In the final decade of the fifteenth century, two different printers in two very different settings produced nearly identical artefacts: small-format Latin bibles, printed in octavo, without glosses, and structured for ease of navigation. Johann Froben in Basel and Hieronymus de Paganinus in Venice each issued two octavo Latin bibles—Froben in 1491 and 1495, Paganinis in 1492 and 1497—that together form a distinctive bibliographic cluster. While similar in form and function, these bibles emerged from markedly different cultural and intellectual climates, and their convergence reveals a fascinating story of parallel innovation, shaped by geography, religious culture, and shifting patterns of readership.

❧ Historical and Geographical Contexts

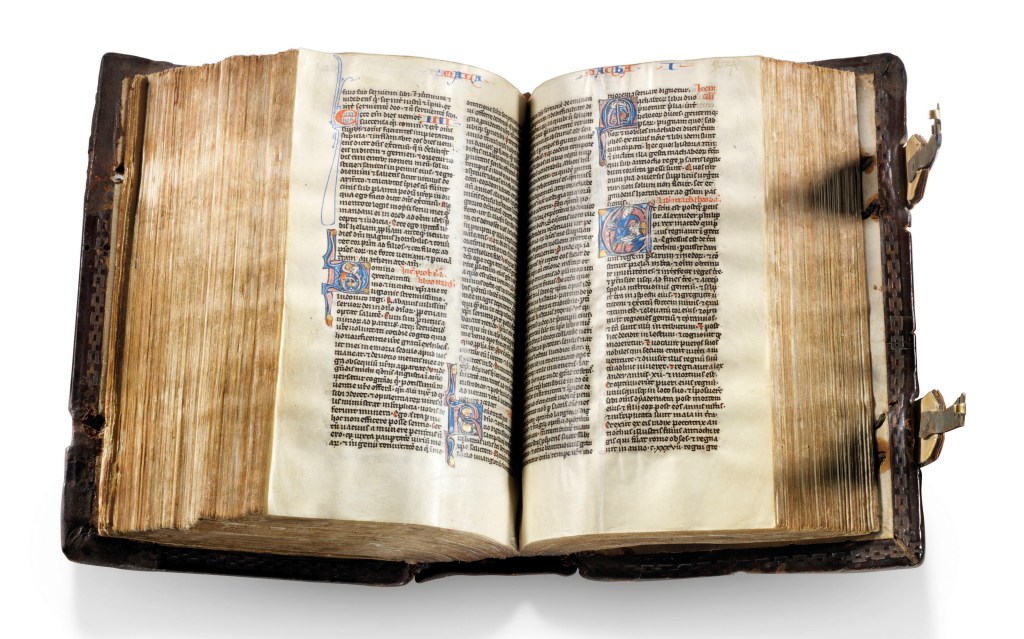

Though printed independently, all four editions harken back to the Paris bibles of the thirteenth century: compact, complete, unglossed, and structured for practical use. These manuscript bibles had once been indispensable tools for friars, university students, and preachers. But the comparatively laborious production of Paris bibles dropped off sharply after the thirteenth century, having saturated their intended market. By the late fifteenth century, many of these manuscripts had aged out of use, and a new generation of readers—clergy, scholars, and educated laypeople—faced a scarcity of affordable, complete Latin bibles.

Europe in the 1490s was on the cusp of epochal change. In the north, humanism was taking root in university towns like Erfurt, Paris, Louvain, and Basel, bringing a fresh interest in philology, textual criticism, and the moral reform of Church life. The devotio moderna movement, born in the Low Countries, stressed interiority, meditation on Scripture, and the imitation of Christ—fostering a class of devout readers who needed portable bibles for study and contemplation. In Italy and the southern regions, the Renaissance was more visual, civic, and artistic, but still rooted in the textual revival of antiquity. The Venetian Republic, meanwhile, stood at the pinnacle of European printing: a city of polyglot traders, ambitious printers, and competing religious orders. These diverging cultures of reading met in the press.

❧ Johann Froben

Johann Froben, situated in Basel, responded to this need from within a distinctively northern European context. Basel was a university town and a centre of humanist scholarship. Froben had apprenticed with Anton Koberger in Nuremberg and later partnered with Johann Amerbach, gaining experience in large-format theological works. Yet by the early 1490s, Froben turned from the monumental folio to something smaller, more mobile, and more personal. His 1491 octavo, often called the “Poor Man’s Bible,” was not designed for pulpit use but for the hand. It included navigational tools—chapter divisions, a subject index, and tabular summaries—but no interpretive glosses. Its austerity and accessibility made it suitable for the growing class of readers shaped by the devotio moderna and northern European humanism.

Froben was more than a printer; he was an early publisher in the modern sense—curating texts, working closely with authors and editors, and building a network of scholarly collaborators. In later decades, he would become Erasmus’s principal printer, producing the groundbreaking Novum Instrumentum in 1516 (after 1519, known as the Novum Testamentum Omne). But even in the 1490s, Froben was already positioning himself as a printer for serious readers. His workshop in Basel was admired for its clarity of type, thoughtful design, and textual accuracy. The choice to print the Bible in octavo was both a response to market demand and a reflection of his broader ambition: to make the great works of Christianity and antiquity available in formats suited to private study and moral reform.

❧ Hieronymus de Paganinus

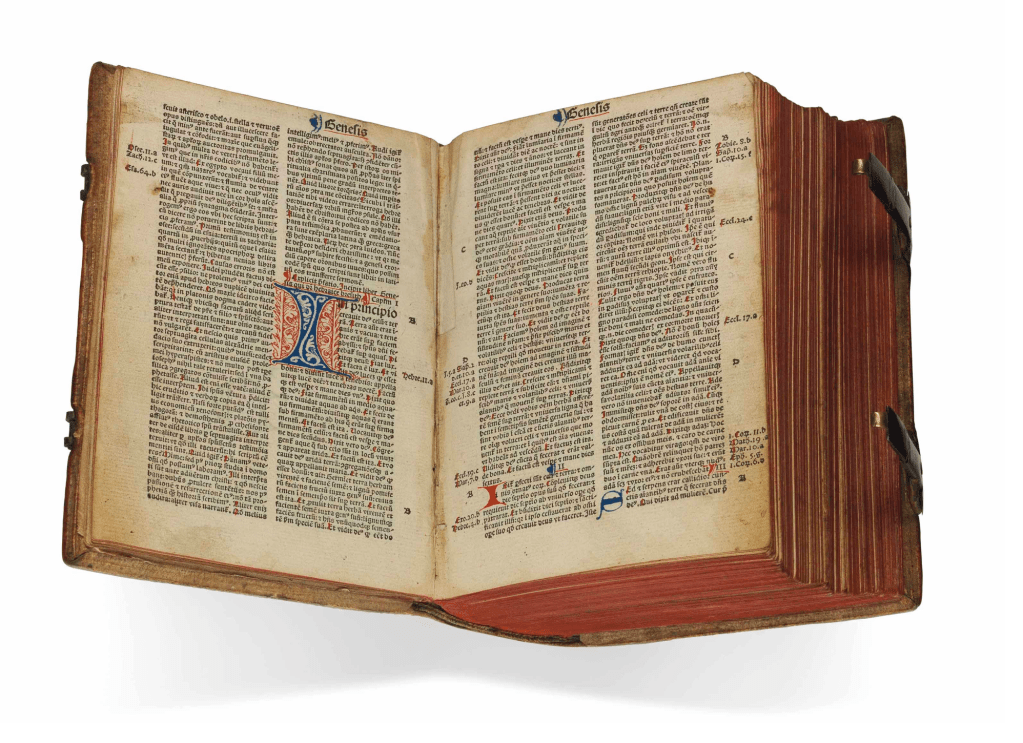

In Venice, Hieronymus de Paganinus operated in a wholly different context. His 1492 octavo Latin Bible, edited by Petrus Angelus de Monte Ulmi, was also compact and complete, but more visually ambitious. It included a title-page woodcut of Saint Peter, the Tabula Alphabetica Historiarum Bibliae by Gabriel Bruno, and the Translatores Biblie—all designed to aid readers in locating and understanding scriptural narratives. Venice, then the undisputed centre of European printing, was a city of commercial saturation, cosmopolitan readership, and fierce competition. Paganinis’s Bible was likely aimed at a clerical and monastic audience, particularly within the Franciscan orbit, but it was also a commercial product crafted for a broader market.

Much less is known about Paganinus than Froben. He did not exist within the same sort of network of prominent humanists, nor did he cultivate the kind of enduring partnerships that defined Froben’s Basel circle. But his publications, including not just his octavo bibles but also editions of legal and pastoral texts, suggest a printer who was alert to clerical needs and aware of the broader European appetite for accessible Scripture. Editions of Gregory the Great, Justinian, and the Breviarium Romanum all point to a market among the religious orders and the learned professions, while vernacular works such as the Leggenda di San Clemente indicate an eye for more popular devotional demand. Thus his octavo bibles might be said to occupy a middle ground: attractive to students and scholars for study, as well as to relatively affluent members of the laity for devotional purposes.

❧ Recapturing the Spirit of the Paris Bible

Despite their differences, both Froben and Paganinus seem to have been reaching for the same ideal: a printed Bible that recaptured the utility and portability of the Paris manuscript tradition. Neither was copying the other; rather, both recognised that the old Paris Bible had been an ideal format—compact, complete, navigable—and that its usefulness had outlasted its physical availability. These octavos were not innovations so much as revivals. Their printing was not the beginning of something wholly new but the restoration of something whose time had returned.

That these editions flourished in two very different cities only strengthens the case for their underlying necessity. Froben’s was shaped by the scholarly currents of northern humanism and spiritual interiority. Paganinis’s arose in a commercial republic teeming with readers, artists, and friars. Basel had theology, Venice had trade; both had readers who needed Scripture in the hand.

The cultural afterlives of these editions also reflect their significance. Savonarola himself owned a copy of Paganinus’s 1492 octavo, now preserved in the Library of Congress, filled with his annotations—especially in the Book of Revelation. Froben’s octavos, though more numerous in surviving copies, have not (yet) been definitively traced to a single famous early reformer. But the demand they met—personal use, practical format, textual clarity—surely included students and clergy who would later become central to the Reformation. It is not hard to imagine Froben’s bibles on the desks of teachers, friars, and young scholars—quietly preparing the ground.

These four octavos deserve a more prominent place in the narrative of biblical and ecclesiastical history. They did more than anticipate reforms that the Church would soon undergo–they also deliberately looked backwards to the models of the thirteenth century. They were commercially successful not because they were fashionable, but because they were useful. In them, we see not just an emergent reformism, but also a spiritual and intellectual continuity extending all the way back to High Middle Ages.