exegetes of the later Middle Ages. Trained at the University of Paris, where he later became regent master of theology, Nicholas spent his entire academic career within the Parisian schools. Unlike most Christian scholars of his generation, he acquired a working knowledge of Hebrew and engaged directly with Jewish exegetical traditions. His writings show familiarity with the Talmud, Midrash, and, above all, the biblical commentaries of Solomon ben Isaac of Troyes, known as Rashi, whose influence on Nicholas’s method is unmistakable. Nicholas’s major work, the Postillae litteralis super totam Bibliam, completed in 1331, marked a decisive moment in the history of biblical interpretation. Rather than abandoning allegorical or spiritual readings, Nicholas insisted that they must rest upon a careful understanding of the literal and historical sense of the text. Scripture, he argued, could not mean spiritually what it did not first mean historically. This emphasis was both innovative and controversial in a culture long accustomed to allegorical elaboration, and it reshaped the way Scripture was read, taught, and argued. By the later Middle Ages, the Postillae had become, alongside the Glossa Ordinaria, one of the most widely copied and consulted biblical commentaries in Europe. The influence of Lyra’s approach only grew with time. His close attention to language, history, and textual coherence made his work especially attractive to early humanists, and later to reformers, who famously remarked that “if Lyra had not played, Luther would not have danced.” In print culture, this authority translated into remarkable scale. All or part of the Postillae appears in more than a dozen Latin Bibles printed before 1530, typically issued in imposing folio sets of four to six volumes. The first Latin Bible to incorporate Lyra’s commentary was printed in Venice in 1481 by Johannes Herbort for Johannes de Colonia and Nicolaus Jenson (no. 51). Although the manuscripts underlying this tradition were often illustrated, Herbort’s edition left blank spaces for later scribal decoration. The first Bible to include printed woodcut illustrations specifically designed to accompany Lyra’s commentary was produced by Anton Koberger in Nuremberg in 1485 (no. 63), further cementing Nicholas of Lyra’s place at the centre of late medieval and early modern biblical scholarship.

Paul Burgos (c. AD 1351-1435), also known as Paulus de Santa Maria, was a Jewish convert to Christianity who became bishop of Burgos in Spain. He was known for his Additiones to Nicholas of Lyra’s Postillae. In these he draw upon Jewish interpretations of the Bible to shed additional light on the Bible’s literal and historical meanings. This incorporation of Jewish perspectives contributed to a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the Biblical text and almost always appeared in printed bibles that included the Postillae. In the present instance, it can be found in nos. 51, 54, 63, 65, 74, 80, 84, 92, 96, 101, 106, 113.

Matthias Döring (Magister Matthias Doering) (fl. AD 1426-1469) was late medieval theologian who wrote the a series of refutations to Paul Burgos’s Additiones known as the Replicae. While Burgos’s Additiones appeared in all the bibles in this bibliography that included Lyra’s Postillae except one (no., 87), Döring’s Replicae can be found only in nos. 51, 54, 63, 65, 74, 80, 84, 92.

Finally, Guillelmus Brito, also known as William Brito, was a thirteenth or fourteenth-century lexicographer and theologian known for his Summa Vocabulorum Bibliae. It was sometimes also referred to as the Magna Glossatura or the Summa Britonis. Completed around 1300, the work is essentially a comprehensive glossary of the Latin Bible. The Summa is considered especially significant because it reflects the transition from glosses or commentaries that were connected directly to the text, to a more distinct form of lexical work that could be used as a reference independently of the text. It was a popular addition to Latin bibles printed before 1530 and can be found in nos. 51, 54, 63, 65, 74, 80, 84, 87, 89, 92, 96, 101.

❧ Further Reading

- Alexander Andree, “Glossed Bibles,” in H.A.G. Houghton (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Latin Bible (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023): 208-224

- Lesley Smith, The Glossa Ordinaria: The Making of a Medieval Commentary, Brill, 2009.

- David Salomon, An Introduction to the ‘Glossa Ordinaria’ as Medieval Hypertext, University of Wales Press, 2012.

- Deeana Copeland Kleeper, The Insight of Unbelievers: Nicholas of Lyra and Christian Reading of Jewish Text in the Later Middle Ages, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

- Philip D W Krey and Lesley Smith, editors, Nicholas of Lyra: The Senses of Scripture, Brill, 2000.

- Joy A. Schroeder, The Bible in Medieval Tradition: The Book of Genesis, Eerdmans, 2015.

❧ Some Historical Fiction

In the early 14th century, Nicholas, regent master of Theology, sits in his cell at the University of Paris, surrounded by the musty scent of old parchment and the faint waft of burning candles. The room is dimly lit, with sunlight filtering through narrow windows casting oblique rays of light onto the thick, wooden desk. The silence of the cell is palpable and almost sacred, as if the room is holding its breath, waiting for divine inspiration to flow through the pens of its occupants.

Lyra is a tall, gaunt figure, dressed in the plain brown robe of the Franciscan order, cinched at the waist with a simple rope belt. His tonsured head and hooded cowl frame a face marked by deep concentration and lined with the rigours of monastic life. A prominent nose and high cheekbones give him a sharp, eagle-like countenance, while his intense, brown eyes seem to bore into the pages before him. He leans over a desk, his posture slightly stooped, as if drawn magnetically to the texts spread before him. His right hand moves steadily, etching ink onto the parchment, while his left hand rests on an open tome, the words of which have inspired his current labour.

Nicholas’s desk is for him a kind of altar. And it is laden with books. One is a well-worn copy of the Bible in Latin, its pages full of annotations and bookmarks. Another is a Hebrew version of the Old Testament, ready evidence of Lyra’s commitment to learning the original languages of the sacred texts. Other volumes, some bearing the names of Thomas Aquinas, Raymond Martini, and even the works of the Jewish sage Rashi, are stacked on the desk or lie open, their texts crowded by dense annotations. Nicholas’ own quill moves across the page with a steady rhythm, occasionally pausing as he refers to one of the open books, his mind synthesising centuries of wisdom into his own unique commentary.

Nicholas is motivated by a deep sense of responsibility to the Scriptures. He is inspired by his studies and his exposure to Hebrew texts as he labours to clear the obfuscation that has pervaded biblical exegesis. He hopes that his “Postillae” will help, bringing a deeper and more grounded understanding to the clergy and, through them, to the people. He seeks especially to illuminate the literal sense of the Scriptures, stripping away the layers of allegory and speculation that, in his view, have complicated and abstracted their true meaning.

But doubts occasionally cloud his mind. Does he have the depth of understanding necessary to undertake this immense task? He is relying heavily on the works of Jewish scholars, and he wonders how this will be received by his fellow Christians. Will his work, grounded in Hebrew scholarship be accepted by the Church? He is acutely aware of the tension between tradition and innovation as he works to achieve that elusive and delicate balance between adhering to established doctrine while seeking fresh interpretations.

Lyra looks up from his writing, stretching his back and rolling his shoulders. His eyes linger on the flickering flames of the candles. He takes a deep breath as the smell of wax and parchment fill his nostrils. His duty, he reminds himself, is to the truth and therefore to a faithful and accurate understanding of the Scriptures. He dips his quill into the inkwell and continues to write.

Somebody essentially help to make seriously articles I would state. This is the very first time I frequented your web page and thus far? I amazed with the research you made to create this particular publish incredible. Fantastic job!

LikeLiked by 1 person