In the first decades of the sixteenth century, the Latin Bible remained an undisputed cornerstone of the European book trade, yet the format and presentation of that Bible were undergoing rapid and sometimes dramatic transformation. By 1509, Jacques Sacon had already established himself as a successful printer in Lyon with two unillustrated folio Latin Bibles to his name. His press was known for its typographical clarity, scholarly apparatus, and reliable execution—features prized by clerics and university men alike. But it was not until 1511, when the Venetian printer Lucantonio Giunta issued his groundbreaking illustrated quarto, that a new visual and editorial standard was set for biblical publication. Giunta’s edition integrated a rich programme of woodcuts with tightly organised marginal apparatus, and although it was produced in a more modest format, its aesthetic and structural influence would reverberate across Europe.

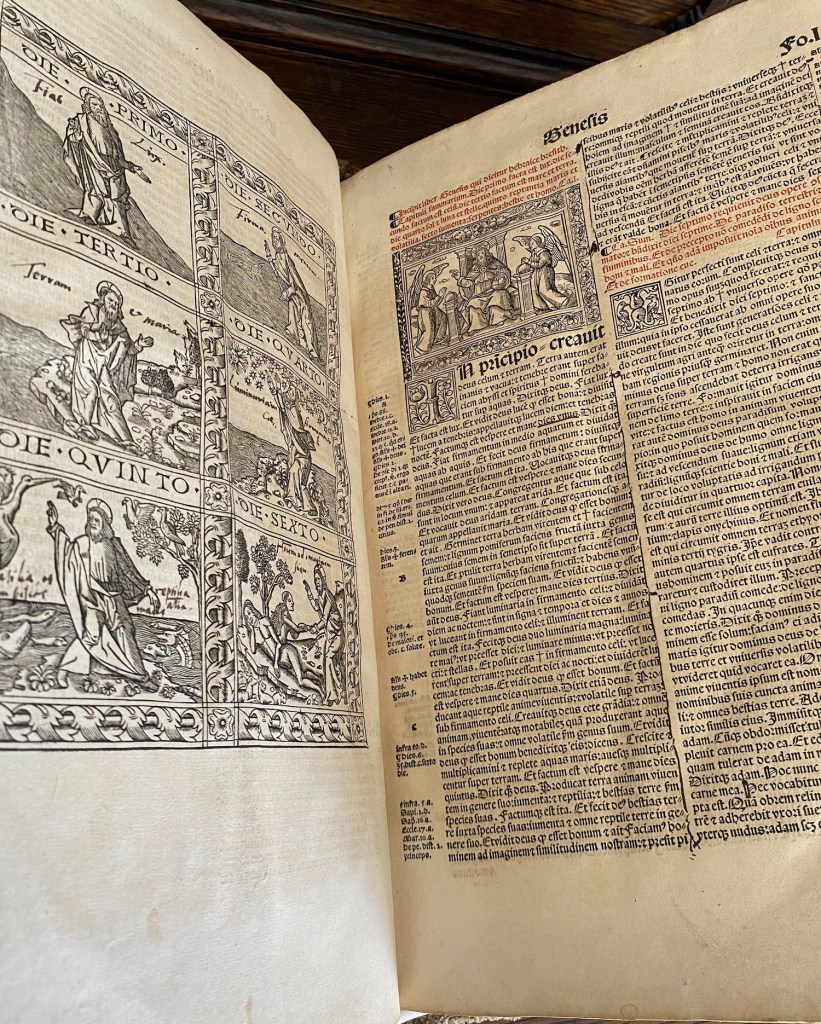

The magnificent opening of the Book of Genesis in the Koberger/Sacon folio Bible (1515).

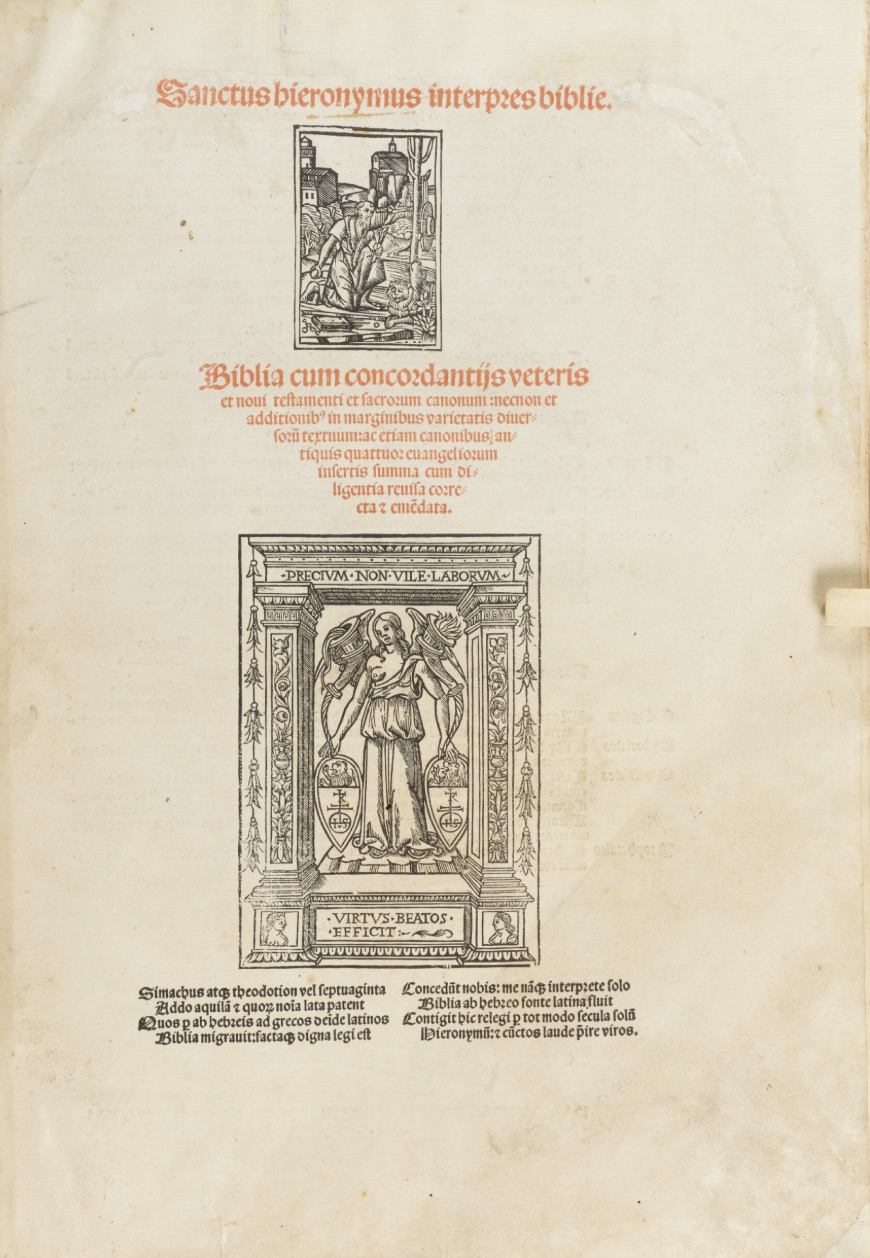

Into this climate of innovation stepped a seemingly unlikely partnership: Sacon, the Lyonnais printer of growing repute, and Anton Koberger, the ageing publishing magnate of Nuremberg, whose own Bible productions stretched back to the 1470s. In fact, Sacon began printing for Koberger several years earlier. Beginning in 1509, they jointly issued about a dozen major scholastic and devotional works, including the sermons of Pelbárt de Temesvár and the Sentences of Peter Lombard, often noting Sacon as printer and Koberger as financier. These editions prepared the ground for a later collaboration that resulted in a remarkable series of eight monumental folio Latin Bibles printed between 1512 and 1522—a decade-long editorial enterprise marked by both continuity and calculated reinvention. The first three editions (1512, 1513, 1515) are effectively identical, a sign that the partnership launched with a stable, proven text and that the initial model was profitable enough to warrant rapid reissues without alteration. But change soon followed. In 1516, a new title page was introduced. In 1519, the final appearance of the original woodcuts gave way to an entirely new illustrative programme, including designs attributed to artists from the Dürer school. Why such investments? Why risk costly commissions after five previous editions had already circulated widely?

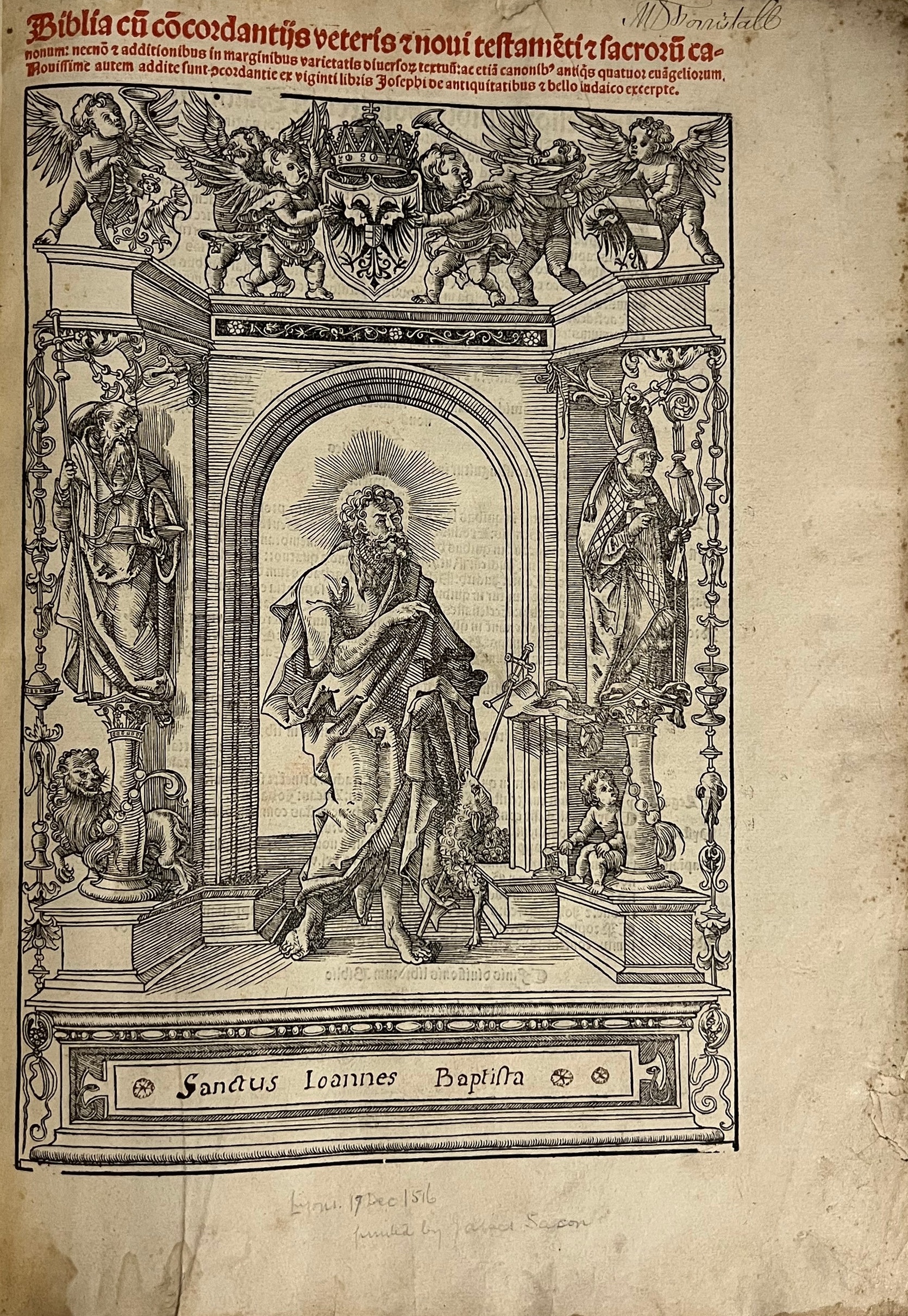

1512 Koberger/Sacon Title (left), 1516 Koberger/Sacon Title (right)

The answer, it seems, lies in both demand and competition. The sheer frequency of publication between 1512 and 1515 suggests that these bibles sold briskly, likely across a broad swath of ecclesiastical and academic buyers in France, the Empire, and perhaps beyond. Each edition reinforced the Bible’s position as a luxury object, a scholarly tool, and a devotional aid. The addition of references to parallel events in Josephus’s Jewish Antiquities and The Jewish War (beginning in 1516) further points to a readership eager for enriched commentary and historical framing. And the investment in new woodcuts in 1519—by which point Koberger himself had died—was not a simple aesthetic refresh. It signalled an arms race of sorts, a bid to maintain visual pre-eminence in a market where others had begun to imitate.

Indeed, the influence of the Sacon-Koberger folios was profound. Etienne Gueynard’s 1520 Biblia Magna—with its elaborate title page—set a new benchmark that was directly copied by Jean Crespin and Jacques Mareschal. Yet Sacon, curiously, did not follow Gueynard’s path. His folios maintained their own design trajectory, reinforcing the sense that these bibles were not just commercial commodities but distinct statements of typographic and theological identity. It is all the more telling, then, that Lucantonio Giunta—whose 1511 quarto had started the whole visual revolution—never produced a folio Bible. His next venture was a single, splendidly illustrated octavo in 1519, unsurpassed in quality, but never reissued. Had Giunta gone to the trouble of printing a folio Latin Bible (he never did), one can only imagine how magnificent it might have been.

What emerges from this landscape is a portrait of early sixteenth-century biblical printing as a dynamic field shaped by competition, artistry, and shifting readerly expectations. The eight Sacon-Koberger folios stand at its centre: not merely a commercial enterprise, but a cultural force that catalysed innovation, imitation, and no small measure of rivalry.

Sacon/Koberger Folios

- 1512 – First Illustrated Edition

Lyon, Jacques Sacon; at the expense of Anton Koberger

– First folio Bible in this series

– Introduced woodcut illustrations based on Lucantonio Giunta’s 1511 Quarto - 1513 – First reprinting of 1512 Edition

Lyon, Jacques Sacon; expensis Anton Koberger

– Maintains structure and woodcuts from 1512 - 1515 – Second reprinting of 1512 Edition

Lyon, Jacques Sacon; expensis Anton Koberger

– Last to use the 1512 title page - 1516 – New Title Page and First Edition with Josephus References

Lyon, Jacques Sacon & Nuremberg, Anton Koberger

– Adds marginal references to Josephus’s Jewish Antiquities and The Jewish War

– Expands scholarly apparatus - 1518 – Last Edition to include Original Woodcuts

Lyon, Jacques Sacon; expensis Anton Koberger

– Continues with the Josephus references

– Final reuse of 1512 woodcut cycle - 1519 – New Woodcut Series Introduced

Lyon, Jacques Sacon; expensis Anton Koberger, 19 October

– Contains entirely new illustrations commissioned for this edition

– Retains other scholarly apparatus - 1521 – First reprinting the of 1519 Edition

Lyon, Jacques Sacon; expensis Anton Koberger

– Retains new woodcut series

– Scholarly apparatus retained - 1522 – Second reprinting of the 1519 Edition and Final Sacon-Koberger Bible

Lyon, Jacques Sacon; expensis Anton Koberger

– Final edition

– Marks the close of a decade-long editorial and artistic programme

NB: Jean Marion printed two illustrated folio Bibles in the same style for Koberger’s heirs in 1520 (19 August, 12 December). Jacques Sacon printed three folios outside of his partnership with Koberger – two before and one after in 1506, 1509, and 1527. Sacon’s three octavo Latin bibles were all printed independently of Anton Koberger (1511, 1515, 1522).