❧ Introduction

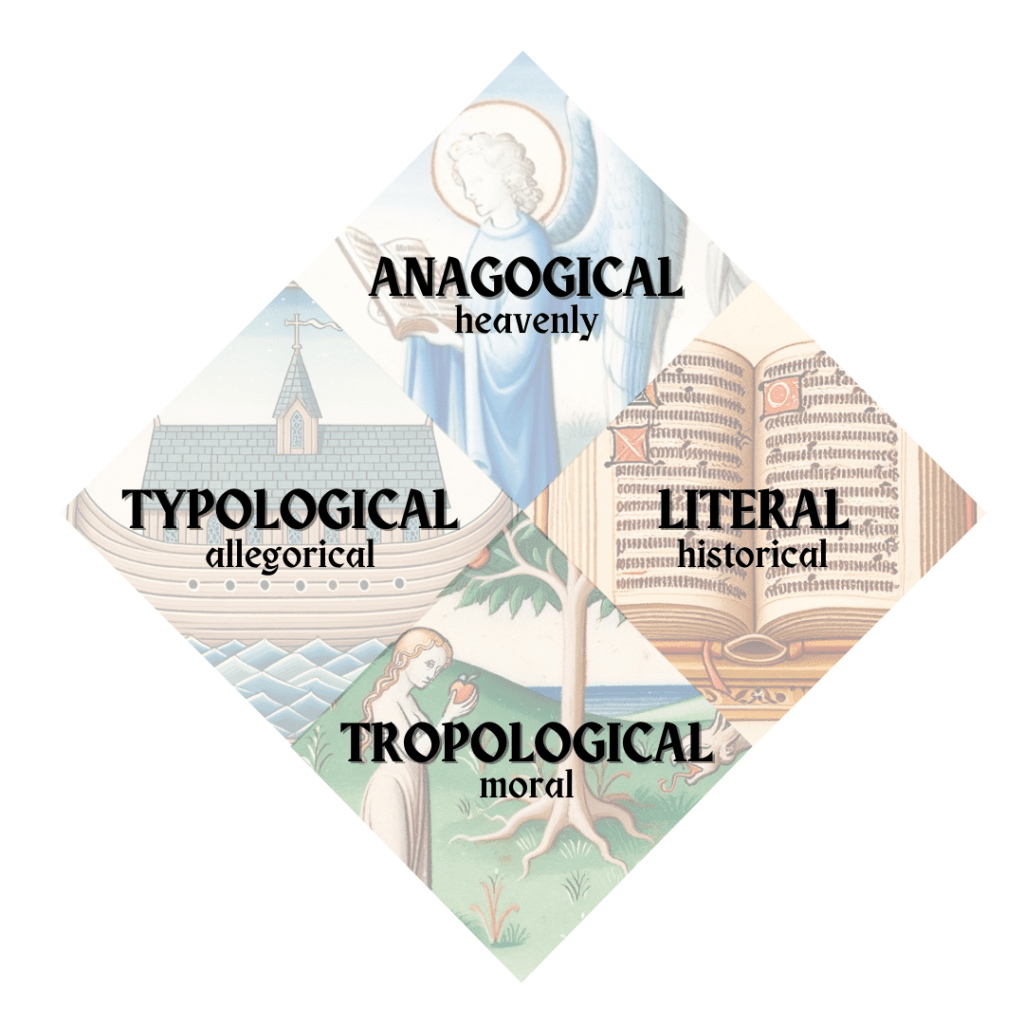

In 1487, Nicholas Kesler published a Latin Bible that included a brief introductory text explaining the four ‘senses’ or ways to understand Scripture: the literal or historical, the allegorical, the anagogical, and the tropological. Also known as the Quadriga, this interpretive framework originated in the early church and was developed throughout the Middle Ages. Briefly, the literal sense refers to the plain and direct meaning of the text, what the words themselves say, and the events and facts they describe. The allegorical sense involves symbolic or figurative interpretation, often revealing deeper theological truths or foreshadowing Christ. The moral sense applies the text to the life of the individual reader, serving as ethical guidance or instruction. Finally, the anagogical sense concerns eschatology, pointing towards heavenly realities and the ultimate destiny of humanity.

After making its first appearance in 1487, the Modi intellegendi became a standard preface in countless subsequent editions of the Latin Bible throughout the Renaissance and beyond. Interestingly, the Catechism of the Catholic Church acknowledges this interpretative approach and the four ‘senses’ of Scripture to this day.

❧ Modi intellegendi as it appears

in Sacon’s 1509 Biblia

❧ Corrected Latin Text

- Modi intellegendi sacram scripturam

- Notandum quod omnis sacra scriptura quadriformi ratione distinguitur sive exponitur.

- Aut enim in historico vel litterali intellectu, aut in allegorico, aut in anagogico, aut in tropologico vel morali solet accipi.

- Historia namque est quod res aliqua, quomodo quam litteram dicta vel facta sit, plano sermone refertur, ut cum dicitur.

- Populus Israel ex Egypto salvatus, tabernaculum Domino fecit. Et dicitur ab historia, id est, videre vel cognoscere, quod antiquitus nemo scribebat historiam nisi qui vidisset. Et sic quando dictiones intelliguntur simpliciter ut sonant, est sensus litteralis vel historicus.

- Allegoria autem est cum verbis aut rebus mysticis praesentia Christi et ecclesiae sacramenta signantur.

- Verbis videlicet ut ait Esaias. Egredietur virga de radice Iesse: quod aperte est dicere. Nascetur virgo Maria de stirpe David: et de ea Christus nascetur.

- Rebus mysticis, est populus Israel ab Aegyptiaca servitute per sanguinem agni liberatus.

- Allegorice ecclesiam signat quae per passionem Christi a daemoniaca servitute liberata est.

- Et nota quod allegoria multis modis exponitur. Quandoque a persona ut Isaac signat Christum. Quandoque a re et non persona: ut aries occisus significat Christi carnem passam.

- Quandoque a loco: ut Christus praedicaturus ascendit in montem: ubi eminentia loci signat eius sapientiam et excellentiam. Quandoque a numero ut apprehenderunt septem mulieres virum unum, id est, septem dona gratiarum Christi. Quandoque a negocio vel facto: ut interfectio Goliath a David, interfectionem diaboli in Christo signat.

- Anagogia autem ad superiora est ducens locutio: quae de premio futuro et ea quae in caelis est vita futura apertis sive mysticis sermonibus disputat. Apertis: ut cum dicitur. Beati mundo corde. Mysticis: ut cum dicitur Beati qui lavant stolas suas ut sit illis potestas in ligno vitae: et per portas intrent civitatem. Quod sic exponitur anagogice.

- Beati qui mundant cogitationes suas et actus ut sit illis potestas videndi dominum nostrum Iesum Christum: qui dicit: Ego sum via vitae et veritas. Per doctrinam et exempla precedentium patrum intrant in regnum caelorum.

- Et sic est differentia inter allegoriam et anagogiam: quod allegoria est mystericus sensus pertinens ad militantem ecclesiam in qua sumus: sed anagogic est apertus sensus pertinens ad ecclesiam triumphantem: quae est communitas sanctorum iam triumphans et regnans.

- Tropologia vero est moralis locutio quae ad instructionem et correctionem animorum mystice sive aperte respicit.

- Mystice ut ait Salomon. Omni tempore sint vestimenta tua candida: et oleum de capite tuo non deficiat. Quod est dicere. Omni tempore sint opera tua munda: et charitas de corde tuo non deficiat.

- Aperte: ut Johannes dicit. Filioli, non diligamus verbo neque lingua: sed opere et veritate. Et ut breviter habeas, historia docet factum. Tropologia faciendum. Allegoria credendum. Anagogia appetendum. Unde versus.

Littera gesta docet quid credas allegoria,

Moralis quid agas: quo tendas anagogia.

- Haec patent in hac dictione Hierusalem. Historice enim est nomen civitatis. Tropologice est typus animae fidelis. Allegorice figura Ecclesiae militantis. Anagogice typum gerit Ecclesiae triumphantis. Unde versus:

Sicut Hierusalem polis est terna fidelis,

constat Ecclesia mons fortis patria summa.

❧ English Translation

- How to Understand Sacred Scripture.

- It is important to understand that the entire Sacred Scripture can be interpreted or explained in four distinct ways.

- It is usually interpreted in a (1) historical or literal sense; or (2) allegorically; or (3) anagogically; or in a (4) tropological or moral sense.

- Now then, a historical account relates how something was said or done according to the letter, in plain speech, just as it is said.

- The people of Israel, having been saved from Egypt, built a tabernacle for the Lord [Ex 25-40]. History is about seeing and knowing, and no one in ancient times would write history unless he had witnessed the events himself. And so, when words are interpreted simply as they are written, that is considered the literal or historical interpretation.

- An allegory, however, is when the presence of Christ and the sacraments of the Church are signified through a mystical reading of words or objects.

- For example, when Isaiah writes: “A branch will grow from the root of Jesse” [Is 11:1], it clearly means that the Virgin Mary will be born from David’s lineage, and from her, Christ will be born.

- From a mystical point of view, the story of the Exodus refers to the people of Israel being liberated from Egyptian bondage through the blood of the Lamb [Ex 12:7, 13].

- In an allegorical sense, it signifies the church being liberated from demonic servitude through Christ’s passion.

- Note that allegories can be interpreted in various ways. Sometimes they are represented by a person, as Isaac represents Christ. Other times, they are represented by a thing rather than a person: such as the slain ram signifying the suffering body of Christ [Gn 22:1-18].

- At times, the symbolism comes from a place: as when Christ ascended the mountain to preach, where the mountain’s height signifies His wisdom and excellence [Mt 5:1-2]. At other times, it’s drawn from a number: as when seven women clung to one man, representing the seven gifts of Christ’s grace [Is. 4:1]. It can also be derived from an action or event: as David’s slaying of Goliath represents Christ’s defeat of the Devil [1 Sam 17].

- Anagoge, however, is a discourse that guides us towards higher things: it discusses the future reward and the afterlife in Heaven, using either explicit or mystical language. An example of explicit language is ‘Blessed are the pure in heart’ [Mt 5:8]. An example of mystical language is ‘Blessed are those who wash their robes, so that they may have the right to the tree of life and may enter the city by the gates’ [Apoc 22:14]. These are interpreted in an anagogical manner.

- Blessed are they who purify their thoughts and deeds, for they will be granted the ability to see our Lord Jesus Christ, who proclaimed: ‘I am the way, the truth, and the life’ [Jn 14:6]. Through the teachings and examples of our forefathers, they gain entrance into the Kingdom of Heaven.

- And herein lies the difference between allegory and anagoge: allegory refers to a mystical interpretation related to the church militant here on Earth, whereas anagoge refers to the revealed understanding associated with the triumphant church, which is the community of saints, already triumphant and reigning.

- Tropology, on the other hand, is a type of discourse that is moral in nature, aimed at the instruction and correction of souls, whether in a mystical or explicit manner.

- Mystically, Solomon says, ‘Let your garments always be white, and let not oil be lacking on your head’ [Ecc 9:8]. Or, in other words, ‘Let your actions always be pure, and may charity never be lacking in your heart.’

- As John says clearly, ‘Dear children, let us not love with words or speech but with actions and in truth’ [1 Jn 3:18]. In a word, then, history teaches what has been done. Tropology instructs us on what should be done. Allegory what to believe. And anagoge what to aspire for. From this, the verse follows:

The letter reveals the deeds, allegory what to heed,

Morality steers actions, to Heav’nly satisfaction.

- These interpretations are apparent in the word ‘Jerusalem’. In the historical sense, it is the name of a city. In a tropological sense, it symbolises the faithful soul. Allegorically, it represents the Church at war. Anagogically, it embodies the triumphant Church. From this, the verse follows:

Just as Jerusalem, God’s city thrice shown,

The Church a firm mountain, forever our home.

❧ Further Reading

- Ian Christopher Levy, Introducing Medieval Biblical Interpretation: The Senses of Scripture in Premodern Exegesis, Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2018.

- Henri de Lubac, 1959-1964, Medieval Exegesis: The Four Senses of Scripture, 3 vols., translated by Mark Sebanc (vol. 1) and E. M. Macierowski (vols. 2-3), Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998-2009.

❧ Some Historical Fiction

Late summer 1517, and the atmosphere in Wittenberg was full with the distant scent of rain. A light mist crept across the surroundings, making the buildings seem strangely insubstantial. Somewhere, a street musician played a soft lute, its melancholy notes wafting through the evening air.

Erasmus, tall and imposing with sharp features, stood with his signature circular glasses perched on his nose, his clean-shaven face a stark contrast to the bearded scholars of the age. He wore an intricate robe, marking him as an intellectual of distinction. Beside him was Martin Luther, stocky with an intensity in his eyes that seemed to pierce through the fog. His simple Augustinian habit and tonsured head belied the firm set of his jaw, suggesting a man driven, even reckless, in his determination.

The inn was smoky and only dimly lit by a handful of tallow candles whose flames guttered and danced silently. Drawn up together to a small table, the two men huddled over a single volume of Nicholas Jenson’s Biblia Latina cum postillis Nicolai de Lyra — an unwieldy folio scored by forty years’ worth of cramped annotations. De Lyra, a Franciscan friar born in Normandy in the thirteenth century who spent much of his life at the University of Paris, was a great favourite of the outspoken Augustinian. Despite the fact that de Lyra’s biblical commentaries were by this time almost two hundred years old, they somehow spoke to Luther with an immediacy that even he could hardly believe.

Luther’s voice, hoarse yet passionate, broke the silence, “Erasmus, this Quadriga, it’s an entanglement, a convolution! God’s Word, as I’ve come to understand from de Lyra, should be approached in its historical and literal sense. To shroud it in layers of allegory, morality, eschatology, is to move away from its intended meaning. And this Modi intellegendi that seems to preface almost every new edition of the Bible will only confuse readers further.”

Erasmus, always contemplative, paused to choose his words. “Intended meaning? Are you to be the judge of that, my friend? Martin, come now, while I respect de Lyra’s approach, the Quadriga offers rich veins of potential understanding. The world of Scripture is vast, and not every intention, not every truth, can be seized upon through blunt literalism alone. Readers need guidance.”

Luther’s fingers drummed impatiently on the wooden surface, “The Holy Scriptures should speak directly, Erasmus. The Holy Spirit is the only guide a reader needs. When Christ speaks of Jerusalem, I wish to see its streets, its people. Not be lost in a labyrinth of dizzying interpretations.”

Leaning forward, Erasmus countered, “Yet, to limit ourselves to just the literal is to miss the divine mysteries God wishes to unveil. Remember, not everything — not you, not this tavern, not this town — can be fully grasped from just one perspective. The Quadriga is more than just a path or a guide. No, it is a set of paths, all driving toward the same end. And that end, Martin, is Truth. What you propose would, I fear, result in anarchy.”

“Bah,” Luther responded, becoming exasperated, “All this subtlety only risks making the Scriptures distant, unknowable. I’ve felt the Bible’s power. I’ve known its immediacy. Reading it should be like having a living conversation with the soul, unmediated by arcane frameworks.”

The two men, their faces twisted by the flickering of the candlelight, seemed to embody the fissure that would soon engulf Christendom. Outside, a sudden gust of wind carried the scent of impending rain. And as the evening shadows deepened, the world around them stood still. For a moment. For just one more moment.