❧ Introduction

When Johannes Gutenberg finished printing his magnificent Biblia Latina around 1454 or 1455, he created not only the first substantial printed book in the Western world, but also inaugurated an irrevocable transformation in the way Scripture would henceforth be encountered, preserved, and shared. In that act, the Word of God, which had long been entrusted to the slow and careful labour of scribes, was set to evolve in the succeeding decades into something possessing a deeper and more immediate cultural reach.

Yet the Gutenberg Bible, splendid though it remains, was not an inexpensive book. It would take many years before smaller and less costly bibles eventually appeared. Although relatively widespread access (and still highly constrained by modern standards) would remain little more than a promise until the 1480s or even 1490s, it is worth considering in detail the four Latin bibles that emerged from the presses of different printers and cities before the year 1465. Each was a milestone in its own right. Following Gutenberg’s own Bible, we have the Latin Bible of Johann Mentelin in Strasbourg (c. 1460), the enigmatic 36-line Bible produced in Bamberg (not after 1461), and the 1462 edition of Johann Fust and Peter Schöffer in Mainz, distinguished as the first Bible to bear a printer’s imprint.

Together, these four editions form a tetralogy of invention and enterprise, each standing at a slightly different angle to the revolutionary force Gutenberg had unleashed. They mark not only the first steps of print culture but the first quiet cracks in an old world, as the sacred text—once the guarded possession of Church and monastery—began to slip into a wider, more restless world. Examining them side by side reveals not merely a technical triumph, but the ambition, the rivalry, and the restless energy with which the Word was set loose upon the world in movable type—and with it, the first distant rumblings of a more modern age.

❧ B42 – The Gutenberg 42-line Bible

In the history of the book, almost nothing can rival the Gutenberg Bible. To call it the first printed Bible is accurate; to call it the first printed book of consequence is scarcely less so. Yet the achievement was not simply technical. In bringing the sacred text of Scripture into a new material form — the reproducible, standardised, mass-producible codex — Gutenberg and his collaborators reshaped both the physical and the spiritual landscapes of Europe.

Johannes Gutenberg himself remains an elusive figure, half-shrouded in the mists of legend. Born around 1400 into the patrician class of Mainz, he was trained as a goldsmith and metalworker, a background that proved indispensable when he began experimenting with moveable type. By the 1440s, Gutenberg had devised a system that combined durable metal type, an oil-based ink suited to the absorption rates of paper and vellum, and a press adapted from wine-making or cloth-printing models. Yet the scope of his ambition required more than mechanical ingenuity: it demanded capital. Thus entered Johann Fust, a wealthy financier who loaned Gutenberg a substantial sum to fund the venture. Alongside them worked Peter Schoeffer, a gifted scribe who would eventually become Fust’s son-in-law — and, fatefully, his business partner.

Everything we know about what followed comes from legal records. In 1455, Fust sued Gutenberg, alleging mismanagement of funds. The court sided with Fust, who seized Gutenberg’s printing workshop, materials, and employees. Thus it was that Fust and Schoeffer, not Gutenberg himself, would continue to build the first recognisable printing house of the West. But by then, the Gutenberg Bible had already been created: a project so ambitious, so vast in scope, that it was almost impossible to rival.

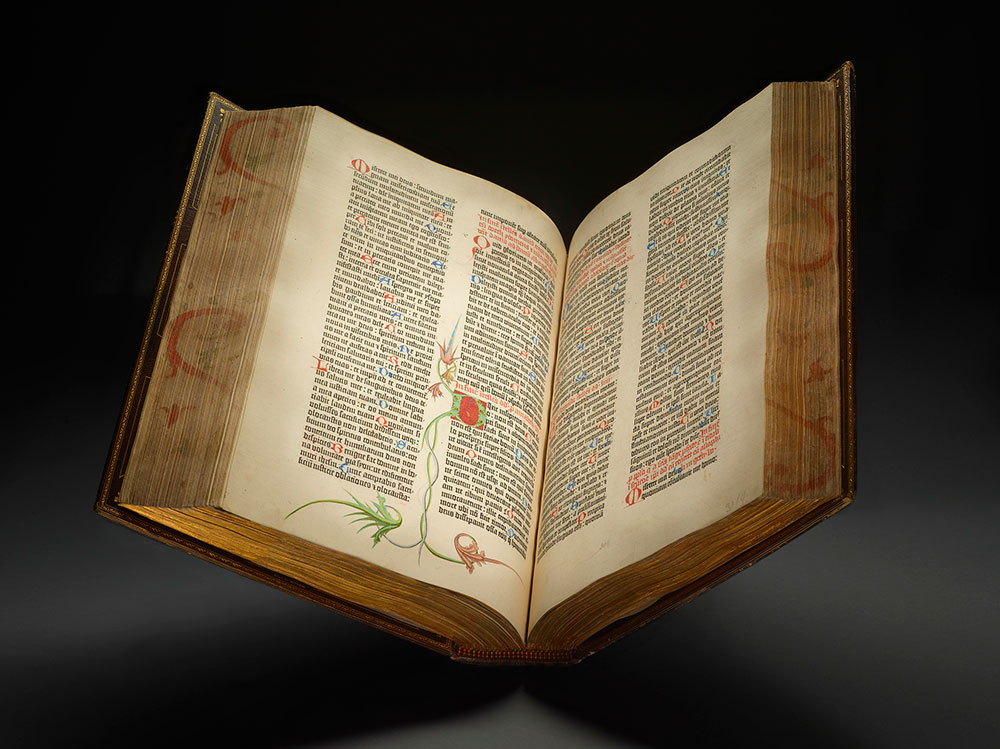

The Gutenberg Bible, or the B42 as it is often known (referring to its 42-line columns of text), comprises the full Latin Vulgate text, laid out in a format designed to echo the grandest manuscript bibles of a much earlier time. Though its text was derived from the small and portable thirteenth-century Paris Bible tradition, the Gutenberg Bible was meant to hearken back to the large and imposing lectern bibles of the tenth and eleventh centuries. In this way, though revolutionary from a technological standpoint, the Gutenberg Bible would probably have struck the eye of a fifteenth century reader as rather an old-fashioned book in its material form. At the same time, Gutenberg’s distinctive typeface was modelled closely on the textura script beloved of high medieval scribes writing in the thirteenth century and later. Gutenberg also deliberately left blank spaces to allow for hand-illuminated initials, marginalia, and rubrication. The result was that each copy could still be made unique, allowing patrons to retain the sense of the idiosyncrasies of the manuscripts with which they were so familiar.

Estimates suggest that around 160 to 180 copies of the Gutenberg Bible were originally printed in Mainz, most on paper and perhaps 30 to 45 on luxurious vellum. Today, just 49 copies survive in any form—of these, approximately 21 or 22 are relatively complete; the rest are fragmentary. The Library of Congress in Washington, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris, the British Library in London, and the Huntington Library in California all possess reasonably complete copies printed on vellum. Among these, the Huntington copy is especially noteworthy—still in its original binding and richly illuminated. Among the paper copies that survive, the Morgan Library & Museum in New York holds three—the largest single holding in the world—although at one is incomplete. Other major institutions with complete or near-complete copies include Harvard, Yale, Princeton’s Scheide Library, the Harry Ransom Center in Texas, the New York Public Library, the Vatican Library, and several national libraries across Europe.

The choice of the Bible as the first major printed work was no accident. Scripture was the beating heart of medieval Christian life: the source of doctrine, devotion, and authority. It also commanded a huge potential market. But by setting the Bible in type, Gutenberg was doing more than exploiting a potential market or demonstrating the capacity of his invention: he was also offering the world the Word of God, made newly accessible, newly stable, newly proliferable. Though little is known about Gutenberg’s personal faith, it was undoubtedly an act of profound religious daring.

The impact was immediate, though the first ripples were largely confined to ecclesiastical and scholarly elites. A printed Bible was, after all, still a costly item, though markedly less so than a manuscript equivalent. More importantly, it was standardised. Errors crept into hand-copied manuscripts over time, and variants proliferated. The Gutenberg Bible, by contrast, offered a singular, unified text, multiplied with extraordinary fidelity across its entire run. In this respect, it anticipated one of the most important and sometimes troubling aspects of the printing revolution: the paradox that printing preserved texts perfectly, even as it froze their imperfections more indelibly than any scribe could have done.

In choosing the Latin Vulgate, Gutenberg demonstrated an acute understanding of his cultural moment. Latin remained the language of the Church, the universities, and the law. Vernacular translations would come in time — and with them, fierce theological battles — but for now, the Vulgate was an uncontroversial choice, at once a spiritual offering and a practical investment. Indeed, the very fact that Johann Mentelin would produce a printed Latin Bible at Strasbourg by about 1460 shows how swiftly Gutenberg’s idea inspired others. Mentelin’s work, while less technically dazzling, underscores how the printed Bible was not a singular miracle but the beginning of a flood.

It is difficult to overstate the technological sophistication embodied in the Gutenberg Bible. Each letter was cast individually in a hand-mould; each page had to be composed, inked, pressed, and dried before the next could begin. Alignment, ink distribution, and type wear all posed constant threats to uniformity. Gutenberg’s workshop operated on a scale and with a precision that no scriptorium could have matched. And yet — marvellously — the Gutenberg Bible does not feel like a mechanical object. It breathes. It has presence. Its careful layout, its luminous margins, its invitation to illumination — all conspire to make it feel more, not less, like a holy book.

The ironies of Gutenberg’s fate are poignant. Having lost his press to Fust, Gutenberg himself fell into relative obscurity. He was later granted a modest pension by the Archbishop of Mainz, and he died in 1468, never having reaped the full rewards of his genius. Meanwhile, Fust and Schoeffer carried the craft forward, refining techniques, signing their names, and producing the celebrated 1462 Latin Bible that would bear, for the first time, the proud imprint of its makers. That Gutenberg’s name is remembered where Fust’s and Schoeffer’s are often footnotes is, perhaps, a final act of providence. It was Gutenberg, after all, who first fused faith and technology into the form that would carry the Word — and all words — into the modern age.

The Gutenberg Bible is more than a technological marvel. It is also a theological argument about the transformation of an ancient and immutable Scripture through an utterly new medium. Like the river Arnon in the days of Moses, it marks a boundary: dividing two eras, but also connecting them, as a sacred bridge from the age of the scribe to the age of the press.

❧ B49 – Mentelin’s Latin Bible

If the Gutenberg Bible stood as the majestic fountainhead of the printed book, it was not long before its waters spread outward, touching other hands and other cities. Among the first to seize upon Gutenberg’s momentous idea was Johann Mentelin of Strasbourg, who by 1460 had produced the second printed Latin Bible — a work that, though less sumptuous than Gutenberg’s, was no less significant for the future of Scripture in print.

Johann Mentelin remains, like Gutenberg himself, a figure glimpsed through only the scantest historical records. Born around 1410 in Schlettstadt, now Sélestat in Alsace, Mentelin was trained as a scribe and illuminator, the old arts of the manuscript world into which he had been apprenticed since youth. Strasbourg, where he eventually established himself, was a city poised for the new: a flourishing centre of commerce, scholarship, and ecclesiastical power, lying just beyond the immediate shadow of Mainz yet close enough to catch the first trembling echoes of Gutenberg’s invention. It is tempting to imagine — though it cannot be proved — that Mentelin or his associates had some direct knowledge of the Mainz experiments. Printing secrets travelled quickly and uneasily in those early years; friendships, rivalries, and betrayals were as common as in any new industry, and Strasbourg’s openness to new ideas made it fertile ground for a press.

By about 1458, Mentelin had somehow established a printing workshop of his own, one of the very first beyond the circle of Gutenberg’s direct collaborators. His great enterprise, completed around 1460, was a full Latin Bible: the Biblia Latina sometimes known today as the B49 for its 49 lines of text per column. This edition stands distinct from Gutenberg’s work in several key ways. Where Gutenberg had aimed at magnificence, echoing the great lectern bibles of the medieval scriptorium, Mentelin’s Bible was slightly more compact, slightly more workmanlike — though still a royal folio meant to be read by priests, scholars, and monastic communities rather than by the solitary layman.

The Mentelin Bible was printed in a clear Gothic typeface, notably rounder and more open than Gutenberg’s dense textura. Like Gutenberg, Mentelin left spaces for hand-painted initials and rubrications, allowing each copy to be individually adorned, thus softening the mechanical regularity of type with the personal artistry of the scribe. But unlike Gutenberg, he included no colophon whatsoever. It was the sacred text itself, not the human craftsman, that was meant to stand foremost. In this way, Mentelin remained closer to the traditions of the manuscript age even as he helped usher in the printed one.

The choice to print another Latin Bible, despite the formidable precedent set by Gutenberg, reflects something important about the moment. Demand for Scripture in Latin was not exhausted by a single edition, however splendid. Throughout Europe, monasteries, universities, and cathedral chapters needed bibles that were faithful and increasingly affordable. Mentelin’s Bible, slightly less costly to produce, answered that need. It is telling that while fewer copies of the Mentelin Bible survive today — some twenty-five in institutional libraries — they all show signs of heavy use, evidence that these were working books, read and studied rather than stored away as treasures.

Mentelin’s background as a scribe left its mark on his text in other ways as well. His edition follows the traditional Vulgate order and text but shows a practical mind at work: the layout is efficient, the margins generous enough for notes and glosses. There is an unpretentiousness about the work, a sense that this Bible was meant to be lived with, not merely admired from a distance.

It is possible — though once again the evidence is tantalisingly thin — that Mentelin’s press served as an inspiration for another great printer of Strasbourg, Heinrich Eggestein, whose later editions would continue the spread of the printed Bible. What is clear is that by 1460, Strasbourg had become, alongside Mainz and Bamberg, one of the first true printing centres of Europe. Mentelin’s Bible stands at the threshold of this new world: a bridge between Gutenberg’s singular burst of genius and the broader flowering of the printed word across Christendom.

That Johann Mentelin would go on, a few years later, to print the first vernacular Bible in German speaks volumes about the instincts that animated his press. Yet it is his Latin Bible of 1460 that rightly claims his first laurels. In it we see printing beginning to shed its experimental cloak and to don the garments of daily use. Here was no grand showpiece, no isolated marvel: here was the Bible, printed, multiplied, and sent into the world — not to dazzle, but to teach, to nourish, to save.

If Gutenberg’s Bible was a cathedral in print, the Mentelin Bible might be likened to a great parish church: solid, capacious, less ornate perhaps, but built for the daily tread of faithful feet. Today, approximately 25 copies are known to survive (making it rarer than the Gutenberg Bible), most of them in institutional libraries across Europe and North America. Notable examples include the copy at Freiburg, whose volumes are rubricated and dated 1460 and 1461 respectively, and the finely rubricated Princeton Scheide Library copy, which has been digitised in full.

❧ 36-Line Bible

Though much has been learned by bibliographers and book historians in recent decades, the 36-line Bible remains something of an enigma—a bridge between the known and the speculative in the nascent world of print. For many years, scholars believed this edition predated Mentelin’s Latin Bible, and perhaps even the Gutenberg Bible itself, largely on account of its earlier and more primitive type. Yet meticulous textual analysis has since revealed that, with the exception of its initial pages, the 36-line Bible was set directly from a copy of the Gutenberg Bible, thereby situating it chronologically after Gutenberg’s masterpiece. The correspondence between the texts is striking: typesetting errors found in Gutenberg’s edition are sometimes faithfully reproduced in the 36-line Bible, while other errors are corrected or altered, suggesting not merely influence but direct dependence upon a specific exemplar.

The 36-line Bible takes its name from the number of lines per column, a format that yields a more voluminous work than either the Gutenberg or Mentelin editions. Comprising 884 leaves, it was typically bound in two or even three volumes, forming a substantial set of tomes intended for ecclesiastical or scholarly use rather than private devotion. Compared to the spacious and carefully designed layout of the Gutenberg Bible, the 36-line Bible has narrower margins and tighter spacing, with an eye, perhaps, to saving paper costs without sacrificing the integrity of the text.

The typeface employed is known as the Donatus-Kalendar (D-K) type—a cruder and older design than the magnificent textura of Gutenberg or even the neater gothic types used by Mentelin. The D-K type had previously served for the printing of small-format works such as Latin grammars and calendars, where elegance was less important than legibility and speed of production. Its use in the 36-line Bible suggests a printer who either had limited access to more refined typefaces or who deliberately chose a more workmanlike style for economic or practical reasons. In either case, it hints at a different conception of what a printed Bible might be: less a lavish monument and more a reliable, accessible text.

Questions surrounding the 36-line Bible’s origins have long intrigued historians. The absence of a colophon or printer’s name complicates attribution, yet several lines of evidence point to Bamberg as its place of production. The paper used matches that found in other Bamberg printings, and early bindings show signs of local manufacture. Moreover, Bamberg’s quieter, less competitive environment may have offered a printer the opportunity to produce such a work away from the intense scrutiny and rivalry of Mainz and Strasbourg.

The identity of the printer remains a matter of debate. Albrecht Pfister, a cleric and printer active in Bamberg during the 1460s, has often been suggested, given his later use of the D-K type. However, the superior craftsmanship evident in the 36-line Bible—both in its typesetting and its general production quality—has cast doubt on his candidacy. It is plausible that the printer was someone who had acquired some of Gutenberg’s equipment, or had been trained in his workshop, carrying with him both the technical knowledge and the ambitions of his master. Some have even ventured the possibility that Gutenberg himself was involved, perhaps in exile from Mainz after the collapse of his original business; but in the absence of definitive evidence, such theories remain tantalising rather than conclusive.

The 36-line Bible thus occupies a curious place in the history of early printing. It is both derivative and independent, transitional yet rooted in the ambitions of the first great experiments with movable type. Only fourteen substantially complete copies are known to survive today, all on paper. No intact vellum copies exist, though fragments of vellum leaves have been found reused as binding waste, suggesting that some vellum copies were produced. Major institutional holders include the British Library, the Museum Plantin-Moretus in Antwerp, and a number of German libraries such as those in Bamberg, Berlin, Dresden, Leipzig, Göttingen, and Munich. In North America, Princeton’s Scheide Library holds a notable fragment, while the remaining copies are almost entirely clustered in European collections. Rubrication in some volumes dated as late as 1461 offers a reasonable terminus ante quem for the printing.

❧ The Fust and Schöffer Latin Bible

The Latin Bible printed by Johann Fust and Peter Schöffer in 1462 opened a bold new chapter in both book and Bible production. As mentioned earlier, the story of Fust and Schöffer is intimately tied to Gutenberg’s own triumph and ruin. After wresting control of Gutenberg’s invention away from him, Fust and Schöffer together built the first true commercial printing firm of the West, combining technical innovation with a shrewd understanding of business. It is no exaggeration to say that, while Gutenberg invented the printing press, Fust and Schöffer invented the printing industry.

Their 1462 Latin Bible, completed in the middle of August, embodies this new spirit. Set again in Mainz — the cradle of printing — the Bible was produced in the midst of political chaos. The so-called Mainzer Fehde (the Mainz feud) had torn the city apart in a bitter conflict for the archiepiscopal seat, leading to violence, pillage, and widespread upheaval. Yet in the midst of this storm, Fust and Schöffer accomplished a triumph of order, elegance, and beauty: a Bible that, while grounded in the Vulgate tradition, displayed a new maturity in typographic design.

The 1462 Bible is a royal folio, like its Gutenbergian predecessor, but it moves with a surer, more graceful hand. Schöffer’s contribution to the enterprise was profound: a former scribe, he designed an entirely new typeface for this Bible that was distinctly different from Gutenberg’s dense textura. Schöffer’s type was finer, more regular, and more readable—an elegant Gothic, balancing the dignity of the manuscript tradition with the clarity that printing demanded. It is a type that breathes, allowing the sacred text to flow without the visual heaviness that had marked earlier efforts.

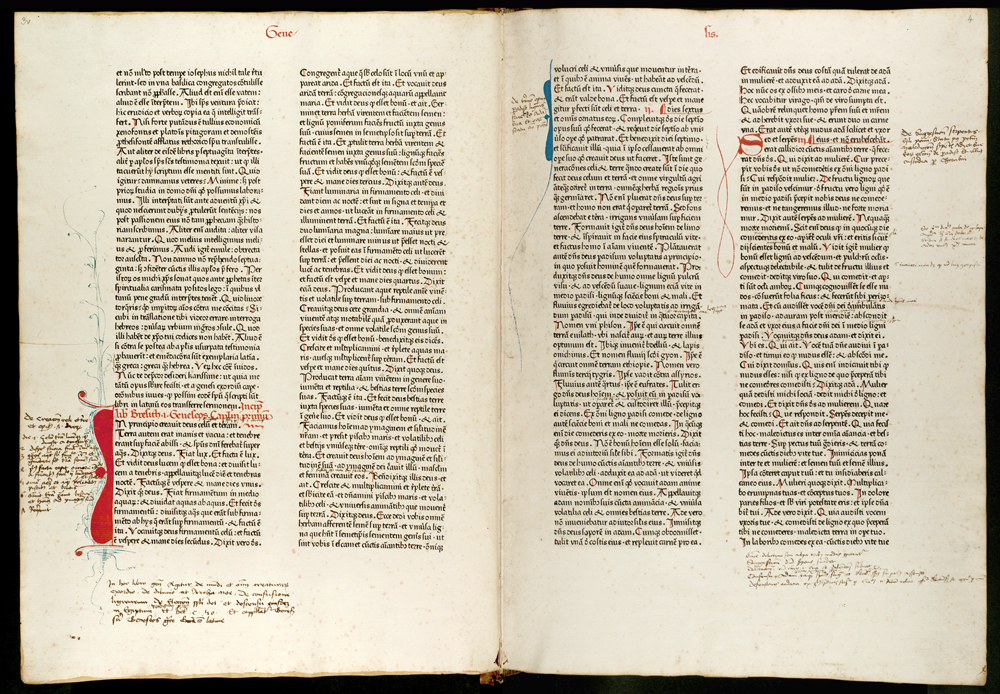

At least as daring as the new typography was the inclusion of a colophon at the end of the Bible, proudly proclaiming the names of its printers and the exact date of its completion. The colophon reads:

Presens hoc opusculum egregium absque ulla calami,

aut penne imitatione sic effigiatum et adinventum est

per Johannem Fust, civem maguntinum,

et Petrum Schöffer de Gernsheim,

anno Domini MCCCCLXII

in vigilia Assumptionis gloriosae Virginis Mariae.

This declaration was unprecedented. For the first time, the humble craftsmen of the book did not vanish behind their labour; they stood forth, naming themselves as creators—or at least as midwives—of the sacred Word. In doing so, they signalled that printing had moved beyond its tentative beginnings into a new, self-assured art.

The Fust and Schöffer Bible was no mere repetition of Gutenberg’s earlier effort. Because it was slightly taller than the Gutenberg Bible, owing to the increase to 48 lines per column (compared to 42), fewer leaves were needed overall: about 239 per volume, rather than the 324 and 319 leaves required for Gutenberg’s two volumes. The result was a book that was more economical without sacrificing much in the way of grandeur. The text was also laid out with a new rationality, allowing for better use of the page. As with previous bibles, spaces were left for illuminated initials and rubrication, enabling each copy to be painted and decorated according to the patron’s taste and purse.

This Bible has by far the highest survival rate of those under consideration—a testament to its wide circulation and the robust quality of its production. It was clearly meant to serve both institutions and wealthy individuals, reflecting an early awareness of the broader market for printed Scripture. Perhaps ironically, the same political chaos that saw Mainz plunged into conflict also hastened the spread of printing beyond its walls, as displaced craftsmen carried their knowledge into other cities across Europe.

The 1462 Bible thus stands at a crossroads. It looks backward to the manuscript tradition and to Gutenberg’s own heroic struggle. But it also looks forward—toward a Europe in which printers would sign their works, cultivate their reputations, and treat the production of sacred books as both a calling and a business. In a sense, Fust and Schöffer finished Gutenberg twice over: first by taking from him the physical fruits of his invention, and then by refining and successfully commercialising the art he had so laboriously brought into being.

Yet for all that, the 1462 Bible is no cynical production. Its leaves shine with a profound respect for the text they carry. Its type dances with restrained joy. Its colophon, far from being a mark of arrogance, stands instead as a witness to human collaboration—a blend of piety and ingenuity—that made such a miracle possible. One might even say that the Fust and Schöffer Bible brought the first decade of printed Latin bibles to a kind of natural fulfilment. The 1462 Bible survives in remarkable numbers: almost eighty substantially intact copies can be found in institutional libraries across Europe, North America, and beyond, among which are some twenty vellum copies. Particularly notable copies include the richly illuminated vellum example once in the Duke of Cassano‑Serra’s library in Naples (and auctioned in 2019 for just over €1,000,000), as well as the finely decorated versions in the Morgan Library, the British Library, and the Bridwell Library at Southern Methodist University. This high survival rate reflects this both the 1462 Bible’s initial success in the market and the extraordinary craftsmanship that went into its production–craftsmanship that made it worth preserving with great care down though the centuries.

❧ Concluding Thoughts

The first generation of printed Latin bibles—Gutenberg’s towering original, Mentelin’s steady replication, the shadowy craftsmanship of the 36-line Bible, and Fust and Schöffer’s polished triumph—together form a tetralogy of beginnings. Each bears witness to a different facet of the same great upheaval: the translation of the Word from manuscript to type, from the labour of the scriptorium to the marvellous multiplication of printed books. Yet there is another wonder hidden in their very existence: none of these bibles was printed under the direct auspices of the Church. They were sacred texts, but not ecclesiastical productions. No bishop commissioned them; no papal court oversaw them; no cathedral chapter dictated their design. They were ventures of private men—bold in spirit, devout in purpose, entrepreneurial in means—who seized the means of replication and set the Scriptures loose into the world without asking permission. It is a striking thought. In this beginning, the Bible belonged not to bishop or pope, but to printer and workshop. And in that quiet revolution—cloaked at first in the solemn black of moveable type—there already stirred the great and turbulent freedoms that printing would one day awaken.